“A Far Away Feel”: Gram Parsons and the Birds of Creation

by MATTHEW HENRIKSEN

Gram Parsons introduces “Hickory Wind” in the live version that appears on Grievous Angel, recorded only months before his death in 1973, by saying, “Here’s an old song from a long time back.”

A long time back meant 1967, when Parsons first recorded the song with the International Submarine Band. I’m not sure how to measure the last seven years of Parsons' life, from the age of 20 to his death at 26, but time seems mostly irrelevant when I listen to any of the records he’s on.

His voice haunts more than Jeff Buckley’s. His delivery, which is both country and modern with complexities that exceed any of the alt-country stars in his wake, conjures the ghosts of southern music and reckon a place and time Parsons never lived in, while his style resides in the world of post-blues rock and roll, in newly imagined honky tonks in Los Angeles, Chicago and Canada, as well as the tonks in the south.

Emmylou Harris says of their 1973 tour:

We set out to play country music and some rock & roll in the better hippie honky tonks of the nation (some didn’t know they were honky tonks till Gram brought it to their attention).... The crowds were there. The rooms were small, but the energy generated was of a special intensity. It may not have been as audible in Chicago as it was in Austin, but it was always there. And they came to see this young man and to hear the voice that would break and crack but rise pure and beautiful and full with sweetness and pain.

Parsons' lyrics, both those borrowed and his own, speak of the hard times of a naive country boy in the big city:

It’s a hard way to find out

Trouble is real

In a far away city, with a far away feel

But it makes me feel bitter

Each time it begins

Calling me home, hickory wind

He died from an overdose of heroin mixed with morphine from which an ice suppository had partially resurrected him earlier in the day. The overdose had been days if not weeks in making, as the coroner found evident in the build up of toxins in his tissues and organs.

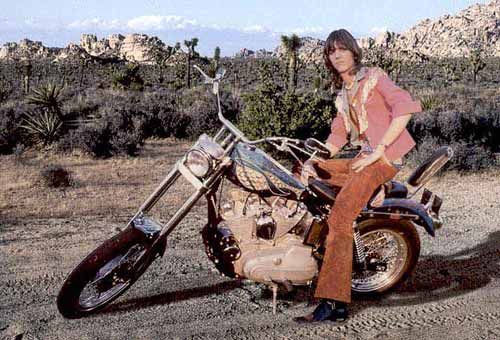

His road manager, who left Parsons' body burning beside a stretch of highway in Joshua Tree National Monument, failed to deliver the divorce papers Parsons had asked him to earlier in the week. The body did not burn to ashes but merely charred, and is now interred along a stretch of highway outside of New Orleans.

I listen to Gram Parsons in Brooklyn; in Fayetteville I read Frank Stanford.

Stanford ended his life at the age of 29 on June 3rd, 1978 (my first birthday) with three shots to the heart from his .22 caliber handgun. On several occasions I have been asked to offer evidence that such a suicide is possible. Stanford left behind thousands of pages of the gorgeous, unsettling poetry, each line as dense as a Kandinsky painting, yet stark and startling in the clarity of its images, which come at you as rapidly as film frames. Nowhere else have I seen the potency of the single line delivered more truly and pervasively than in Frank Stanford’s poems:

While my mother is washing the black socks

Of her religion,

I climb out of the washtub,

Stinking clean like the moon and the suds

In my ass,

The twenty she earned last week in my teeth

My shoes and my pistol wrapped in my pants,

Slip off the back porch

And head down the road, buck naked and brave,

But lonely, because it’s fifteen hours

By bus to the capital

And nobody will know

How it feels to nail down a heart

Black as tarpaper.

—from “Terrorism”

In her introduction to the posthumous re-publishing of Stanford’s 15,283-line poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Say I Love You, C.D. Wright says,

I do not know whether he was drinking steadily or heavily—water or strictly whiskey. I believe he was both dreaded and loved for his intelligence, his beauty, and his pervasive mystery. I believe that the poem anchored him to the world, and that it stood solidly between himself and a much earlier death than he died.

When I lived in Fayetteville, Arkansas, where Stanford studied briefly and settled, I felt his ghost most acutely when I walked the railroad tracks from Dickson Street to my apartment. I always imagined that Stanford walked the same tracks, with cliff faces on both sides revealing the history of the stone civil engineers carved through. I’m not as sure about Parsons, but I am certain Stanford felt an unimaginable loneliness and blessed us with it in his poems.

It is incredibly difficult to explain that my love for Gram Parsons' music and Frank Stanford’s poems has nothing to do with their early (excessively brutal and un-romantic) deaths, but that their creative processes I admire and to an extent try to follow contributed dramatically, though not entirely, to self-destruction. Hard living for some folks implies a lifestyle image, a self-promoting façade, but some folks prefer to live hard, or have to live hard. Hard living is one of the few outlets for people of irrepressible energy. I guess you can say stillness is the only other outlet aside from suicide, but I don’t understand how to be still.

I’m trying to write about my neighborhood in Greenpoint, on the northern tip of Brooklyn. We’re on the very edge, on a tiny peninsula ending at the confluence of the East River and Newtown Creek, which divides the western border between Brooklyn and Queens. Our rooftop overlooks the BQE and a major sanitation plant to the east, condos under construction in Long Island City, Midtown Manhattan to the west, and to the south in Brooklyn mostly old three and four family houses and church steeples.

At night that’s the quiet, bluer side; during the day that’s the side where I watch birds flying.

Our lives and deaths are not as much ours for the making as we’d like or have to think, but in each poem I can fashion an end and a beginning that make sense together and (I hope) makes sense to others. Trying to make sense of how another artist lived and died only confuses me more.

What I am trying to understand about Gram Parsons and Frank Stanford is how their creative acts could not save their lives. I understand the impulse to self-destruct, but even on my worst nights when I see the early morning light I know that creation is grace. Those mornings I don’t want anything to ever end, and that’s when the songs and the poems seem eternal.

Matthew Henriksen co-edits Typo and Cannibal and curates The Burning Chair Readings.

Insomnia

by MATTHEW HENRIKSEN

I had the busted leg of a plastic chair

to pillow a highway sign’s dream.

Once a person on his roof begins to think

about saying fuck you to the particulars,

the only blessing is a stagnant block

in the middle of a dead neighborhood

in a city that has been nowhere since

before you or I were born. And who

and what are we, after words, but

mourners signing a petition at someone’s

grave, for better dreams, better meals, better

orgasms, though most of us would rather just

sleep well more often. Jesus, why must it

be so late, so bright and so early?

"I Can't Dance" - Gram Parsons (mp3)

"Hearts on Fire" - Gram Parsons (mp3)

"Return of the Grievous Angel" - Gram Parsons (mp3)

"How Much I've Lied" - Gram Parsons (mp3)