Alone In His Wrongness

Time interval is a strange and contradictory manner in the mind. It would be reasonable to suppose that a routine time or an eventless time would seem interminable. It should be so, but it is not. It is the dull eventless times that have no duration whatever. A time splashed with interest, wounded with tragedy, crevassed with joy — that’s the time that seems long in the memory. And this is right when you think about it. Eventlessness has no posts to drape duration on. From nothing to nothing is no time at all.

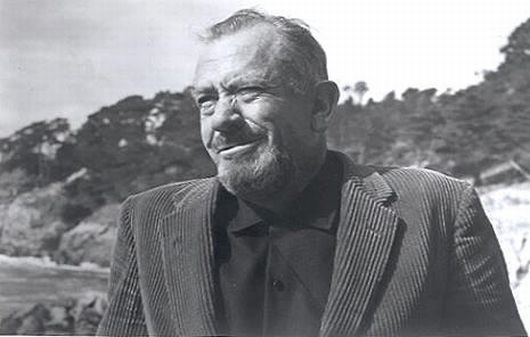

In both his private correspondence and his fiction writing, the prose of John Steinbeck was clear in its minute details but murkier once you stood back to appraise the whole. As the following letters to his friends and agents Mavis McIntosh and Elizabeth Otis prove, John was an exacting and demanding artist who struggled with the impositions that fame placed on his life. These letters take us up to the publication of his novel Cannery Row; his masterpieces The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men had already made him a number of friends and enemies. Above all, they had turned him into what he most resented: a literary phenomenon. The tumult destroyed his first marriage to his wife Carol, and threatened to do the same with his second wife Gwyn in the excerpts that follow.

To Mavis McIntosh

Montrose, January 1933

Dear Miss McIntosh,

We live in the hills back of Los Angeles now and there are few people around. One of our neighbors loaned me three hundred detective magazines, and I have read a large part of them out of pure boredom. They are so utterly lousy that I wonder whether you have tried to peddle that thing I dashed off to any of them. It might mean a few dollars. Could be very much cut to fit, you know. Will you think about it? It would be better than letting it lie around, don't you think?

I think that, when this is sent off (this new novel) I shall do some more short stories. I always think I will and they invariably grow into novels, but I'll try anyway. There are some fine little things that happened in a big sugar mill where I was assistant chief chemist and majordomo of about sixty Mexicans and Yuakis taken from the jails of northern Mexico. There was the Gutierrez family that spent its accumulated money for a Ford and started from Mexico never thinking they might need gasoline. There was the ex-corporal of Mexican cavalry, whose wife had been stolen by a captain and who was training his baby to be a general so he could get even better women. There was the Lazarus who drank factory acid and sat down to die. The lime in his mouth neutralized the acid but he could never go back to his old life because he had been spiritually dead for a moment. His will to live never came back.

There was the Indian who, after a terrific struggle to learn to tell time by a clock, invented a clock of his own that he could understand. There is the saga of the Carriaga family. Son hanged himself for the love of a chippy and was cut down and married the girl. His father aged sixty-five fell in love with the fourteen-year-old girl and tried the same thing, but a door with a spring lock fell shut and he didn't get cut down. There is Ida Laguna who fell violently in love with the image of St. Joseph and stole it from the church and slept with it and they both went to hell. These are a few as they really happened. I could make some little stories of them I think.

I notice that a number of reviewers (what lice they are) complain that I deal particularly in the subnormal and the psychopathic. If said critics would inspect their neighbors within one block, they would find that I deal with the normal and the ordinary.

The manuscript called "Dissonant Symphony" I wish you would withdraw. I looked at it not long ago and I don't want it out. I may rewrite it sometime, but I certainly do not want that mess published under any circumstances, revised or not.

Sincerely,

John Steinbeck

An old friend's backbiting was the genesis of this spirited rebuke.

To George Albee

Los Gatos, 1938

Dear George,

The reason for your suspicion is well founded. This has been a difficult and unpleasant time. There has been nothing good about it. In this time my friends have rallied around, all except you. Every time there has been a possibility of putting a bad construction on anything I have done, you have put such a construction.

Some kind friend has told me about it every time you have stabbed me in the back and that whether I wanted to know it or not. I didn't want to know it really. If such things had been reported as coming from more than one person it would be easy to discount the whole thing but there has been only one source. Now I know that such things grow out of an unhappiness in you and for a long time I was able to reason so and to keep on terms of some kind of amicability. But gradually I found I didn't trust you at all, and when I knew that then I couldn't be around you any more. It became obvious that anything I said or did in your presence or wrote to you would be warped viciously and repeated and then the repetition was repeated to me and the thing was just too damned painful. I tried to sidestep, just to fade out of your picture. But that doesn't work, either.

I'd like to be friends with you, George, but I can't if I have to wear a mail shirt the whole time. I wish to God your unhappiness could find some other outlet. But I can't consider you a friend when out of every contact there comes some intentionally wounding thing. This has been the most difficult time in my life.

I've needed help and trust and the benefit of the doubt, because I've tried to beat the system which destroys every writer, and from you have come only wounds and kicks in the face. And that is the reason and I think you always knew it was the reason.

john

And now if you want to quarrel, it will at least be an honest quarrel and not boudoir pin pricking.

After the stage version of Of Mice and Men received the Critics' Circle award, Steinbeck sent a telegram to the group.

Los Gatos, April 1938

CRITICS CIRCLE, CARE ANNIE LAURIE WILLIAMS 18 EAST 41ST ST NYC

GENTLEMEN: I HAVE ALWAYS CONSIDERED CRITICS AS AUTHORS NATURAL ENEMIES NOW I FEEL VERY MILLENIAL BUT A LITTLE TIMID TO BE LYING DOWN WITH THE LION THIS DISTURBANCE OF THE NATURAL BALANCE MIGHT CAUSE A PLAGUE OF PLAYWRIGHTS I AM HIGHLY HONORED BY YOUR GOOD OPINION BUT MY EGOTISTICAL GRATIFICATION IS RUINED BY A SNEAKING SUSPICION THAT GEORGE KAUFMAN AND THE CAST DESERVE THEM MORE THAN I. I DO HOWEVER TAKE THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THANKING YOU.

JOHN STEINBECK

After Steinbeck submitted The Grapes of Wrath, his editor Pascal Covici wrote to say they loved the book. "It seemed like a kind of sacrilege to suggest revisions in so grand a book," the Romanian Jew wrote, but "we felt we would not be good publishers if we failed to point out to you any weaknesses or faults that struck us. One of these is the ending.

"Your idea is to end the book on a great symbolic note, that life must go on and will go on with a greater love and sympathy and understanding for our fellowmen. Nobody could fail to be moved by the incident of Rose of Sharon giving her breast to the starving man, yet, taken as the finale of such a book with all its vastness and surge, it struck us on reflection as being all too abrupt. It seems to us that the last few pages need building up. The incident needs leading up to, so that the meeting with the starving man is not so much an accident or a chance encounter, but more an integral part of the saga."

In a postscript, Covici added, "Marshall has just called my attention to the fact that de maupassant in one of his short stories 'Mid-Summer Idyll' has a woman give her breast to a starving man in a railway train. Is it important?"

Steinbeck wrote back with the following volley:

To Pascal Covici

Los Gatos, January 16, 1939

Dear Pat:

I have your letter today. And I am sorry but I cannot change that ending. It is casual — there is no fruity climax, it is not more important than any other part of the book — if there is a symbol, it is a survival symbol not a love symbol, it must be an accident, it must be a stranger, and it must be quick. To build this stranger into the structure of the book would be to warp the whole meaning of the book. The fact that the Joads don't know him, don't care about him, have no ties to him — that is the emphasis. The giving of the breast has no more sentiment than the giving of a piece of bread.

I'm sorry if that doesn't get over. It will maybe. I've been on this design and balance for a long time and I think I know how I want it. And if I'm wrong, I'm alone in my wrongness. As for the Maupassant story, I've never read it but I can't see that it makes much difference. There are no new stories and I wouldn't like them if there were. The incident of the earth mother feeding by the breast is older than literature. You know that I have never been touchy about changes, but I have too many thousands of hours on this book, every incident has been too carefully chosen and its weight judged and fitted. The balance is there. One other thing — I am not writing a satisfying story. I've done my damnedest to rip a reader's nerves to rags, I don't want him satisfied.

And still one more thing — I tried to write this book the way lives are being lived not the way books are written.

This letter sounds angry. I don't mean it to be. I know that books lead to a strong deep climax. This one doesn't except by implication and the reader must bring the implication to it. If he doesn't, it wasn't a book for him to read. Throughout I've tried to make the reader participate in the actuality, what he takes from it will be scaled entirely on his own depth or hollowness. There are five layers in this book, a reader will find as many as he can and he won't find more than he has in himself.

I seem to be getting well slowly. The pain is going away. Nerves still pretty tattered but rest will stop that before too long. I fret pretty much at having to stay in bed. Guess I was pretty close to a collapse when I finally went to bed. I feel the result of it now.

Love to you all,

John

Steinbeck's attitude towards his notoriety was particularly troubled because he was an incredibly sensitive person. Any misrepresentation of his work drew out his ire, and he struggled to tune out the noise.

To Elizabeth Otis

Los Gatos, June 22, 1939

Dear Elizabeth:

This whole thing is getting me down and I don't know what to do about it. The telephone never stops ringing, telegrams all the time, fifty to seventy-five letters a day all wanting something. People who won't take no for an answer sending books to be signed. I don't know what to do. Would you mind phoning Viking and telling them not to forward any more letters but to send them to your office? I'll willingly pay for the work to be done but even to handle part of the letters now would take a full time secretary and I will not get one if it is the last thing I do. Something has to be worked out or I am finished writing. I went south to work and I came back to find Carol just about hysterical. She had just been pushed beyond endurance. There is one possibility and that is that I go out of the country. I thought this thing would die down but it is only getting worse day by day.

I hope to be home for about five weeks now but I doubt it. I brought Solow and Milestone home with me and we are working on a final script of Mice and it sounds very good to me.

About the Digest thing, I really would be happier if it weren't done. I don't like digests. If I could have written it shorter I would have, and even a chunk wouldn't be good particularly since Pat refused to give material to anybody else but Saturday Review of Literature and thereby made a hell of a lot of people mad at me.

I saw Johnson in Hollywood and he is going well and apparently they intend to make the picture straight, at least so far, and they sent a producer into the field with Tom Collins and he got sick at what he saw and they offered Tom a job as technical assistant which is swell because he'll howl his head off if they get out of hand.

See you all soon, I hope.

Love,

John

His paranoia intensified in later years. He wrote to a friend: "Let me tell you a story. When The Grapes of Wrath got loose, a lot of people were pretty mad at me. The undersheriff of Santa Clara County was a friend of mine and he told me as follows — 'Don't you go into any hotel room alone. Keep records of every minute and when you are off the ranch travel with one or two friends but particularly, don't stay in a hotel and a dame will come in, tear off her clothes, scratch her face and scream and you try to talk yourself out of that one. They won't touch your book but there's easier ways."

To Carlton A. Sheffield

Los Gatos, November 13, 1939

Dear Dook:

It's pretty early in the morning. I got up to milk the cow.

I'm finishing off a complete revolution. It's amazing how every one piled in to regiment me, to make a symbol of me, to regulate my life and work. I've just tossed the whole thing overboard. I never let anyone interfere before and I can't see why I should now. This ultimate freedom receded. I'm keeping more of it than I need or even want, like a reservoir. The two most important, I suppose — at least they seem so to me — are freedom from respectability and most important — freedom from the necessity of being consistent. Lack of those two can really tie you down. Of course all this publicity has been bad if I tried to move about but here on the ranch it has no emphasis. People up here — the few we see — don't read much and don't remember what they read, and my projected work is not likely to create any hysteria.

It's funny, Dook. I know what in a vague way this work is about. I mean I know its tone and texture and to an extent its field and I find that I have no education. I have to go back to school in a way. I'm completely without mathematics and I have to learn something about abstract mathematics. I have some biology but must have much more and the twins biophysics and bio-chemistry are closed to me. So I have to go back and start over. I bought half the stock in Ed's lab which gives me equipment, a teacher, a library to work in.

I'm going on about myself but in a sense it's more than me — it's you and everyone else. The world is sick now. There are things in the tide pools easier to understand than Stalinist, Hitlerite, Democrat, capitalist confusion and voodoo. So I'm going to those things which are relatively more lasting to find a new basic picture. I have too a conviction that the new world is growing under the old, the way a new finger nail grows under a bruised one. I think all the economists and sociologists will be surprised one day to find that they did not foresee or understand it. Just as the politicos of Rome could not have foreseen that the socio-political-ethical world for two thousand years would grow out of the metaphysical gropings of a few quiet poets. I think the same thing is happening now. Communist, Fascist, Democrat may find that the real origin of the future lies on the microscope plates of obscure young men, who, puzzled with order and disorder in quantum and neutron, build gradually a picture which will seep down until it is the fibre of the future.

The point of all this is that I must make a new start. I've worked the novel — I know it as far as I can take it. I never did think much of it — a clumsy vehicle at best. And I don't know the form of the new but I know there is a new which will be adequate and shaped by the new thinking. Anyway, there is a picture of my confusion. How is yours?

There is so much confusion now — emotional hysteria which passes for thought and blind faith which passes for analysis.

I suspect you are ready for a change. How would you escape the general picture? We're catching the waves of nerves from Europe and making a few of our own.

Write when you can.

John

After finalizing his divorce from his wife Carol, Steinbeck married Gwyndolyn Conger. Eventually they had two children together, Thom in 1944 and John in 1946. He wrote to her often during the forties, especially during his time as a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune.

July 6 1943

Darling, you want to know what I want of you. Many things of course but chiefly these. I want you to keep this thing we have inviolate and waiting — the person who is neither I nor you but us. It's a hard thing this separation but it is one of the millions of separations at home and many more millions here. It is one hunger in a great starvation but because it is ours it overshadows all the rest, if we let it. But keep waiting and don't let it be hurt by anything because it is the one really precious thing we have. Later we may have others but so far it is a single unit — and you have the keeping of it for a little while. You say I am busy, as though that wiped out my end, but it doesn't. You can be just as homesick and lost when you are busy. I love you beyond words, beyond containing. Remember that always when the distance seems so great and the time so long. It will not be so long, my dear.

July 12 1943

My darling.

I wish I could go with this letter. To see you and to hold you would be so good. I know it will seem a very short time when it is over but now it seems interminable like an illness. I have small magic that I practice. When I go to bed, I build up what you look like and how you speak and some times I can almost feel you curling around my back and your breath on my neck. And sometimes it is so real that I am shocked it isn't so. It is raining today and coming onto the time when it will rain nearly all the time. And this morning which is Monday it fills me with gloom. I'm writing the gloom out on you and am loving it. This letter seems much closer than the others.

I love you very deeply and completely — that goes through everything and in everything. Every day I hope I will hear from you at night I haven't. Maybe today. Some of the mail must come through. Perhaps they have held it up, needing the space. I don't know.

Good bye my darling wife. Keep writing.

I love you.

August 19 1943

I wonder what this being apart has done for us. To you, for instance, has it made you think our thing was good or do you suspect it? It has made me think it is exceptionally good and desirable. You said in one letter that you would probably have changed your whole way of life. I hope not so radically that we cannot get back to the good thing it seemed to me. The good nights with the fire going. This winter I must have the little fairy stove connected so that when we go to bed the coals can be glowing. I wonder whether you found a maid at all. I think you will agree with me from now on that we need one. I hate to wash dishes and always will. And I don't like to sleep and all stuff like that. But we will try to get someone who comes in for the day rather than an in-sleeper, that is of course as long as we have an apartment.

Goodbye my darling. I would give something very large to be able to hear from you, but I don't know any way to accomplish it.

Keep good and patient for just a little while now.

To Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation

January 10, 1944

Dear Sirs:

I have just seen the film Lifeboat, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and billed as written by me. While in many ways the film is excellent there are one or two complaints I would like to make. While it is certainly true that I wrote a script for Lifeboat, it is not true that in that script as in the film there were any slurs against organized labor nor was there a stock comedy Negro. On the contrary there was an intelligent and thoughtful seaman who knew realistically what he was about. And instead of the usual colored travesty of the half comic and half pathetic Negro there was a Negro of dignity, purpose and personality. Since this film occurs over my name, it is painful to me that these strange sly obliquities should be ascribed to me.

John Steinbeck

A telegram from Steinbeck in Mexico City from the next month:

PLEASE CONVEY THE FOLLOWING TO 20TH CENTURY FOX IN VIEW OF THE FACT THAT MY SCRIPT FOR THE PICTURE LIFE BOAT WAS DISTORTED IN PRODUCTION SO THAT ITS LINE AND INTENTION HAS BEEN CHANGED AND BECAUSE THE PICTURE SEEMS TO ME TO BE DANGEROUS TO THE AMERICAN WAR EFFORT I REQUEST MY NAME BE REMOVED FROM ANY CONNECTION WITH ANY SHOWING OF THIS FILM

JOHN STEINBECK

In another letter, he wrote "It does not seem right that knowing the effect of the picture on many people, the studio still lets it go. as for Hitchcock, I think his reasons are very simple. I. He has been doing stories of international spies and master minds for so long that it has become a habit. And second, he is one of those incredible English middle class snobs who really and truly despise working people. As you know, there were other things that bothered me — technical things. I know that one man can't row a boat of that size and in my story, no one touched an oar except to steer."

with thom and gwyn

with thom and gwyn

To Bo Beskow

New York

August 16, 1948

Dear Bo:

After over four years of bitter unhappiness, Gwyn has decided that she wants a divorce, so that is that. It is an old story of female frustration. She wants something I can't give her so she must go on looking. And maybe she will never find out that no one can give it to her. But that is her business now. She has cut me off completely. She feels much relieved that she has done it and may even be a good friend to me. She will take the children, at least for the time being. And I will go back to Monterey to try to get rested and to get the smell of my own country again. She did one kind thing. She killed my love of her with little cruelties so there is not much shock in all of this. And I will come back. I'm pretty sure I have some material left. But I have to rest like an old dog fox panting beside a stream. I have great sadness but no anger. In Pacific Grove I have the little cottage my father built and I will live and work in it for a while. Maybe I'll come to see you next winter and we'll "sing sad stories of the death of kings" — with herring.

This is the first of a two part series featuring the letters of John Steinbeck. You can purchase the letters of John Steinbeck here.

"Must Fight Current" - Deerhoof (mp3)

"Secret Mobilization" - Deerhoof (mp3)

"Hey I Can" - Deerhoof (mp3)

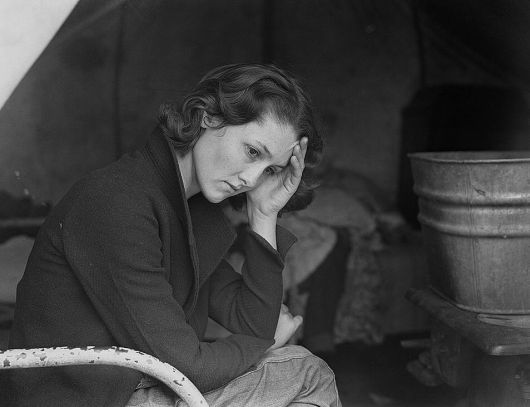

Daughter of migrant Tennessee coal miner, 1936 by Dorothea Lange

Daughter of migrant Tennessee coal miner, 1936 by Dorothea Lange