To Beat Death Down With A Stick, To Take Over

an interview with Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin

by ELAINE SHOWALTER

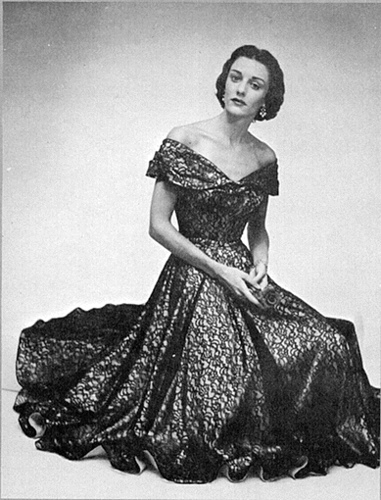

Kumin: Meeting Anne was really fantastic. When I met Annie she was a little flower child, she was the ex-fashion model. She wore very spiky high heels.

Sexton: Well, that was the age.

Kumin: Yes, it was. Well, she was totally chic, and I was sort of more frumpy.

Sexton: You were the most frump of the frumps. You had your little hair in a bun.

Kumin: I was the chief frump. She was really chic and she wore flowers in her hair.

Showalter: Where did you model? I remember reading that, and then it dropped out of your blurbs.

Sexton: It's called the Hart Agency, in Boston.

Kumin: She was a Hart girl. At any rate, we met at the Boston Center for Adult Education where we had each come to study with John Holmes.

Sexton: I came trembling, thinking, oh dear god, with the most ghastly poems. Oh god, were they bad!

Kumin: Well...I don't know if that's true.

Sexton: Oh, oh, Maxine, horrible, horrible. Anyway, your impression of me was — ?'

Kumin: And my impression of Anne was — I don't know what my impression was. I was very taken with her. I think we were each very taken with each other.

Sexton: Now wait a minute. You were scared of me.

Kumin: I was terrified of her, I had just had my closest friend commit suicide, in a postpartum depression. Gassed herself.

Sexton: I wasn't writing about that right off.

Kumin: Now, wait a minute. I'm just saying why I was scared.

Sexton: Why should you know I had anything to do with it?

Kumin: Well, I knew your history.

Sexton: How?

Kumin: You were very open about the fact, of why you had begun to write poetry. You had just gotten out of the mental hospital. And something in me very much wanted to turn aside from this. I didn't want to let myself in for that again, for that separation. And Anne is still very much more flamboyant and open a person than I am. I'm much more closed up, restrained. I think this is certain, although much less so now than then.

Sexton: Can I say? Since your analysis — you're quite a changed person.

Kumin: Yes, since my analysis.

Sexton: I mean, she's gotten attractive and yummy. Before her hair was pulled back and in a bun—

Showalter: I wouldn't have recognized you, Maxine, from your pictures.

Sexton: No pictures are good. She was attractive then, she was attractive then, just a bad picture.

Kumin: The picture on the novel coming out next year is a really good picture of me and my dog. I recommend that picture.

Sexton: She keeps saying, look at my dog. As if the dog were more important.

Kumin: He is kind of spectacular. Anyway, Anne and I met, and we drove into this class together. For a long time, she used to pick me up and —

Sexton: Not at the beginning you didn't. I can remember, it was funny. I remember you going to a reading at Wellesley College and you picking me up. I had on sandals. You said look, she has prehensile toes. I've never forgotten it. And I said, look, anytime you want me to go to reading or anything (because I was desperate then) I'll do anything. And I started to drive Maxine to the Adult Center.

Kumin: And from that we began to go to all sorts of readings together. Actually the reading at Wellesley College was Marianne Moore.

Sexton: Remember her? Because she kept contradicting and saying, now don't handle a line this way, don't do that, that's very bad, you know, and don't end-stop here.

Kumin: She mumbled so. She read so badly. She was a character, in her tricorner hat and her great black robe.

marianne moore & ali

marianne moore & ali

Sexton: Do you remember going to hear Robert Graves? Dear god, he was ghastly!

Kumin: Now, look, we are not here to tell about people who were ghastly readers or we'll be here all night.

Showalter: Was John Holmes in charge of that workshop?

Kumin: Yes, John Holmes was teaching a little workshop, for anybody. It was available to the world, whoever wanted to come. And we would all try our poems. And this, I think, is how Anne and I learned to work by hearing a poem, because we didn't bring copies. John would sit at the head of the table and shuffle through the poems.

Sexton: He didn't do anything alphabetically.

Kumin: And we would all sit there dying, hoping to be chosen.

Sexton: Oh, you'd pray to be chosen.

Showalter: Not afraid to have a poem read?

Sexton: No, not afraid, wanting to be chosen.

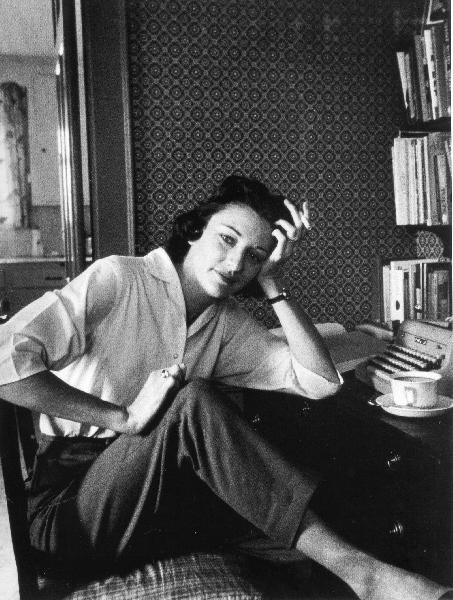

kumin

kumin

Kumin: And he would read your poem, and the class would then discuss it.

Sexton: And he would.

Kumin: And he would.

Sexton: Now we have to go into the fact that as it grew later — well, we used to go out afterwards. John didn't drink.

Kumin: John was a former alcoholic.

Sexton: I don't think I drank myself. I don't think I drank much then, really. I had a beer.

Kumin: But he was really on the wagon. He had been a severe alcoholic. And then after that we broke off from the Boston Center and we formed our own group.

Sexton: But I didn't.

Kumin: You certainly did. When we broke off?

Sexton: I was seeing Robert Lowell.

Kumin: No, that was much later. That was after John was dead.

Sexton: No, wait a minute. I'm very sorry. I was going to Robert Lowell's class, and still John's, without you. Begging for the approval that Daddy would never give. Why was I so masochistic?

Showalter: Was John Holmes a difficult person for a woman to work with?

Sexton: John Holmes didn't approve of a thing about me. He hated my poetry. I remember, even after Maxine had left, and I was still with Holmes, there was a new girl who came in. And he ketp saying, oh, let us see new poems, new poems. We need them. And here I was giving him things that were later anthologized forever. I mean, really good poems.

I remember one night Sam Albert and me going to John's. It was sleeting out, but we make it. And he's on his way out and he's so happy we were going out. I think maybe that moment he forgave me a little.

Kumin: I was then teaching at Tufts, but we all read at Tufts, in the David Steinman series.

Sexton: I never did. No, he wasn't going to ask me.

Kumin: We used to go to parties at John's after all those readings—after John Crowe Ransom, and after Robert Frost. Frost said, don't sit there mumbling in the shadows, come up here closer. By then he was very deaf. And I was so awed.

Showalter: Is the poetry workshopping diminishing too? Do you do this less, need this less, than you used to?

Sexton: No, not as long as we're writing.

Kumin: I think the difference is that perhaps this year haven't been writing as much.

Sexton: I haven't been writing as much either; I've been having an upsetting time.

Kumin: I think the intensity is the same, but the frequency has changed.

Sexton: But just the other day Maxine said, well, that's a therapeutic poem, and I said, for god's sake, forget that. I want to make it a real poem. Then I forced her into helping me make it a real poem, instead of just a kind of therapy for myself. But I remember once a long time ago a poem called "Cripples and Other Stories." I showed it to my psychoanalyst—it was half done—and I threw it in the wastebasket. Very unusual because I usually put them away forever. But this was in the wastebasket. I said, would you by any chance be interested in hat's in the wastebasket? And she said, wait a minute, Anne. You could make a real poem out of that. And you know how different that is from Maxine's voice.

Kumin: I happen to really love that poem.

Sexton: Really? I hate it. Although it's good. It reads well. But we're different temperatures, Maxine and I . I have to be warmer. We can't even be in the same room.

Kumin: I'm always taking my clothes off and Anne is putting on coats and sweaters.

I think that's we're always proud of ourselves that we're not dependent on the relationship. We're very autonomous people, but is a nurturing relationship.

Showalter: What difference would it have made if there had been a women's movement?

Kumin: We would have felt a lot less secretive.

Sexton: Yes, we would have felt legitimate.

Kumin: We both have repressed, kept out of the public eye that we did this.

Sexton: I mean, our husbands, we could have thrown it at them.

Showalter: Why did you feel so ashamed of this mutual support?

Sexton: We did. We were ashamed. We had to keep ourselves separate.

Kumin: We were both struggling for identity.

Sexton: My mother was very destructive. The only person who was very constructive in my life was my great-aunt, and of course she went mad when I was thirteen. IT was probably the trauma of my life that I never got over.

Showalter: How did she go mad?

Kumin: Read "Some Foreign Letters."

Sexton: That doesn't help. Do you know "The Hex"? "Anna Who Was Mad" in Folly? Notice the guilt in them. But the hex is a misnomer. I had tachycardia and I thought it was just psychological.

Showalter: Were you named for her?

Sexton: Yes, we were namesakes. We had songs we would sing together. She cuddled me. I was tall, but I tried to cuddle up. My mother never touched me in my life, except to examine me. So I had bad experiences. But I wondered with this that every summer there was Nana, and she would rub my back for hours. My mother said, women don't touch women like that. And I wondered why I didn't become a lesbian. I kissed a boy and Nana went mad. She called me a whore and everything else.

I think I'm dominating this interview.

Kumin: You are, Anne.

Showalter: Maxine, in The Passions of Uxport, you describe the death of a child from leukemia—a death which has haunted me ever since. Do you think it's more difficult for a woman to write about the death of a child?

Kumin: In all my novels there's a death. In The Abduction there's a sixteen-year-old who dies in a terrible car crash. Perhaps as a mother. I have a fear of a loss of a child.

Sexton: We all know that a child going is the worst suffering.

Kumin: Many years ago, my brother lost a child, and I remember this terrible Spartan funeral. That's the funeral in The Passions of Uxport, when he says the Hebrew prayer for the dead.

Sexton: Do you remember we were young and going to a place called the New England Poetry Club, the first year we won the prizes, first or second. We were terrified. It was our first reading. Maxine's voice was trembling, so we couldn't hear her.

Kumin: I couldn't breathe.

Sexton: I couldn't stand up. I was shaking so. I sat on the table.

Kumin: I wonder if there was a trembling in us—the wicked mother, or the wicked witch, or whatever those ladies were to us.

Showalter: They were all women?

Kumin: There were a few squashy old men.

Sexton: There were young men too. John was there. Sam was there.

Showalter: Did you have trouble with women writer of another generation? In Louise Bogan's Letters—she says about Anne? She doesn't seem to have been able to accept the subjects.

Kumin: This was the problem with a great many people. Women are not supposed to have uteruses, especially in poems.

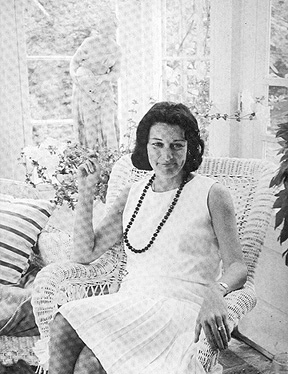

anne sextonSexton: To me, there's nothing that can't be talked about in art. But I hate the way I'm anthologized in women's lib anthologies. They cull out the "hate men" poems, and leave nothing else. They show only one little aspect of me. Naturally there are times I hate men, who wouldn't? But there are times I love them. The feminists are doing themselves a disservice to show just this.

anne sextonSexton: To me, there's nothing that can't be talked about in art. But I hate the way I'm anthologized in women's lib anthologies. They cull out the "hate men" poems, and leave nothing else. They show only one little aspect of me. Naturally there are times I hate men, who wouldn't? But there are times I love them. The feminists are doing themselves a disservice to show just this.

Kumin: They'll get over that.

Sexton: Yes, but by then, they won't be published. Therefore they've lost their chance.

Showalter: When I anthologized you in my book, Women's Liberation and Literature, I chose "Abortion," "Housewife," and "For My Lover on Returning To His Wife." And I like all those poems very much; I'd choose them again.

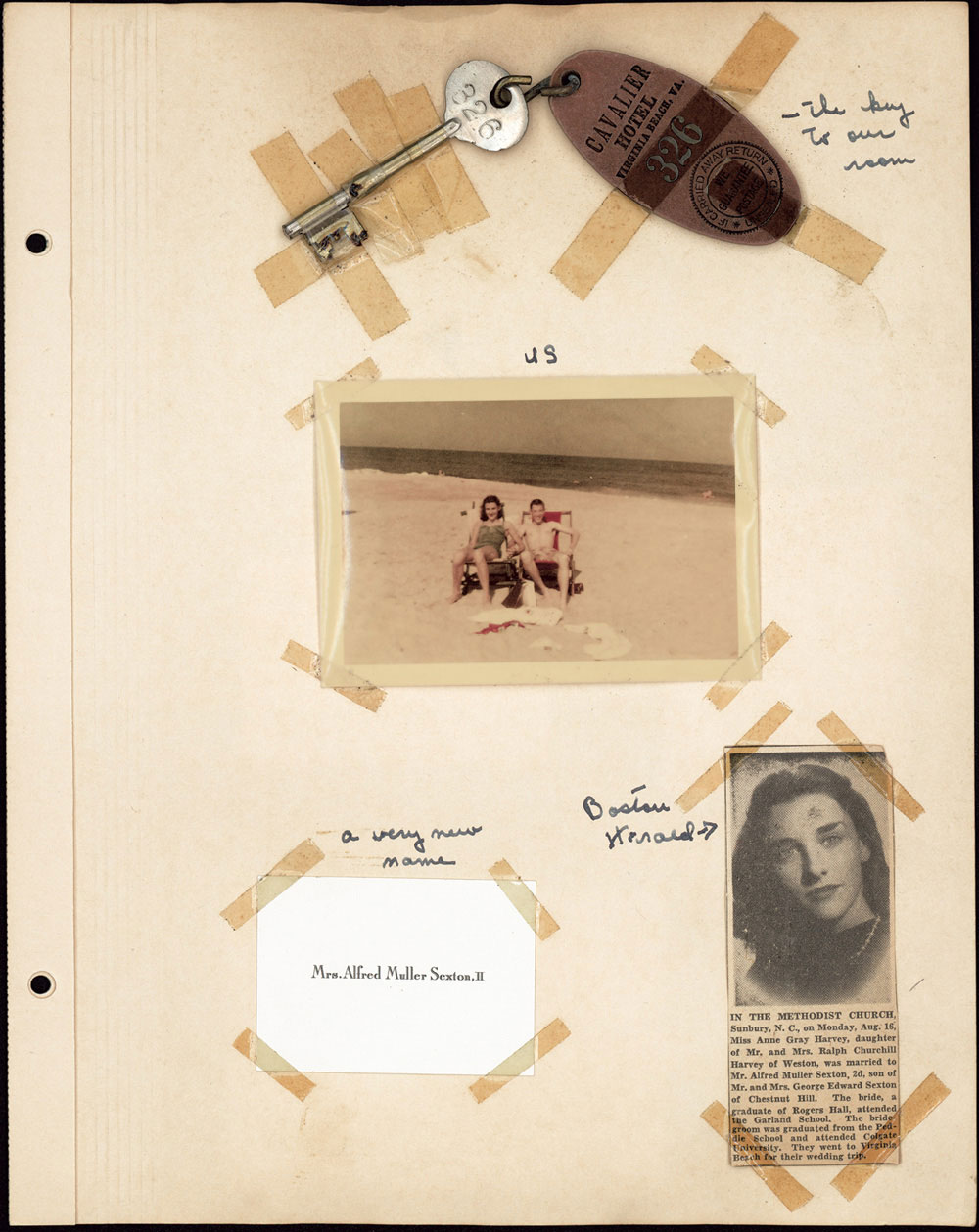

anne's scrapbook

anne's scrapbook

Sexton: "For My Lover" is a help. It doesn't cost very much money to get "Housewife" — you can get it cheap. A strange thing — "a woman is her mother." That's how it ends. A housecleaner—washing herself down, watching the house. It was about my mother-in-law.

Showalter: A woman is her mother-in-law.

1974

"Black Rainbow" - St. Vincent (mp3)

"The Bed" - St. Vincent (mp3)

"The Strangers" - St. Vincent (mp3)