Impressionable

by ELENA SCHILDER

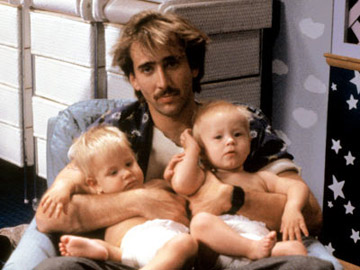

At some point during my impressionable preteen years, my mother and I undertook the time and soul-consuming project of watching Nicolas Cage’s entire filmography. "Filmography" is a word I grew to like, back then, although I am still not sure it’s an accurate or expressive one. Since 1982 (when the world glimpsed him briefly, flipping burgers, behind Judge Reinhold in Fast Times at Ridgemont High), Cage has made sixty movies. Among them are some nearly unwatchable big-budget action movies (Next, Bangkok Dangerous), and some equally unwatchable romantic schlock (City of Angels, The Family Man).

Many of these movies are so bad that one wonders exactly how the film industry has come to value and understand Nicolas Cage: unlike Willis or Stallone, he can’t be expected to get ever manly American ass in seats; likewise, what red-blooded American woman would choose to project her hopes and dreams onto Cage’s growly, disingenuous Family Man?

All of this was, of course, different once. When I asked my mother to try to define Cage’s je ne sais quoi, she didn’t give me a pat quote (it seems that this is impossible when talking about Cage), but she did cite 1983’s Valley Girl as the movie in which he blossomed before her eyes into a mightily irresistible sex object.

Indeed, Valley Girl was Cage’s first real starring role, and it’s worth watching over and over just for the authentically teenage excitements it offers: Nicolas Cage sneaking in through the window of a bathroom at a party he’s been thrown out of, waiting for the girl he’d been flirting with to come in, then watching her apply makeup in the mirror. Valley Girl established Cage as both a rebel and a stud, which is basically what he has stayed – to the extent that the culture has let him.

In 2007, Michael Hirschorn wrote an article for The Atlantic called “Quirked Around” which describes, better than I ever could, the way in which figures like Michael Cera, Wes Anderson and Ira Glass – effete and emphatically quirky men – have proliferated since the 1980s. Hirschorn locates the birth of quirk sometime around 1985, in David Byrne, in Jon Cryer’s character from Pretty in Pink. This is perhaps why Nicolas Cage, in the earlier phases of his career, seemed to make so much more sense than he does now. Cage's quirk reaches further and into stranger corners of the soul than I imagine Ira Glass would feel comfortable with – provided he has one. I’m not really convinced.

Take Moonstruck, a mainstream romantic comedy that nonetheless stars Cage and Cher, two of the more mind-bendingly weird cultural icons of our time. For whatever reason, the 1987 gem manages to combine impassioned quirkiness with a straightforward and heart-warming plot. In an early scene, Cage’s one-handed Italian-American baker, sweating, sweeps Cher (literally) off of her feet, into his bedroom, roaring “SON OF A BITCH!” As always with Cage, there are elements of irony to his performance – edges and intonations that remind us that he’s acting, that he may be intentionally overdoing it. But these strange ironies only make his performance in a movie like Moonstruck that much more pleasurable: as always, there is a light-heartedness to his brooding and a hint of darkness in his happiness.

We often want to classify actors into two camps: Daniel Day-Lewis and Julia Roberts. It’s fashionable to believe that among movie stars there are the really “fine actors” whose work is helped along by crazy Method shenanigans and a healthy dose of self-seriousness, and then there are those who have ridden to fame on the basis of their million-dollar smiles – sex appeal and charm, all the way to the bank. Daniel Day-Lewis is believed to have “range” (does he, though?) whereas Julia Roberts is “always Julia Roberts.”

Nicolas Cage presents an interesting case, in that he has great range, while remaining singularly himself in every role. In watching all of his movies (okay, not all) one is struck by just how much he can do and has done: he channels noir giants like Humphrey Bogart, he carries entire action movies with genuine cowboy swagger (again, with hints of irony, as in 1997’s amazing Con Air), and on more than one occasion he appears as an heir to Jimmy Stewart’s own original brand of quirk, never more so than in 1994’s It Could Happen to You, in which he plays a saintly – yet Cage-y – New York cop.

At some point in the mid-90s, however, it does seem like a certain sickness started to wear away at the vibrant and legitimately sexy quirk we had all come to love in Cage. In 1996 he won an Oscar for Leaving Las Vegas, in which he plays a perpetually gray-faced, doomed alcoholic – a type that he has not been able to leave behind, and which now seems to be at the core of his best work, Sorcerer’s Apprentice aside.

In movies like Adaptation and Bringing Out the Dead, he plays disturbed and/or drug-addled losers – losers in the sense that these men seem utterly lost, vulnerable and perpetually at the precipice of an existential quagmire. The downward spiral has been thorough, so much so that, at moments, when Herzog’s camera finds him in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, Nicolas Cage seems like a skinny, cap-toothed ghost of his former self.

Of course, these sea changes in his career may be attributable to Cage’s own boredom or desire to experiment as an artist. A friend told me that he owned several castles and is under a lot of financial pressure, which is why he continues to make shitty blockbusters. Nonetheless, I think it’s worth considering that we no longer live in an America that appreciates Cage’s sexy ghoulishness. We’ve replaced Cage’s gothic brand of quirk with Michael Cera’s safe, stammering awkwardness and Ira Glass’s geeky self-assurance. And although I know, and acknowledge, that there is a breed of young woman who has now come of age admiring – wanting, even – Michael Cera’s skinny, dispassionate bod, I can’t personally fathom what that might feel like.

Elena Schilder is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in the Netherlands. She blogs here. She last wrote in these pages about Keith Gessen and Elif Batuman.

"You'll Be Always Mine" - The Impressions (mp3)

"Only You" - The Impressions (mp3)

"(Baby) Turn On To Me" - The Impressions (mp3)