Woody In His Words and Joan's

From Douglas McGrath's feature in Interview magazine:

MCGRATH: But do you take any pleasure at the end, when you look at the finished product?

ALLEN: I do enjoy it, but very briefly. I'm not a person who has any sentimentality about the past. You know, I don't really have any photographs of me with my actors or posters of my films or any of that stuff up in my house. I don't save any of that stuff. I don't read anything about me. When I'm through with a project, yes, I feel, "Hey, this is good. It came out very nicely. I'm very happy," or conversely, "I'm so frustrated. I had such a beautiful idea and I screwed it up every inch of the way." But then we turn the film over to the people who paid for it and they put it out using some kind of voodoo system. They figure, "We'll do this much on advertising, and we'll put it out in 700 theaters during this time of year, because if we put it out after Passover but before graduation ..." They have this real voodoo system that never ever amounts to anything. And I don't want to hear about the film after that. So I give them the film, and then they ask me if I'll do a little promotion for it, and I do as little as possible because ! feel like a person talking about his film does not induce anybody to see it. For me to say, "Well, it was very challenging making a film in Barcelona," or "It was incredible working with two beautiful women such as Penelope and Scarlett on the set everyday ..." You know, it doesn't mean a thing to anybody. Nobody cares. People decide whether or not they are going to see the film based on whatever ineffable system their body uses, whether it's reviews or word of mouth from their friends or the smell of the picture to them. So I do a little promotion out of loyalty to the money people because I don't want to be a mean guy. But I have no interest in the picture. For instance, Vicky Cristina Barcelona is coming out now. I've already finished the picture with Larry David, and I'm working on a script for another new film. So I have no interest in Vicky Cristina Barcelona. If people love the film, then that is delightful. If they don't like it, then ... hmm ... that's tough. They're either completely right in not liking it, or they're quite brilliant and they see flaws in it that I never saw, or they're philistines and they don't get it and I was right. But it's irrelevant because I don't really know or care.

MCGRATH: Was that always true?

ALLEN: It was true after the first couple films. When you go into the business, all your illusions are shattered right away. You find out that great success or failure doesn't change your life in any meaningful way. And then you find out that the reviews of your film — 1,600 reviews from all over America, each one contradicting theother one — don't mean anything to you either. So, finally, you just give up. If you don't have fun doing the film, then the results of the film will never give you any fun. You find that your film wins some kind of award or is much extolled, but nothing happens. Your life is the same. You still get the sniffles, the toothaches, and all that. Nothing meaningful changes in your life. So I gave up on that idea decades ago.

MCGRATH: Did your parents ever tell you what they thought of certain films?

ALLEN: No. They didn't think much. They were just delighted that I was quote-unquote famous. But they couldn't discern between one or the other. They didn't get most of the pictures.

MCGRATH: Did they have a favorite and a least favorite?

ALLEN: No. My mother would like the ones that had strong stories, and my father used to just walk down to the theaters and look at the lines outside.

MCGRATH: That's important, too — especially for parents.

ALLEN: I know. Sean Connery told me the same thing about his father. He said his father used to walk down and look at the lines and come back home and tell him there was a big line at this theater, a big line at that theater. My father did the same thing.

MCGRATH: Do you think your parents contributed to your worldview? Can you point to parts of your personality that can be traced to each of them?

ALLEN: Yeah. I think — and my sister would agree — that I've inherited the worst of each parent. I have my father's hypochondria and lack of concentration. I have his amorality. I have everything bad that he had. Then I have my mother's surly, pill-like, complaining, whining attitude. The only positive thing you could say is that my mother instilled in me--probably at a greater cost than it was worth — an enormous sense of discipline and a feeling that the highest achievement that I'm capable of is not good enough. And so I'm always striving, and that has rebounded to my benefit. I've earned some money doing that, and I've stayed on the straight and narrow for the most part, so that's been a help to me.

MCGRATH: Why? What direction did they lead you in?

ALLEN: I mean, I never read a book until I was 18 years old. I never read a single book. I was a smart kid and I was not understood by my parents.

MCGRATH: Were they encouraging you to be something other than what you were?

ALLEN: They were like all Jewish parents. They hoped that I would be studious enough to become a doctor or a lawyer or some professional thing. They were creatures of the Depression--they would have been thrilled if I had become a pharmacist or something reliable. But I don't think that I've ever fulfilled my promise. I think that I was born lucky with a very good sense of humor and a reasonably good native intelligence. But I should have studied and been bookish. I should have gone to college and become a philosophy major. I should have studied literature. I should have aimed much higher than I aimed. I mean, I was interested in show business and magic tricks and tap-dancing and joke-telling — these were, you know, the trivial, escapist activities of my childhood. I should have been interested in writing novels and serious plays and poetry and things like that. Had I been better directed as a child, those are things that I think would have stood me better in life. I could have utilized whatever natural gifts I had in a more profound and deeper way. Now, I don't know this to be true — it's just something that I think.

MCGRATH: Is there anything good about getting older?

ALLEN: There's nothing good about getting older. Absolutely nothing. The amount of wisdom and experience you gain is negligible compared to what you lose. You do gain a couple of things — a little bittersweet and sour wisdom from your heartbreaks and failures. But what yon lose is so catastrophic in every other way.

MCGRATH: Of all your films, is there one that represents what you think is the best of who you are? It doesn't necessarily have to be the best film you've made.

ALLEN: Well, that sort of changes from day to day with me. There's a small group of my films that I favor over the large majority of them, where I feel like I achieved, you know, something worthwhile on my own terms. There are a few of those films that I'm sort of proud to have done, and I feel that if you were to show them in a festival with Truffaut's films and Antonioni's films and Fellini's films ... they wouldn't be the best films, but they wouldn't be hooted off the screen either. They could certainly serve as the hors d'oeuvres or the warm-ups to the really great films.

MCGRATH: And which of your films are those?

ALLEN: Well, I think The Purple Rose of Cairo is a film like that, and Bullets Over Broadway is one, and Zelig is one, and Husbands and Wives and Match Point [2005]--I probably have six or seven that I feel are respectable pieces of work, where I don't have to run and hide my head in the sand. I don't have a lot of real abysmal failures. I've got some of them, for sure, but I don't have a lot. I've got a lot of B material. And a quantity of F material.

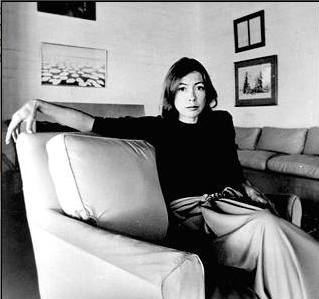

From a 1979 edition of The New York Review of Books...

Letter from 'Manhattan'

by JOAN DIDION

Self-absorption is general, as is self-doubt. In the large coastal cities of the United States this summer many people wanted to be dressed in "real linen," cut by Calvin Klein to wrinkle, which implies real money. In the large coastal cities of the United States this summer many people wanted to be served the perfect vegetable terrine. It was a summer in which only have-nots wanted a cigarette or a vodka-and-tonic or a charcoal-broiled steak. It was a summer in which the more hopeful members of the society wanted roller skates, and stood in line to see Woody Allen's Manhattan, a picture in which, toward the end, the Woody Allen character makes a list of reasons to stay alive. "Groucho Marx" is one reason, and "Willie Mays" is another. The second movement of Mozart's "Jupiter" Symphony. Louis Armstrong's "Potato Head Blues." Flaubert's A Sentimental Education.

This list is modishly eclectic, a trace wry, definitely OK with real linen; and notable, as raisons d'être go, in that every experience it evokes is essentially passive. This list of Woody Allen's is the ultimate consumer report, and the extent to which it has been quoted approvingly suggests a new class in America, a subworld of people rigid with apprehension that they will die wearing the wrong sneaker, naming the wrong symphony, preferring Madame Bovary.

What is arresting about these recent "serious" pictures of Woody Allen's, about Annie Hall and Interiors as well as Manhattan, is not the way they work as pictures but the way they work with audiences. The people who go to see these pictures, who analyze them and write about them and argue the deeper implications in their texts and subtexts, seem to agree that the world onscreen pretty much mirrors the world as they know it. This is interesting, and rather astonishing, since the peculiar and hermetic self-regard in Annie Hall and Interiors and Manhattan would seem nothing with which large numbers of people would want to identify. The characters in these pictures are, at best, trying. They are morose. They have bad manners. They seem to take long walks and go to smart restaurants only to ask one another hard questions. "Are you serious about Tracy?" the Michael Murphy character asks the Woody Allen character in Manhattan. "Are you still hung up on Yale?" the Woody Allen character asks the Diane Keaton character. "I think I'm still in love with Yale," she confesses several scenes later. "You are?" he counters, "or you think you are?"

All of the characters in Woody Allen pictures not only ask these questions but actually answer them, on camera, and then, usually in another restaurant, listen raptly to third-party analyses of their own questions and answers.

"How come you guys got divorced?" they ask each other with real interest, and, on a more rhetorical level, "why are you so hostile," and "why can't you just once in a while consider my needs." ("I'm sick of your needs" is the way Diane Keaton answers this question in Interiors, one of the few lucid moments in the picture.) What does she say, these people ask incessantly, what does she say and what does he say and, finally, inevitably, "what does your analyst say." These people have, on certain subjects, extraordinary attention spans. When Natalie Gittelson of The New York Times Magazine recently asked Woody Allen how his own analysis was going after twenty-two years, he answered this way: "It's very slow…but an hour a day, talking about your emotions, hopes, angers, disappointments, with someone who's trained to evaluate this material—over a period of years, you're bound to get more in touch with feelings than someone who makes no effort."

Well, yes and (apparently) no. Over a period of twenty-two years "you're bound" only to get older, barring nasty surprises. This notion of oneself as a kind of continuing career — something to work at, work on, "make an effort" for and subject to an hour a day of emotional Nautilus training, all in the interests not of attaining grace but of improving one's "relationships" — is fairly recent in the world, at least in the world not inhabited entirely by adolescents. In fact the paradigm for the action in these recent Woody Allen movies is high school. The characters in Manhattan and Annie Hall and Interiors are, with one exception, presented as adults, as sentient men and women in the most productive years of their lives, but their concerns and conversations are those of clever children, "class brains," acting out a yearbook fantasy of adult life. (The one exception is "Tracy," the Mariel Hemingway part in Manhattan, another kind of adolescent fantasy. Tracy actually is a high-school senior, at the Dalton School, and has perfect skin, perfect wisdom, perfect sex, and no visible family.

Tracy's mother and father are covered in a single line: they are said to be in London, finding Tracy an apartment. When Tracy wants to go to JFK she calls a limo. Tracy put me in mind of an American-International Pictures executive who once advised me, by way of pointing out the absence of adult characters in AIP beach movies, that nobody ever paid $3 to see a parent.)

These faux adults of Woody Allen's have dinner at Elaine's, and argue art versus ethics. They share sodas, and wonder "what love is." They have "interesting" occupations, none of which intrudes in any serious way on their dating. Many characters in these pictures "write," usually on tape recorders. In Manhattan, Woody Allen quits his job as a television writer and is later seen dictating an "idea" for a short story, an idea which, I am afraid, is also the "idea" for the picture itself: "People in Manhattan are constantly creating these real unnecessary neurotic problems for themselves that keep them from dealing with more terrifying unsolvable problems about the universe."

In Annie Hall, Diane Keaton sings from time to time, at a place like Reno Sweeney's. In Interiors she seems to be some kind of celebrity poet. In Manhattan she is a magazine writer, and we actually see her typing once, on a novelization, and talking on the telephone to "Harvey," who, given the counterfeit "insider" shine to the dialogue, we are meant to understand is Harvey Shapiro, the editor of The New York Times Book Review. (Similarly, we are meant to know that the "Jack and Anjelica" to whom Paul Simon refers in Annie Hall are Jack Nicholson and Anjelica Huston, and to feel somehow flattered by our inclusion in this little joke on those who fail to get it.) A writer in Interiors is said to be "taking his rage out in critical pieces." "Have you thought any more about having kids?" a wife asks her husband in Manhattan. "I've got to get the O'Neill book finished," the husband answers. "I could talk about my book all night," one character says. "Viking loved my book," another says.

These are not possible constructions, but they reflect exactly the false and desperate knowingness of the smartest kid in the class. "When it comes to relationships with women I'm the winner of the August Strindberg Award," the Woody Allen character tells us in Manhattan; later, in a frequently quoted and admired line, he says, to Diane Keaton, "I've never had a relationship with a woman that lasted longer than the one between Hitler and Eva Braun." These lines are meaningless, and not funny: they are simply "references," the way Harvey and Jack and Anjelica and A Sentimental Education are references, smart talk meant to convey the message that the speaker knows his way around Lit and History, not to mention Show Biz.

In fact the sense of social reality in these pictures is dim in the extreme, and derives more from show business than from anywhere else. The three sisters in Interiors are named, without comment, "Renata," "Joey," and "Flyn." That "Renata," "Joey," and "Flyn" are names from three different parts of town seems not to be a point in the picture, nor does the fact that all the characters, who are presented as overeducated, speak an odd and tortured English. "You implied that a lot," one says. "Political activity is not my interest." "Frederick has finished what I've already told him is his best work by far." The particular cadence here is common among actors but not, I think, in the world outside.

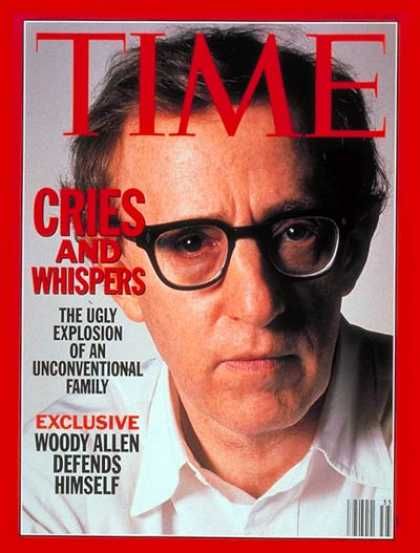

"Overeducation" is something Woody Allen seems to discern more often than the rest of us might. "I know so many people who are well-educated and super-educated," he told an interviewer for Time recently. "Their common problem is that they have no understanding and no wisdom; without that, their education can only take them so far." In other words they have problems with their "relationships," they have failed to "work through" the material of their lives with a trained evaluator, they have yet to perfect the quality of their emotional consumption. Wisdom is hard to find. Happiness takes research. The message that large numbers of people are getting from Manhattan and Interiors and Annie Hall is that this kind of emotional shopping around is the proper business of life's better students, that adolescence can now extend to middle age. Not long ago I shared, for three nights, a hospital room with a young woman named Linda. I was being watched for appendicitis and was captive to Linda's telephone conversations, which were constant. Linda had two problems, only one of which, her "relationship," had her attention. Linda spoke constantly about this relationship, about her "needs," about her "partner," about the "quality of his nurturance," about the "low frequency of his interaction." Linda's other problem, one which tried her patience because it was preventing her from working on her relationship, was acute and unexplained renal failure. "I'm not relating to this just now," she said to her doctor when he tried to discuss continuing dialysis.

"Overeducation" is something Woody Allen seems to discern more often than the rest of us might. "I know so many people who are well-educated and super-educated," he told an interviewer for Time recently. "Their common problem is that they have no understanding and no wisdom; without that, their education can only take them so far." In other words they have problems with their "relationships," they have failed to "work through" the material of their lives with a trained evaluator, they have yet to perfect the quality of their emotional consumption. Wisdom is hard to find. Happiness takes research. The message that large numbers of people are getting from Manhattan and Interiors and Annie Hall is that this kind of emotional shopping around is the proper business of life's better students, that adolescence can now extend to middle age. Not long ago I shared, for three nights, a hospital room with a young woman named Linda. I was being watched for appendicitis and was captive to Linda's telephone conversations, which were constant. Linda had two problems, only one of which, her "relationship," had her attention. Linda spoke constantly about this relationship, about her "needs," about her "partner," about the "quality of his nurturance," about the "low frequency of his interaction." Linda's other problem, one which tried her patience because it was preventing her from working on her relationship, was acute and unexplained renal failure. "I'm not relating to this just now," she said to her doctor when he tried to discuss continuing dialysis.

You could call that "overeducation," or you could call it one more instance of "people constantly creating these real unnecessary neurotic problems for themselves that keep them from dealing with more terrifying unsolvable problems about the universe," or you could call it something else. Woody Allen often tells interviewers that his original title for Annie Hall was "Anhedonia," which is a psychoanalytic term meaning the inability to experience pleasure.

Wanting to call a picture "Anhedonia" is "cute," and implies that the auteur and his audience share a superiority to those jocks who need to ask what it means. Superior people suffer. "My emptiness set in a year ago," Diane Keaton is made to say in Interiors. "What do I care if a handful of my poems are read after I'm dead…is that supposed to be some compensation?" (The notion of compensation for dying is novel.)

Most of us remember very well these secret signals and sighs of adolescence, remember the dramatic apprehension of our own mortality and other "more terrifying unsolvable problems about the universe," but eventually we realize that we are not the first to notice that people die. "Even with all the distractions of my work and my life," Woody Allen was quoted as saying in a cover story (the cover line was "Woody Allen Comes of Age") in Time, "I spend a lot of time face to face with my own mortality." This is actually the first time I have ever heard anyone speak of his own life as a "distraction."

Joan Didion penned this essay in 1979. You can subscribe to The New York Review of Books here. Columbia professor John Romano wrote the letter that follows.

To the Editor:

What piques screenwriter Joan Didion so much about those large, enthusiastic audiences Woody Allen gets is that they seem to recognize themselves in lives that Didion finds unimportant. People who live such lives are unimportant to Didion because they "go to restaurants and ask one another hard questions" about "relationships," something only "adolescents" still discuss much. Evidently where Joan Didion lives problems of love and psyche evaporate in a haze of margaritas by age twenty-one and folks can get down to the real business of living—which is what, by the way, if it isn't the self or others? Losing weight? More likely, it's vocations. Careers. Movie deals.

Didion complains that Woody Allen is stuck in the "fairly recent" notion of finding or making or inhabiting the self, as a central obsession. She's right that it's recent: those who trace it back to Augustine are exaggerating, a little. But surely the literature of "recent" centuries is richer for the works of people who've made this same faux pas. It's what modern narrative art is mostly about, and Didion is sophomoric ("adolescent?") in complaining that Woody Allen hasn't managed to rehabilitate pre-modern modes of being, such as "attaining grace." Didion would make a vice out of the fact that Woody Allen keeps to the side of the street he knows best—the sign of a tyro, by the standards of Hollywood, where a "writer" is someone who can dish out visions of the Gold Rush, the Boxer Rebellion, or the Lower East Side with equal competence. She calls the narrowness of Woody Allen's focus "self-absorption." Another word for it is modesty.

Admittedly there's nothing modest about the list of things he lives for in Manhattan, but that's not what Didion doesn't like about it. Instead she notes that it's "modishly eclectic," which is a too deft way of saying that the list isn't governed by any particular fashion or set of fashions. Here Didion's need to attack the mindlessly modish audience (for roller-skating in crumpled linen, is it?) overcomes her intellectual honesty. The "Jupiter," as she knows, is not at all a stylishly unfamiliar symphony—I think I've heard it in the Park—nor is a passion for "Potato Head Blues" likely to win you fancy friends. Didion may resent Woody Allen's public display of his connoiseurship—and a (gorgeously) indulgent scene it is, too—but she shouldn't pretend she knows his tastes to be modish when she can't, because they ain't. For instance: she says that the point of listing Sentimental Education is to obviate a gauche reference to Madame Bovary. A subtle discrimination, indeed! To know which of these two novels is hipper than the other betrays a suspiciously keen eye for what's in, what's out. Keener than Allen's.

Which brings me to his defense on one last point, and here I'm answering not only Joan Didion, but also my friend Michael Wood, who in these pages [NYR, June 29, 1978] made the point that Allen doesn't know as much as he implies about the bulk of his literary references. Probably there's truth in this; that bulk is rather large. But when an allusion is apt — and even illuminating — it deserves credit even from the knowing. And the concerns of Sentimental Education have an eerie relevance to the concerns of Manhattan. In Frédéric Moreau as in the character Woody is endlessly playing, strength of feeling isn't a source of action but rather an enfeeblement. By reminding us of the barely sympathetic, weak Frédéric, Woody Allen is reinforcing not the central character but those others in the film (or in the audience) who doubt his strength, his maturity, his authenticity. To say that this similarity in the themes of the two works is just accidental might be quite correct, but it would also be an instance of not crediting on the screen what we wouldn't hesitate to find—and maybe praise—in a flawed but intelligent novel.

John Romano

JOAN DIDION REPLIES:

Oh, wow.

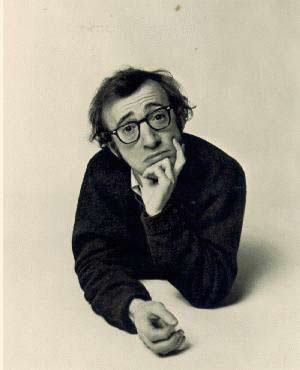

Karina Wolf welcomed us to the man we call Woody. That's him on the left:

Eleanor Morrow took on Melinda and Melinda:

Before Tyler I feel like we didn't really understand Annie Hall...

Jacob Sugarman on Broadway Danny Rose...

Sarah LaBrie handled the intricacies of Match Point...

The multi-talented Yvonne Puig on Crimes and Misdemeanors...

Molly went over a bunch of sequel talk...

Julie Klausner on Hannah and Her Sisters...

Chad Perman on Husbands and Wives...

Woody Allen on his Jewish heritage...

Ben Arfmann on Radio Days...

Marco Sparks on Manhattan Murder Mystery...

Georgia Hardstark on Hannah and Her Sisters...

You can visit the This Recording tumblr here, and the This Recording twitter here.