Sex, Murder, And Insurance Policies

by ELEANOR MORROW

The insurance industry has always been a racket. It's worse than gambling, and you can tell them I said so. In Billy Wilder's masterpiece Double Indemnity, Walter Neff doesn't just sell insurance, he's the best man in the firm. When his erstwhile boss and claims adjuster Keynes asks him if he wouldn't mind getting out of hard-selling people in their homes, he refuses. His business is here, out in the world.

Double Indemnity isn't just an argument against other people, it's the immortal statement of Billy Wilder's genius, bound up in this adaptation of an adaptation based on a true story of a Newark woman who had her husband killed. The overlying metaphor is tough to miss: the insurance business attracts a seedy element. The going-on in a bureaucracy is also dirty gangsterism. The insurance man is inherently dishonest, but he's just doing what we'd all do.

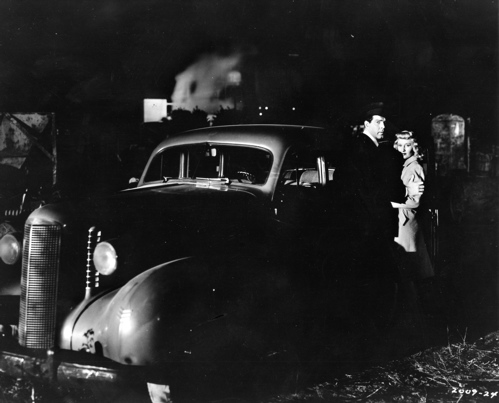

Walter Neff kills Phyllis Dietrichson's husband, a Stanford-educated oil man, to get him to pay off on the insurance policy he signed. He does it for the love of Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck). The film doesn't end well for Neff (played by Fred MacMurray in a particularly blah performance), and the censors demanded an alternate ending that would show Walter Neff in the gas chamber.

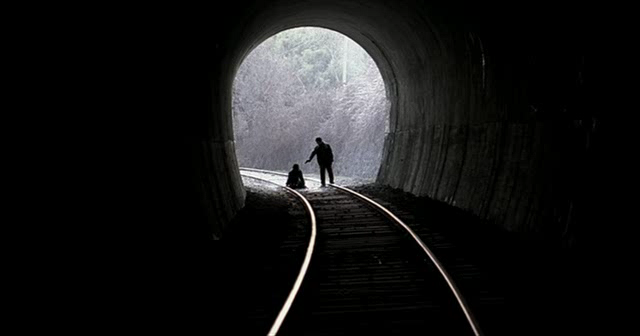

What did he do to deserve such a maudlin fate? He kills Dietrichson on the way to the train station, gets on the train as Dietrichson, jumps off the observation car in the back, and plants the body. It looks like an accident, or at the very least a suicide. Then they collect on the insurance policy they got Mr. Dietrichson, the miserable bastard, to sign before he perished, but not in any train accident.

Of course we see this entire experience through Walter's eyes, and seen that way, his decisions doesn't seem that wrong. His gravelly, matter-of-fact, half delusional voiceover is actually an unreliable narration, a trick that Wilder stole from Orson Welles, or Orson Welles stole from Wilder. It gives the tricksy story infinitely more depth. We cannot know if what Walter is describing really occured, and you can endlessly debate what is real and what isn't to levels of meaning previously discernible only to students of the Talmud.

This innovative point-of-view trick takes Double Indemnity out of the realm of simple noir and into the arena of moral adjudication. What have we learned in this part of life? Yes, it's wrong to kill, but even killers have boundaries. One killer is more of a killer than another killer, wrote Gertrude Stein, probably.

Because of our indifference to Phyllis' attractiveness, we see what Neff doesn't. (Like she is some mad witch, Neff is focused on her anklet when he first meets her: the Horror!) We grow to hate Phyllis, and to sympathize with Walter. After Phyllis' husband's death, Walter even buddies up with her cute stepdaughter, taking her out on a series of several dates after she comes to him with concerns about the murder. It is a haunting scene, but Wilder shows it to us as the deeply disturbed Neff must view it: he doesn't notice that the girl is sitting crying as he's smoking his brains out at the Hollywood Bowl.

Stanwyck really gets the bad end. The evidence points the fact that she doesn't actually have the will to kill anyone. She's just good at staying alive while other people die. We don't see her side of the story, and she disappears from the film for much of its second act. She's rather fatalistic and even gets the best of Neff at the end, before he gets the best of her.

raymond chandler cameo

raymond chandler cameo

Perhaps audiences weren't really ready for a Chandler-like twist in which evil resided solely in the heroine. She's the perfect femme fatale, even more sinister in flowing chiffon. She never does anything but complain about her husband and insinuate that Walter doesn't really love her. We find out from her stepdaughter that she's not exactly unfamiliar with homicide, having murdered her mother as well.

But aren't those the things you'd expect from such a harlot?

Yet he does love her. At one point when he has every reason to turn away from her and the fate she represents, he says, "No baby, I do love you," and he kisses her harder than he needs to. She is the lure of money, she is the taint of corruption, but she also represents the seductive nature of pure freedom, of not living a boxed in life in a singular apartment where a black dude shines your car and every day seems better than the next. Walter's insane heroism is a vow of independence. The violation of freedom's most sacred tenet is the purest expression of the same.

Wrongdoing eats at Walter, yet his best friend and adjuster Keynes knows that he's not a bad person. Bad people don't confess: didn't you know? Double Indemnity is framed by Neff's voice-over, his accounting to Keynes of exactly what he's done. And Keynes, effortlessly portrayed by the masterful Edward G. Robinson, having heard just a bit of it, can discern the whole of the crime.

In some strange sense, Keynes is the protagonist of Double Indemnity. He stands in judgment of Walter, and we must as well. Keynes barely says anything to Walter when he finds out. "You didn't know the culprit was right across from you," Neff moans with a bullet in his shoulder, bleeding out all over the carpet. "No, I didn't," Keynes says. It is good for us, from time to time, to admit we don't know everything.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording. She tumbls here.