Insolent Love

by ALEX CARNEVALE

Use your ego as much as possible for creative efforts because though love is mostly ego, much more than it is sex, right now you are frustrated egotistically in the love direction, so you have to find some substitute. It will not make you any happier, for sublimation is not possible, but it will count in the future.

— Fairfield Porter, letter to Larry Rivers

This past summer, the Michael Rosenfeld gallery exhibited a few of Fairfield Porter's paintings of places surrounding his family's summer home in Great Spruce Head, Maine. It was a little underwhelming. For I have always thought that beneath Porter's ostensibly placid paintings lurks something more, evidence of his greatness in the form, if you know the right places to look. Although literature is often easy to enjoy without knowledge of its author, visual art is a different story, and Porter lived passionately in an interesting time and place.

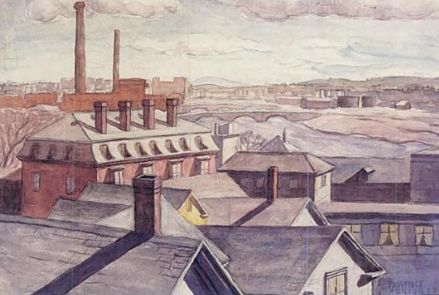

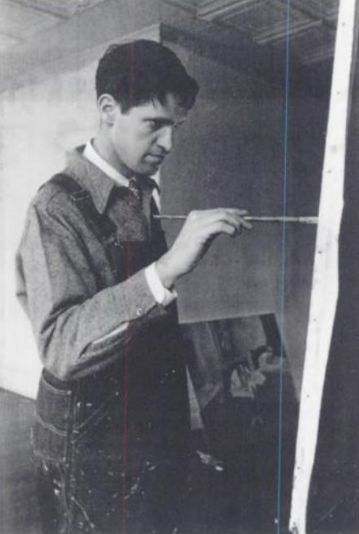

The Roofs of Cambridge, 1927

He was born to a great American family in 1907. Despite the fact that half of Harvard was related to him by blood, Porter ignored his studies during his years there. He resented the introductory art class that allowed him to move on in the field, complaining to his mother that the course "was all theory about colors and so forth and we do silly little painting exercises like making circles of gray, red and blue, etc, varying in value and intensity. And I had to buy $16 worth of apparatus for even that."

with his mother in 1910

That he was failed by our country's educational system doesn't make Porter an iconoclast. Most genuises do terribly in American schools, no matter their background. Nevertheless, he continued his art history education, and near the end of his time at the school decided to become a painter.

Later he reflected on that decision, saying, "When I decided to study art, art was considered of peripheral importance; the artist or poet was thought to be outside of the mainstream of life. I remember a neighbor whom I respected very much, who was disturbed by my decision, and told me so. This man was a businessman, and at the same time an inventor and a poet. He told me that his first reaction to anyone's wanting to be an artist was the thought that this meant deciding in favor of triviality. Then he thought of the Vatican Torso, the piece of antique sculpture which Michelangelo said was his master. Triviality meant to him decorative objects."

After school, Porter immediately went to Greenwich Village. He met many influential figures in the art world, but soon grew tired of so many poseurs. Coming from a distinguished, upper-class family, he had no need to limit himself to pretending that's all he was. Fairfield was also shy. The woman who was to become his wife described first meeting her future husband:

I liked him. He was very simple and direct. Very unaffected. Most Harvard boys talked about how many beers they could hold; Fairfield and I talked about Dostoyevsky. I remember he had a penknife and he was using it on the table, working at it, trying to make the table fall apart. I remember I got on the other end to see if I could do the same. Not to be destructive, just to see if it was possible to make the picnic table fall apart.

Anne Channing also came to be disgusted by higher education, in her case, life at Bryn Mawr. She transferred to Radcliffe and finished her studies there near her parents' Wareham home.

Meanwhile, Fairfield explored the edges of his sexuality on an extended trip through Europe. He always considered himself bisexual, and many of his later friends would be homosexual poets. His first emotional love relationship with a man was with the athletic, fit Oxford student Arthur Giardelli. Much later, he wrote Giardelli reflecting on their time together in Florence:

I think of you very often. You meant a great deal to me, and it means much to me that you remember and write. I don't think that I will write more now. I would like to, but I have lost the sense of who and what you are, and any letter in such a case is like a message in a bottle. You get it — but who are you — now — and did I ever know who you were? Does one ever know another person?

And the doubt must be greater when there is such an inarticulate intimacy as we had; we were shy with each other. I think our importance to each other came from something each of us had to give in the way of support that the other needed and had not really found before. For instance I, as an American, had no interest whatsoever in the social concerns you could not avoid as a poor boy, a scholarship student at Oxford, where as you told me your grandparents' humble origin would have made a curiosity of you if your friends knew it. And what you gave me was something equal and opposite; if you had been an American I would have been afraid of you and considered you beyond me because of your good looks and ordinary athletic abilities. I hadn't such a friend as you at home; but suddenly I had one in Florence, the unattainable became simple. For this I am always grateful. These things count, I hope you know, and I hope what I say will not seem strange to you. I loved you, and I think you loved me.

For Porter to write of this experience endured in his youth again in 1957, says that a part of him never really changed. And, indeed, Porter's combination of callousness and concern for others lasted throughout his life. He hated small talk, and received much from his intellectual equals, including the woman who would become his lifetime companion.

During his travels through Europe, Porter continued to write to Anne. He fell in love with her through her letters, and perhaps his experience with Giardelli helped in allowing him to truly empathize with another for the first time; especially one outside his social class. He was also coming into his own. A young painter named Frank Rogers recalled a chance remark of Porter's made on the high speed train: "Don't you sometimes feel that you're just wonderful? I do. Sometimes I'm so wonderful I want to tell everyone; they ought to know it. It isn't right that they don't."

In May of 1932 Porter returned to New York. He attempted to feel closer to Anne, but soon after they spent a few weeks together he told her "we aren't clicking at all." Nevertheless he proposed to her later that summer at his family's compound, in a rather annoying way. Anne recalled him asking, "Do you think if we got engaged they'd let you stay all summer?" As they pulled away from their September wedding, the car stalled.

Porter's artistic career began in earnest soon afterwards. It was the middle of the Depression, a fact that kept down their rent and buyers away from Fairfield's early paintings. Anne suffered a miscarriage, and was surprised at how little sympathy her husband showed her. Eventually the Porters found they were happier, for a time with Anne in New England, and Fairfield freer to express himself sexually and artistically in New York.

A young Trotskyite, Porter affiliated himself with various associations of artists, but when he was not in the studio, he tried to instruct himself in painting by copying the classics in the Met. Two years after their wedding, Anne had a child, John, and Fairfield was a father for the first time. Although Porter was initially attached to the child, the boy's sickness involved excessive crying, and it drove him out of the house, into various leftist political causes. Among his friends, Fairfield was a rarity — married with child while other bohemians constantly fucked around. The young family moved to the Chicago suburb of Winnetka because of their son's health situation, which would torment the family throughout his schizophrenic adolescence, and even after that.

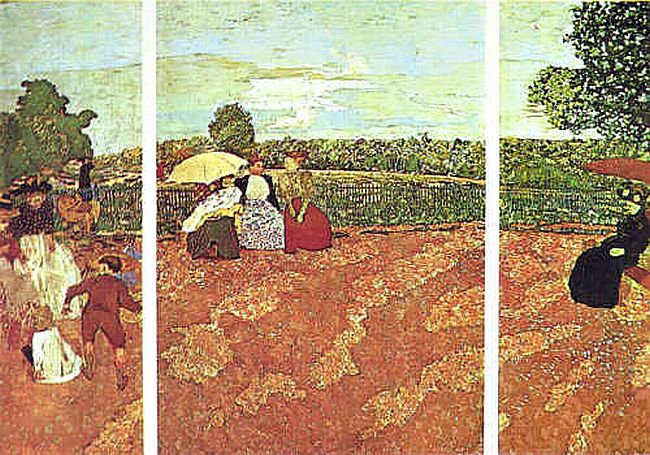

Porter's first artistic successes came about primarily because of his mother Ruth's influence. His early work in political murals had started to give way to watercolor, however, and his development reached a turning point when he saw the work of Edouard Vuillard.

A 1938 exhibition of Bonnard and Vuillard had a tremendous effect on Fairfield. Porter later told Paul Cummings that "I looked at the Vuillards and thought...Why does one think of doing anything else when it's so natural to do this? ... When Bill was first influenced, you know, by modern art, it was Picasso he was emulating. With me it was Vuillard."

In Justin Spring's fascinating biography of Porter, he describes how the artist also felt a similar kinship with the work of Pierre Bonnard: "They say it's too nice. What do they meant by that? They mean it's too pretty. They might mean it's saccharine. They might also mean that they can't approve of the emotion it gives them." Porter's paintings began to focus on bringing out that same kind of emotion.

In 1940 the Porters returned to New York, now with two children in tow. Anne had thought herself unable to conceive again as a result of Malta Fever, but she became pregnant again. Fairfield was less than pleased by this development, finding the responsibility of the children interfered with his work. Then Porter met the beautiful, flirtatious Ilse Hamm. Hamm was a younger, more exciting version of his wife — they even looked alike. Porter never entered in serious romantic congress with Hamm, but nevertheless told his wife he loved her. (Anne was pregnant at the time with their son.) Hamm enjoyed Porter's attentions, but had no desire to sleep with him.

Fairfield's relationship with Hamm was a precursor to the many nonsexual — and sexual — intimacies he created outside of his marriage. Unexpectedly, Anne Porter and the Jewish refugee Hamm bonded as outsiders to the Porter family, and when Fairfield went to California the following summer, Anne wrote to Ilse and asked for her help with the children. Ilse Hamm later married Fairfield's friend Paul Mattick, causing Porter to slash his own portrait of Mattick with a knife. Fairfield's plan to live with Anne and Ilse "in a triangle way" had died, and then his mother Ruth did, too.

Anne and Fairfield settled into a new life at E. 52nd Street, in a three story house. She began sleeping with another man, and Porter began pursuing the philosophy of free love. He rented an apartment in Chelsea to serve as his studio/getaway. The couple let out the upstairs rooms of their Midtown house to two black students, and the Porters began to lose some of the trappings of their previous lives, as Fairfield's interest in Communism died the true death. For a time, the house was a kind of commune.

Porter took a few lessons from the Belgian painter Georges Van Houten, but his latest inspiration was the paintings of Diego Velazquez. Of the Spanish master, Fairfield commented, "I admired what might be called understatement. Although I don't like that word, really.... He leaves things alone. He is open to it rather than wanting to twist it. I think there's more there than there is in willful manipulation.... I used to like Dostoyevsky very, very, very much. Now I prefer Tolstoy, for the same reason."

By the time Porter was 40, he and Anne were together again in spirit as well as body, for they never stopped having sex even during his affairs. A lack of recognition in the art world bothered him, but he was reassured by the attitude of his friend Willem de Kooning, who dismissed fame as the caprice of idiots and sycophants. Porter tremendously admired de Kooning and purchased many of his paintings, as well as writing the first reviews of his work that would appear in print.

At the end of the forties, the Porters moved to Southampton, buying a seven bedroom home for $25,000. The house met Fairfield's aesthetic approval and would become the scene of many famous paintings. Porter's political views and bohemian lifestyle during his youth had amounted to a rejection of his patrician background, but now he seemed to be making a move towards the bourgeois. As a nod to his former lifestyle, he rarely repaired the house or kept up the substantial grounds. As an artist, he still felt like an utter failure.

Fairfield kept an apartment on Avenue A, and began to integrate himself into the next generation of poets and artists. His attraction to the young gay poet James Schuyler verged on romance, and Fairfield began to explore his bisexuality. The younger crowd looked up to Fairfield and admired his work, and Elaine de Kooning recommended him to Art News, where he began his second life as a critic. Fairfield's politics had influenced the faux working-class realism of his first paintings, but the attraction of the art world to Abstract Expressionism was, in part, a rejection of those communist ideas. Now the painter began creating a new critical vocabulary similarly absent from political value.

Already nearing his late 40s, Fairfield was still pursuing a doctrine of free love, but in this case his target was (for a short time) the poet John Ashbery. Encouraged by his new buddies, Fairfield began writing poetry again, penning the following about Ashbery:

Young man with the narrow waist and thin

Arms, and heavy beautiful thighs of youth,

Whose green eyes under a foxy brush of

Fair hair regard me with insolent love

Porter's friendships with Ashbery and the painter Jane Freilicher would last through his life, but it was the schizophrenic Schuyler who would become a part of Fairfield's young family.

Fairfield enjoyed having the young clique at Great Spruce Head, and his children were particularly fond of Frank O'Hara. With Fairfield's six-year old daughter Katharine, Frank composed the following poem:

They say I mope too much

but really I'm loudly dancing.

I eat paper. It's good for my bone.

I play the piano pedal. I dance,

I am never quiet, I mean silent.

Some day I'll love Frank O'Hara.

I think I'll be alone for a little while.

James Schuyler became a particularly constructive/destructive figure in the life of the Porters, in some ways playing the identical role than Ilse Hamm had filled in the family. The proverbial honeymoon was lovely, but the impoverished poet eventually took advantage of Fairfield, manipulating his affections for financial and emotional gain. Despite other people's opinions of Schuyler, the Porters continue to welcome him as a guest in their many homes.

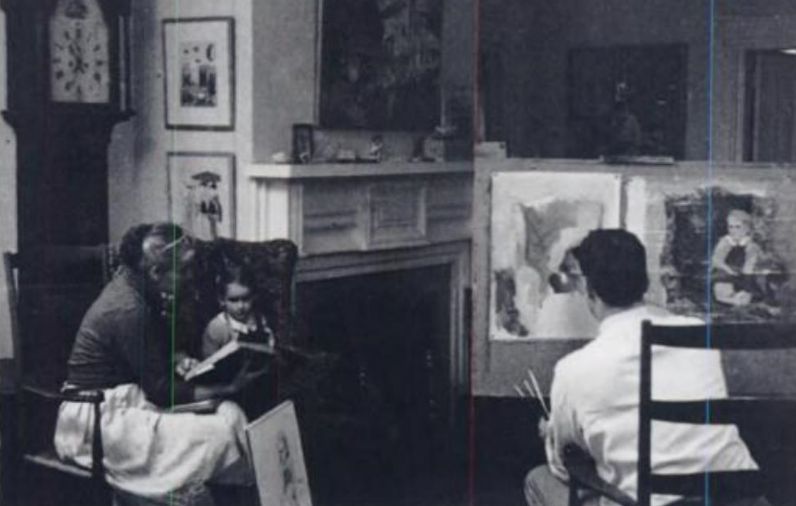

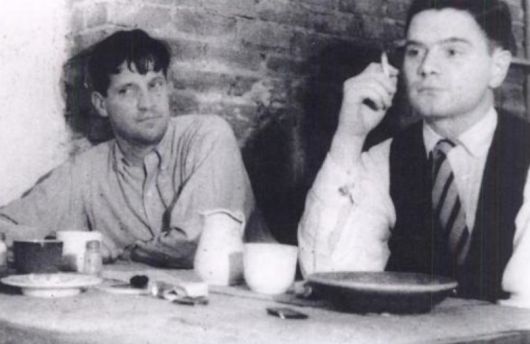

breakfasting with schuyler in 1942

When Fairfield had an important opening at Tibor de Nagy in March of 1959, O'Hara and Schuyler didn't even show up. Porter responded to this snub by approaching Frank later and telling him, "You're a shit," according to a letter Freilicher wrote to John Ashbery.

Like Frank O'Hara, the Porters were eventually turned off by the 'sleazy' Schuyler's need for control, although he returned to their good graces later in his life. This partial disillusionment with the poets who had been his friends seemed to force a change in Porter's life. He stopped reviewing for Art News in favor of writing for The Nation (they paid twice as much), and began to teach. He sold a few of his de Koonings for a small fortune.

Schuyler's first mental breakdown in 1960 brought him closer together to the Porters for a time, but it would ultimately only set him on a more destructive path. After leaving his New Haven Hospital, Fairfield picked him up. They would get on tolerably well until Schuyler reviewed Fairfield's 1962 exhibition from a psychological perspective. No doubt he could not help it, seeing demons even in places of light that the paintings held. Porter responded to Schuyler's article in a letter: "There is always psychological content. The psychological content may be what it seems, or it may be the opposite. There is psychological content to a slap in the face, or a smile at a baby, but it does not follow from this that there is art." Of Porter's close relationship with his critics, Justin Spring writes that, "Had Porter been more successful during his lifetime, the question of influence might have been raised. But he was not."

Politically, Porter's growing hatred of government, borne out of the way European cultural institutions were treated during World War II, resulted in him refusing a commission from the Art in Embassies program. He was relatively hard up for cash at this point, what with his wife, four children and Schuyler to support, but as was his custom, he never let common sense get in the way of his convictions. He even declined a university appointment in Illinois because he didn't like the architecture of Carbondale.

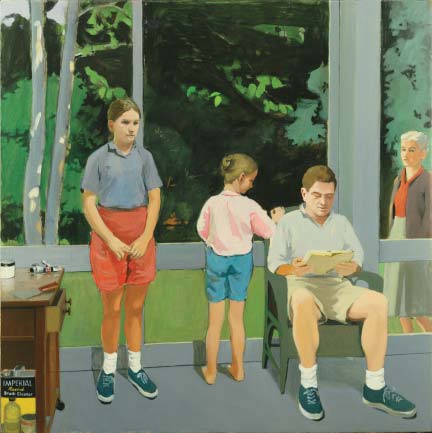

When Anne came down with hepatitis in 1963, Porter's paintings moved indoors, capturing the play of light in the interiors of his home. These were the most successful paintings of his career, both financially and artistically, feeding off the influence of the artist Alex Katz, who he admired and had reviewed. His masterpiece The Screen Porch became one of his most famous works - in the Porter family it became known as "The Four Ugly People" - and it is a frightening painting, incredibly resonant in its emotional complexity and as revealing as a church confession, with his wife outside watching her children and Schuyler in an homage to Velazquez.

Though there was some critical blowback to what some believed was Porter's bourgeois subject matter, Porter's creative process was anything but lax. He burned so many of his paintings that he had a special incinerator built for the purpose in his backyard. This was something of a blessing to history; for it is only his best works that survive, those imbued with the quiet passion of a man who could set his art in order easier than he could his own family life.

By the end of the 1960s the Porters had their fill of Schuyler and Fairfield asked him to leave the house. (The poet demurred.) His wife felt increasingly uncomfortable around the poet's depression, and made plans to replace him with a golden retriever, Bruno. Walking the dog was recommended for the aging Fairfield's health, but he tripped over Bruno's leash in 1967 and broke his arm, which temporarily limited his ability to paint. At the same time, Fairfield was reaching a mental wall. Spring attributes his lack of new work to his success - he now had money enough to live without worry, and his reputation had to a certain extent "plateaued."

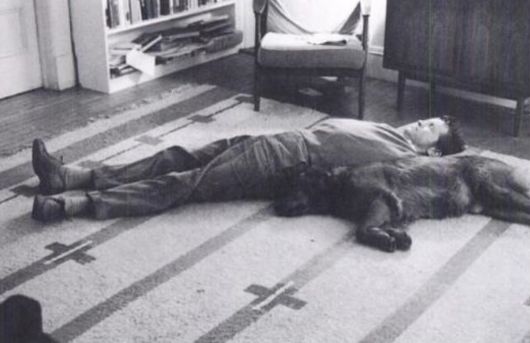

napping with Bruno

Schuyler's behavior became increasingly more erratic. While staying in Fairfield's Southampton home with the poet Ron Padgett, he threatened to kill the Padgett's young son. Friends committed him to the state mental institution, but it wasn't long before he had to be escorted back there, with John Ashbery keeping him company in the back of a patrol car. Ironically, Schuyler wrote some of his finest poetry during this period, but he also wrote savage letters to Fairfield and Anne, criticizing them in the harshest possible terms and then asking them for $5,000 for his married lover's "business."

As he transitioned into old age, Porter's interests became more eccentric. His wife had become a Catholic many years earlier, baptized on the Upper East Side, but, as a subscriber to Fate, Porter's new tastes verged more on the mystic and spiritual. He viewed the rise of technology with some concern, as most seniors do, and he became interested in the paranormal. Still his command of his interests remained fully within his intellectual control. Rather than blame himself for the troubled life of his first born, he blamed science!

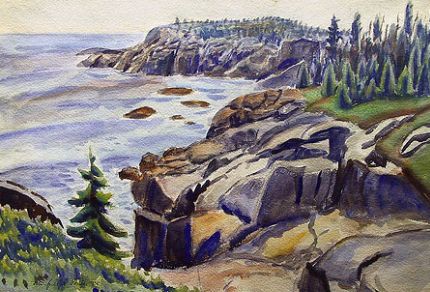

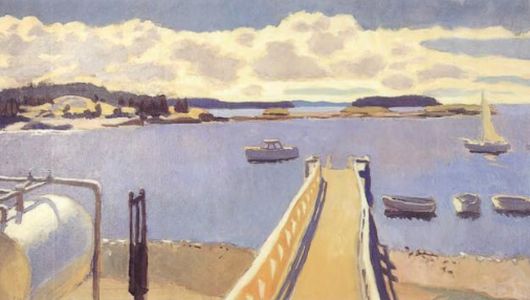

The Harbor - Great Spruce Head 1974

And yet when it came to the visual arts, he found much to admire in his contemporaries, harboring a special appreciation for the work of David Hockney. He wrote to a confined, drugged-out Schuyler that "I have painted several sunrises, with the sun in the picture, from the rocks below the house, except one from the porch. It works, more or less. I was trying to emulate the David Hockney painting I saw a few years ago, that amazed me." During a walk with Bruno in September of 1975, Porter suffered a massive coronary and died immediately. He had looked so young for his age of 68 that it came as something of a shock to his friends and family. Schuyler didn't attend the funeral, just as he had not after O'Hara's death in car accident.

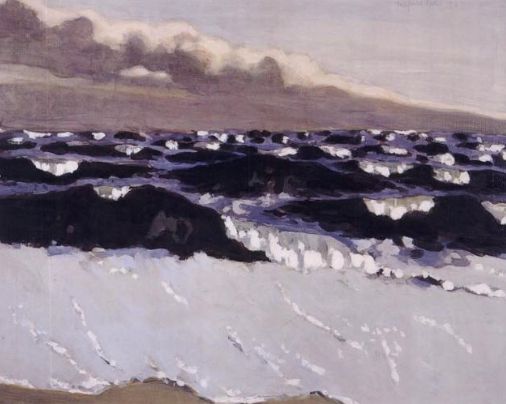

A Sudden Change of Wind, 1975

Fairfield's dual role as an artist and critic was something of a rarity. He was as talented a writer as he was an artist, and his collection of art cricitism, Art On Its Own Terms, has become a classic in its own right. His textured renderings of light approach and even exceed the grasp of his Abstract Expressionist peers. His many admirers and friends, many of whom became more famous than he could have imagined at the time of his death, have helped burnish his reputation as an artist.

Even after Schuyler had done many, many unpardonable things to him, the Porters did much for the troubled poet. This is an impressive testament to their good nature; Anne Porter even earmarked money for Schuyler's medical care after Fairfield had passed, as did Kenward Elmslie and many others. In a way, the fashion in which the group treated Schuyler was an attempt to erase guilt that generation felt at living as they did.

Fathers improve with age, and Fairfield's later children for the most part fared better than his early ones. So it was with his painting. He got better at life over time, and this is no small thing to say about a person, let alone an artist whose talent ran against the grain of the non-representational work of the time in which he lived.

Yet calling Fairfield Porter a realist is off the mark. His work does the opposite of abandoning the spiritual, it embraces the mystical, in the everyday expressions and places of his life. He had no other. So many of the finest painters of Porter's generation were immigrants from Europe who became impressive Americans. Despite not having to strive, he strove, working towards a recognition he would achieve only in death.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He tumbls here and twitters here. He last wrote in these pages about Sofia Coppola's Somewhere.

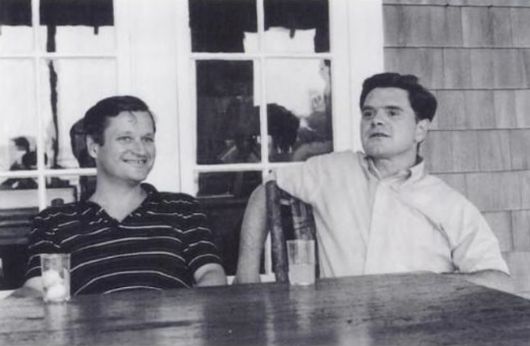

ashbery and schuyler at Great Spruce Head, 1966

"Down by the Water" - The Decemberists (mp3)

"All Arise" - The Decemberists (mp3)

"This Is Why We Fight" - The Decemberists (mp3)

Back row, from left: Lisa De Kooning, Frank Perry, Eleanor Perry, John Bernard Myers, Anne and Fairfield Porter, Angelo Torricini, Arthur Gold, Jane Wilson, Kenward Elmslie, Paul Brach, Jerry Porter, Nancy Word, Katharine Porter, unidentified woman. Second row: Joe Hazan, Clarice Rivers, Kenneth Koch, Larry Rivers, Miriam Shapiro, Robert Fizdale, Jane Freilicher, Joan Ward, John Kacere, Sylvia Maizell. Sitting and kneeling in front: Stephen Rivers, Bill Berkson, Frank O'Hara, Willem de Kooning, Alvin Novak. Photo by John Jonas Gruen.