Fun City

by Emma Rebhorn

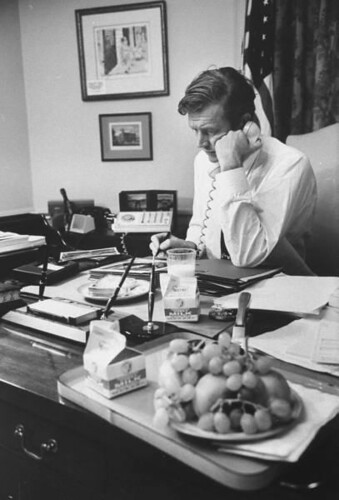

I am nurturing a crush on John Lindsay. He’s dead, he died in 2001, and so it’s a crush a la my really serious feelings for Marlon Brando and Jaffe Ryder. To be honest, it’s a crush reminiscent of my serious feelings for Ryan Gosling: it’s never going to happen.

Lindsay’s liberalism and his pretty face were anathema to Robert Moses, who famously said, “if you elect a matinee-idol mayor, you’re going to have a musical theater administration.” I suspect Mrs. Moses was among the first ones to pine.

Lindsay served as Mayor of New York from 1966 to 1973. He had been the Congressman for the Upper East Side’s “Silk Stocking District” for three terms before that; this was in an age when Democratic machines still stuffed ballot boxes and broke kneecaps. It was courageous, it seems, to be a Republican, and Lindsay was.

The 1960s were a time of shifting boundaries, however, and the dignified party of Theodore Roosevelt was gradually ceding ground to Alabama Governor George Wallace’s police dogs and fire hoses.

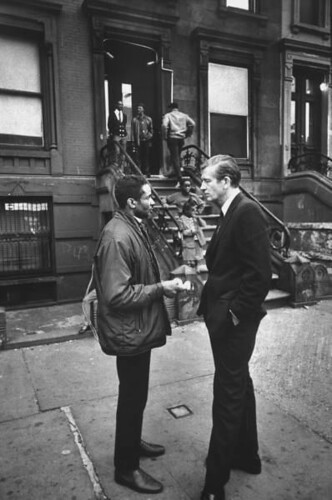

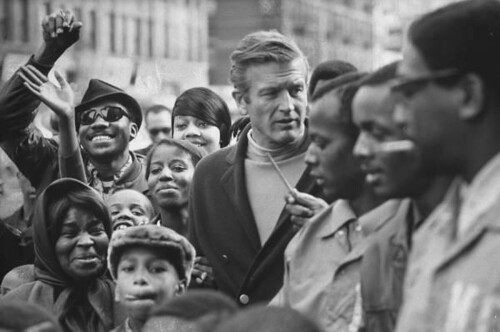

Lindsay treated the streets differently than Wallace. During his first mayoral campaign he spent afternoons walking up and down 145th Street, in Central Harlem. On one of those afternoons he held a town meeting at Covent Avenue Baptist Church and promised the audience “glorious new housing.” I am confident that housing projects had not been called “glorious” before Lindsay, and I am confident that they have not been called so since.

'Glorious' was lofty but Lindsay saw no discrepancy between the majesty of the pulpit and the primal need for shelter. Such a collapsing of the practical into the grand characterized his style of governance, which William F. Buckley, founder of National Review, called “flamboyant idealism.”

The walks continued after the election; Mayor Lindsay’s flânerie expanded to the Bronx and Brooklyn. The New York Times published a sidebar blurb on the excursions in August 1967, confused by its patrician mayor’s sweaty shirts. “All summer long,” the blurb clucks, “he has been patrolling the neighborhoods as if he were a flatfoot in shirtsleeves on the dawn shift.” Lindsay’s security detail was equally befuddled. In 1968, one long-suffering assistant said, “we lost him all the time last summer. He’d disappear into a building and come out all smiles ten minutes later.”

Lindsay’s walking tours carry with them a whiff of voyeurism, a trip to a ghetto zoo. “I feel safer in Harlem than I do at City Hall,” he said, which is something I might have echoed as a shiny faced, starry eyed seventeen year old. Lindsay and the white media presented Harlem residents as blindly loyal to their Mayor: grateful, self-effacing.

In 1968, Lindsay said, “in the areas of the city where I have the greatest protection, it comes from the people themselves—in ghetto communities, in Harlem, Bedford Stuyvesant, and the South Bronx.” The Times continued, incredulous, “Mr. Lindsay said that on his walking tours people on ghetto streets came up to him to say ‘don’t you worry, Mayor, you’re safe here.’”

Such a departure from business as usual frightened the white working and middle classes who had been doing quite well with business as usual. A rift grew between blue-collar civil servants and the increasingly Liberal, well-coiffed Mayor. On one of his walks, Lindsay discovered that the Sanitation Department had been reporting regular cleaning of vacant lots that had not been touched in years.

On Lindsay’s first day in office, the transit workers union went on strike.

Lindsay refused to negotiate with the transit union and the strike lasted for twelve freezing January days. He recommended that commuters stay at home, and asked them not to bring cars into the city. Henry Quill, the brash president of the transit union, made a puckish announcement that, no, in fact, everyone should bring their cars, traffic be dammed. Lindsay was reduced to a childish back and forth and appeared on television the next day, insisting, “Mr. Quill is not Mayor. I am the Mayor. And I’m asking everybody not to bring cars to Manhattan.”

Halfway through the strike, Lindsay walked for four miles in freezing rain from his “headquarters” at the Hotel Roosevelt to City Hall. It probably did not help the Mayor’s effete reputation that City Hall provided apparently insufficient head-quartering, but what really consigned him to mockery during the strike was his announcement following the walk, “I still think New York’s a fun city!”

There was hail and some people hadn’t been able get paid for a week. No one else was having any fun.

When Lindsay ran for re-election as Mayor in 1969 he was defeated in his own party’s primary by the virtually unknown Staten Island State Senator John Marchi. Marchi was, even contemporaneously, acknowledged as utterly personality-less.

Richard Reeves was the Times political reporter. He wrote

There are a multitude of things that Marchi is not. He’s not witty, forceful, passionate; often he is not articulate; he is not truly ambitious. Naturally, he is not recognized; he walks along Broadway on a sunny May day, slightly stooped under the shadows of a dark coat and brown fedora, talking quietly of destroying the political career of John V. Lindsay.

Reeves continues, pointing out that Marchi’s very candidacy was based entirely on his emptiness: “Marchi’s only chance is based on something he is not—he is not Lindsay.” The outer boroughs had spoken in favor of the “not”, but Lindsay went on to win the Mayoral election on the Liberal Party line. The matinee idol and his urban crusaders marched on, idealism and impracticality equally intempered. Years after Lindsay was Mayor, his former city planning commissioner, Gordon Davis, explained, “It was a time when you still thought you could solve the urban crisis.”

The rising popularity of drugs frightened city residents, who tended to exaggerate addicts’ depravity and reject treatment facilities in their neighborhoods. I consider a poem from second volume of Breakthrough, the self-published newsletter of a heroin treatment clinic in Jamaica, Queens, as emblematic of the nihilism of the fraying city. “DL” writes:

Dead babies and broken dolls.

Faust and froth and a mad dog’s jaw.

This is what you mean to me,

All of this and more.

Circus freaks walk alone.

Sticks and stones; broken bones.

A tangled web into I fell,

Sold my soul, a bag of gold.

Nothin beats sweet, sweet hell.

More than half of the country’s heroin addicts were New Yorkers, and the great majority of those lived in the city. Despite widespread local and national opposition, the city’s Health Services Agency dedicated itself wholly to implementing a program of methadone maintenance for heroin addicts. In 1970, when the city’s methadone program was only a year old and serving 2,500 patients, the city Health Commissioner, Gordon Chase, projected that his agency could be serving 15,600 patients within a year. In a memo, he admitted, “the projection of 15,600 addicts is plainly on the optimistic side—and may well be downright unrealistic.” But, he continued unfazed, “it is probably well to set our sights high at the outset. We can always take more than 12 months.” Sure.

When a private methadone treatment facility on the West Side closed due to a sudden decrease in federal funding, the city couldn’t find a adequate replacement. The Health Services Agency decided to rent, for a dollar a year, a decommissioned Staten Island Ferry. After a two-week period of frantic repairs, the Gold Star Ferryboat Clinic opened on June 7, 1971, on Pier One off of Battery Park.

Only months after a mayoral commission called New York City’s subways "the most squalid public environment of the U.S.: dank, dingily lit, fetid, raucous with screeching clatter,” Lindsay had air conditioning installed. This from the man who hadn’t been able to negotiate with municipal school or transit employees and had failed even to get the streets of Queens cleared after an epic 1969 snowstorm.

New York would get worse before it got better: Lindsay declined to run for a third term as Mayor. Voters regressed and elected Abe Beame, an uninspired Democratic machine bureaucrat. The city was virtually bankrupt within three years.

Vincent Cannato’s authoritative and largely negative biography of Lindsay is titled The Ungovernable City. That title is misleading: Cannato argues that it was the Mayor, not the city, which failed. I am not so sure.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, crisis upon crisis plagued American cities. When reminiscing about their time of public service, former Lindsay administration officials frequently invoke the fact that “New York didn’t burn.” It’s true, and cities that did—Newark and Detroit among them—are still scarred. In a time of such tumult, Lindsay’s efforts to unify New Yorkers (members of the Bensonhurst Kiwanis Club, attendees of the Happenings in Central Park, Brooklyn’s Hasidim and Harlem’s Baptists) astounded onlookers simply by virtue of their audacity.

Lindsay died in 2001, poor and dependent on insurance from a pity position to which he’d been nominated by Mayor Giuliani. The core problems of the matinee idol mayor, the flamboyant idealist, were summarized by Lindsay’s former speechwriter Jeff Greenfield: “When we ask Sir Lancelot to feed horses and do the washing, his armor tends to tarnish.”

Emma Rebhorn is a contributor to This Recording. She is a law student living in New Orleans. Her blog is here.

"Ulysses" - Franz Ferdinand (mp3)

"Braveheart Party" - Nas (mp3)

"We're Looking For A Lot of Love (Geese Mix)" - Hot Chip ft. Robert Wyatt (mp3)

"Music is Math" - Boards of Canada (mp3)

"Moment of Clarity" - Jay-Z (mp3)

PREVIOUSLY ON THIS RECORDING

It's important to get tested.

Here too is an orchestra.

It lasts longer and is more consistent.