Do They Stare Back?

Shallowness that asks to be taken seriously is an embarrassment.

Reading the reviews of Pauline Kael is rewarding because of her descriptions of actresses and actors. Beyond taking them to task for their mere talent, she was able to describe the effect they had on people through their continuing cinematic presence. Kael properly deduced that a huge part of going to the movies consisted of how the audience responded to the people on the screen, rather than simply basing her critique on the competence of the writing or the technical aspects of the cinematography. Her sentences in her radio and print reviews about the onscreen talent of the twentieth century rise to the level of expert observation of humanity in all its manifold variety. This is the second in a series, and you can find the first part here.

Ava Gardner

Gardner was one of the last of the women stars to make it on beauty alone. She never looked really happy in her movies; she wasn't quite there, but she never suggested that she was anywhere else, either. She had a dreamy, hurt quality, a generously modeled mouth, and faraway eyes. Maybe what turned people on was that her sensuality was developed but her personality wasn't. She was a rootless, beautiful stray, somehow incomplete but never ordinary, and just about impossible to dislike, since she was utterly without affectation. But to Universal she is just one more old star to beef up a picture's star power, and so she's cast as a tiresome bitch whose husband is fed up with her.

She looks blowzy and beat-out, and that could be fun if she were allowed to be blowzily good-natured, but the script here harks back to those old movies in which a husband was justified in leaving his wife only is she was a jealous schemer who made his life hell. Ava Gardner might make a man's life hell out of indolence and spiritual absenteeism, but out of shrill stupidity?

Clint Eastwood

Clint Eastwood isn't offensive; he isn't an actor, so one could hardly call him a bad actor. He'd have to do something before we could consider him bad at it. Acting might get in the way of what the movie is about — what a big man and a big gun can do. Eastwood's wooden impassivity makes it possible for the brutality in his pictures to be ordinary, a matter of routine. he may try to save a buddy from getting killed, but when the buddy gets hit no time is wasted on grief; Eastwood couldn't express grief any more than he could express tenderness. With a Clint Eastwood, the action film can — indeed, must — drop the pretense that human life has any value. At the same time, Eastwood's lack of reaction makes the whole show of killing seem so unreal that the viewer takes it on a different level from a movie in which the hero responds to suffering.

Woody Allen

Allen appears before us as the battered adolescent, scarred forever, a little too nice and much too threatened to allow himself to be aggressive. He has the city-wise effrontery of a shrimp who began by using language to protect himself and then discovered that language has a life of its own. the running way between the tame and surreal — between Woody Allen the frightened nice guy trying to keep the peace and Woody Allen the wiseacre whose subversive fantasies keep jumping out of his mouth — has been the source of the comedy in his films. Messy, tasteless, and crazily uneven (as the best talking comedies have often been) the last two pictures he directed — Bananas and Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex — had wild highs that suggested an erratic comic genius. The tension between his insecurity and his wit make us empathize with him; we, too, are scared to show how smart we feel.

And he has found a nonaggressive way of dealing with urban pressures. He stays nice; he's not insulting, like most New York comedians, and he delivers his zingers without turning into a cynic. We enjoy his show of defenselessness, and even the I don't-mean-any-harm ploy, because we see the essential sanity in him. We respect that sanity — it's the base from which he takes flight. At his top, in parts of Bananas and Sex, the inexplicably funny took over; it might be grotesque, it almost always had the flippant, corny bawdiness of a frustrated sophomore running amok, but it seemed to burst out — as the most inspired comedy does — as if we had all been repressing it. We laughed as if he had let out what we couldn't hold in any longer.

Isabelle Adjani

Only nineteen when the film was shot, Isabelle Adjani is much younger than the woman's she's playing. She hardly seems to be doing anything, yet you can't take your eyes off her. You can perceive why Truffaut has said that he wouldn't have amde this "musical composition for one instrument" without Isabelle Adjani. She has a quality similar to Jean-Pierre Leaud's in The 400 Blows — not a physical resemblance but a similar psychological quality. The awareness and intelligence are there, but nothing else is definite yet; the inner life has not yet taken outer form, and so in the movie you see the downy opacity of a face in process, a character taking shape. We keep staring at Adele to see what the face means.

Isabelle Adjani has been a professional actress since she was fourteen without tightening; one French directors says that she's James Dean come back as a girl. Considering how young she is, her performance here is scarily smart. She knows how to alert us to what Adele conceals; she's unnaturally quiet and passive, her blue eyes shining too bright in a pale flower face. Truffaut had the instinct not to age her with makeup in the course of the film; we can see that years are passing, but the tokens of time are no more than reddened eyes, a pair of glasses, tangled hair, a torn, bedraggled gown.

Robert De Niro

De Niro amply convinces one that he has it in him to become the old man that Brando was. It's not that he looks exactly like Brando but that he has Brando's wary soul, and so we can easily imagine the body changing with the years. It is much like seeing a photograph of one's own dead father when he was a strapping young man; the burning spirit we see in his face spooks us, because of our knowledge of what he was at the end.

In De Niro's case, the young man's face is fired by a secret pride. His gesture as he refuses the gift of a box of groceries is beautifully expressive and has the added wonder of suggesting Brando, and not from the outside but from the inside. Even the soft, cracked Brando-like voice seems to come from the inside. When De Niro closes his eyes to blot out something insupportable, the reflex is like a presentiment of the old man's reflexes. There is such a continuity of soul between the child on the ship, De Niro's slight, ironic smile as a cowardly landlord tries to appease him, and Brando, the old man who died happy in the sun, that although Vito is a subsidiary character in terms of actual time on the screen, this second film, like the first, is imbued with his presence.

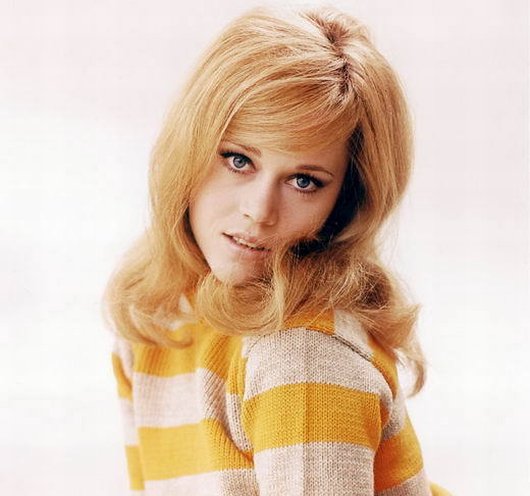

Jane Fonda

Jane Fonda having sex on the wilted feathers and rough, scroungy furs of Barbarella is more charming and fresh and bouncy than ever — the American girl triumphing by her innocence over a lewd comic-strip world of the future. She's the only comedienne I can think of who is sexiest when she is funniest. (Shirley MacLaine is a sweet and sexy funny girl, but she has never quite combined her gifts as Jane Fonda does.) Jane Fonda is accomplished at a distinctive kind of double take: she registers comic disbelief that such naughty things can be happening to her, and then her disbelief changes into an even more comic delight.

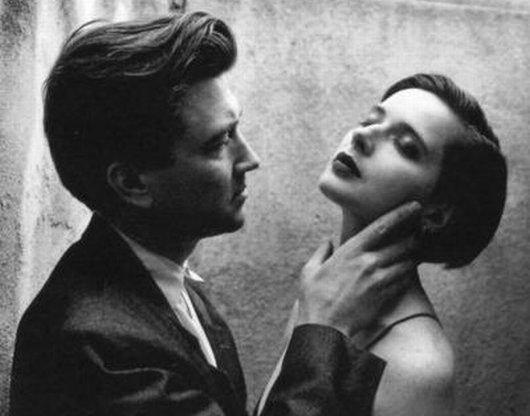

Dirk Bogarde

As the philosophy-don husband, Dirk Bogarde is just about perfect: he acts like a man who's had a spinal tap. He's a virtuoso at this civilized, stifled anguish racket, better even than Ralph Richardson used to be at suppressed emotion because he's so much more ambiguous that we can't even be sure what he's suppressing. He aches all the time all over, like an all-purpose sufferer for a television commercial — locked in, with a claustrophobia of his own body and sensibility.

Bogarde looks rather marvelous going through his middle-aged frustration routines, gripping his jaw to stop a stutter or folding in his arms to keep his hands out of trouble. The Ralph Richardson civilized sufferer was trying to spare others pain, but Bogarde isn't noble: he goes through the decent motions because of training and because of an image of himself, but he's exquisitely guilty in thought — a mouse with the soul of a rat. He compulsively tells little half lies that he attempts to make true and hesitates before each bit of truth he calculatingly parts with.

Isabella Rossellini

Rossellini doesn't show anything like the acting technique that her mother, Ingrid Bergman, had, but she's willing to try things, and she doesn't hold back. Dorothy is a dream of a freak. Walking around her depressing apartment in her black bra and panties, with blue eyeshadow and red high heels, she's a woman in distress right out of the pulps; she has plushy, tempestuous look of heroines who are described as "bewitching." (She has the kind of nostrils that cover artists can represent accurately with two dots.)

Rossellini's accent is useful: it's part of Dorothy's strangeness. And Rossellini's echoes of her mother's low voice help to place this kitschy seductress in an unreal world. She has a special physical quality, too. There's nothing of the modern American woman about her. When she's naked, she's not protected, like the stars who are pummelled into shape and lighted to show their muscular perfection. She's defenselessly, tactilely naked, like the nudes the Expressionists painted.

Once, in Berkeley, after a lecture by LeRoi Jones, as the audience got up to leave, I asked an elderly white couple next to me how they could applaud when Jones said that all whites should be killed. And the little gray-haired woman replied, "But that was just a metaphor. He's a wonderful speaker."

"Parade" - Justice (mp3)

"Civilization" - Justice (mp3)

"Helix" - Justice (mp3)

The second studio album from Justice, entitled Audio, Video, Disco, will be released on October 24th.