I Paint

by MOLLY LAMBERT

Because I didn't go to art school, a class in the painting department was out of the question. Instead I signed up for the introductory painting class in the illustration department. The illustration department was a sort of more old style branch of the school, like what I imagined a 1950s art school to be like. The idea that you could teach somebody how to make art seemed as ridiculous to me as the idea you could teach someone how to write. You either could or you couldn't. You can or you can't.

I was deciding between drawing and painting. Like most people, I maintain a variety of side talents that I can imagine could be my main talent if only I were a little more focused on it, and I am very talented at drawing. I spent the majority of my school years drawing in notebooks during class and while my style is more caricaturish than strictly realistic, I am pretty fucking good. So the prospect of drawing in a real art class was exciting, as was that of life models, which seemed really official and traditional. But given the choice, the asceticism of drawing; the discipline and repetition verging on tedium, the limited supplies? It didn't stand a chance against the painting class.

Painting, with all its accessories and trappings, had mystique I could not explain. It appealed deeply to my Irish-Catholic half, the side of me that enjoys going to botánicas and cataloguing sins and saints. But it mostly had to do with paintings. With the way that observing certain paintings could induce really powerful feelings in me.

I wanted to see what I had inside. The same way I was sure I could write a great song if I only knew how to play the guitar, I was convinced I had paintings in me. I was sure they would come out of me as soon as I got a brush in my hand. That when I had a little technique and a canvas in front of me it would be impossible to contain them.

On the first day of class I ran into a really pretty girl I kind of knew who had inspired me a few months before to stop wearing bras entirely after seeing her at a restaurant in a wife-beater without one. "Wow, cool" I'd thought admiringly, "She doesn't give a fuck. And neither do I!" I tend to overdo it when I go to an extreme. She was on her way to the drawing class, and encouraged me to come so we could be in it together. I thought about it for a second. I loved making friends, especially very attractive ones. But I was really committed to the idea of the introductory painting class. To painting.

Every week after that I'd see her in the stairwell. We'd greet each other, then she'd turn the other way to head into the drawing class. Even when I didn't see her I would imagine her going to the drawing class to sketch and long to have followed her that first day. Being good at drawing, it turned out, had no bearing on other kinds of art.

The painting teacher was a tall willowy bald man in a tunic with the kind of round frame glasses favored by older artist types. He commuted in weekly from New York. He was cold, with a zen master manner that appealed to me. I decided immediately that I liked him. In retrospect he was gay but I never thought about it at the time. During the first class he showed us some of his recent work; a series of grayscale oil paintings of the interior of a washing machine. "This guy is fucking serious," I thought admiringly.

I was a senior in college, avoiding thinking about what I was going to do exactly after graduating. My boyfriend of a year had gone abroad and I was unprepared to feel so weird about our breakup. I'd decided not to do a thesis because a big project that was due all at once and mostly unsupervised seemed like the worst possible idea for a Ferris Bueller finish everything at the last minute person like me. But my friends were incredibly busy, and I had too much time to think about how I really felt (terrible).

Painting seemed like an elegant solution to all my problems. In lieu of a thesis, it would give me one thing to focus on. Going down to the art school would provide variety in my routine and I could devote all my unspoken for spare time to working on my paintings. To becoming a painter, a thing I was sure I could also be. It didn't occur to me that I might later resent my own arrogant blitheness that it would be easy.

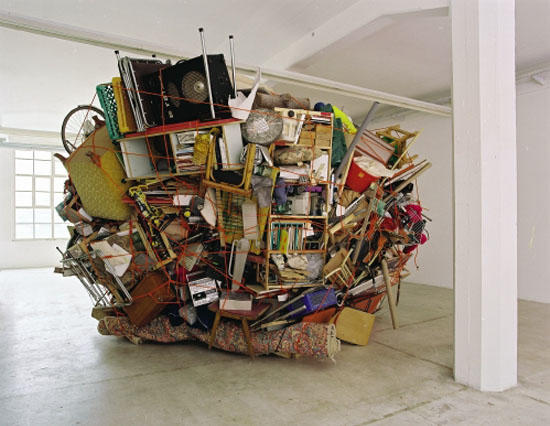

I bought as many art supplies as I could afford, which was not all that many because I learned quickly that oil painting is a truly expensive pursuit. I was attracted to the accessories, the tinctures and tools. But I'd had no idea just how many accessories there really were, how much alchemy and liniment went into preparing the canvases. How familiar I'd soon become with the nightmarish poetic phrase "rabbit-skin glue."

I might have known some of this if I had asked any of my many, many friends who painted and took art classes even the most rudimentary questions about what a painting class might entail in advance of signing up for the painting class at the art school. But I had just charged in confidently like an idiot, like I generally always did.

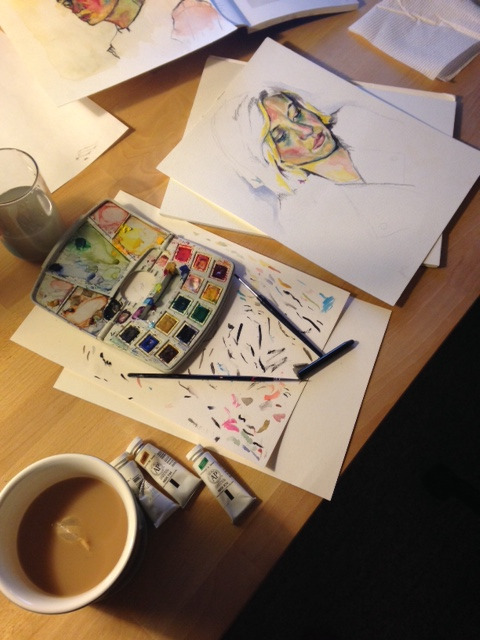

The first few weeks of the class knocked the arrogance right out of me. I couldn't do anything. I had no knowledge, no background, no color theory. I thinned the paint wrong. I held the brush wrong. I couldn't mix colors correctly to save my life. Everyone else in the class seemed to know exactly what they were doing. They could all paint.

I asked for help every minute, but it didn't help any. I was terrible. Relentlessly terrible. Terrible in new and inventively terrible ways, ways that seemed to baffle the teacher and any classmates who caught a glance of my canvases. There was a wall between me and being any good at painting, and I could not get over the wall. I could barely even make out its sides. But I felt it there in front of my face, blocking me from my goal.

All we painted were still lifes. There would be three set-ups and over three hours, and each session was a lesson for me in abject failure. I was the worst person in the class by a long shot and it was humiliating. I fucking sucked. The teacher would come stand near me and just sort of shake his head. He was right to be confused. Why was I there?

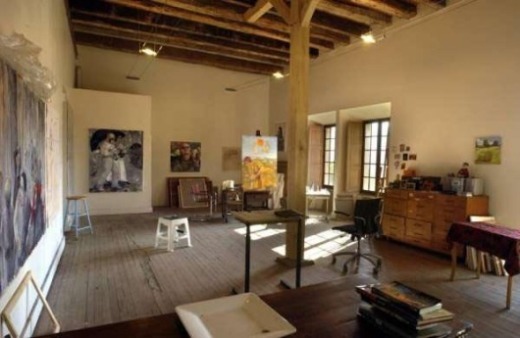

Our homework was the same as the classwork. Three still lifes, a different color scheme each week. I went to the art building on my campus and set up my easel and materials by the picture window. I was jealous of the studio cubicles, especially of the clippings taped up inside, your own space to just dwell on inspirations and ideas.

Having a cubicle means you are a real artist, I thought. I saw the real artists I knew, working on their thesis projects, utterly consumed in themselves. "Why didn't I do a thesis? Why didn't I write a novel? Or short stories? Because I am a fucking idiot."

Then I tried to paint the shells that I was looking at again, and failed. Each attempt a failure in a totally different way. In one the shells are much too pink. In another the arrangement appears two dimensional. I found a new way to fail every time. I painted slower, then faster. Sober, then high. I went to the studio drunk and ended up falling asleep on the bench in the lobby. I woke up and outside the glass it was snowing.

I began to dread painting, because I dreaded being terrible. I hated the endless inevitable failures that were my attempts at translating an image from real life onto a canvas. I did not enjoy being terrible at it, and the classwork and homework were so rigid that there was no possibility of adjusting the subject matter to my outsider style, as I had done in other fields such as dance. I wondered a lot why it was that I so vehemently couldn't enjoy something I wasn't good at. How egotistical that was.

I was accustomed to picking things up easily, impressing and occasionally frustrating others with the seeming effortlessness with which I could pick new things up at will. There was no picking up painting. It was hard work and I was out of my depth. And I could tell. And the teacher could really tell, and he was getting sick of my excuses.

I had been able to bullshit my way through a lot of things in life, but I could not bullshit a painting. Furthermore, there was no failing, because I had already failed a class earlier in the year. I needed the credit to graduate. I stopped going to class.

My refusal to attend coincided with a big snowstorm after a long weekend and I wrote off the first couple weeks of missed classes as weather related. The third week I was just slacking and knew it. The teacher knew it too. He e-mailed to say he'd fail me if I didn't show up the next week. "This guy is fucking serious," I thought irritatedly.

I came back to class and tried to be less of an asshole, but was almost definitely even more of one in this attempt. The only place I really thrived in the class was during the critiques. Oh I had opinions about everyone's paintings. Positive ones! I could talk all day about what I liked about one painting or another. I loved talking about what I liked about things. I was still the worst painter but I sure talked the most during the crits.

I thought a lot about this tendency I had, towards language. How when I saw a tree I immediately began describing it in my head. I had talked about it with my boyfriend right before he'd left. He had countered that he never did that. That when he looked at the tree he saw only the tree. And if he started to break it down, it was into colors and shapes. Images, not words. I didn't understand. He never read for pleasure either.

Painting seemed more mystical than ever. Now that my fantasy of being good at it had been destroyed and replaced with the truth (that I sucked) I was in complete awe of anyone with any painting talent. Anyone who was better than me was a genius. I admired those with talents I couldn't master. It was like being good at a sport.

I continued to go to class. I stopped dreading failure. I didn't expect failure, but neither was I devastated when it happened. My ego was no longer in it. I had no natural talent for painting, but that didn't mean none could be cultivated. Sometimes I'd feel as though I had gotten one detail about the set-up across in my painting, and that would satisfy me enough to keep going. I had a couple of stupid winter hats, and whenever I wore one I was mistaken for an art student (and then asked directions).

It was not sudden but I began to understand. I started to look at things differently. I learned to think about the quality of the light. How things appeared to be different colors depending what time of day it was. How to observe buildings. How to describe without words. How this was a whole other language, a universal one, and I did know it. I had just been trying too hard to force everything into my own native dialect.

We stopped doing still lifes and started painting nudes. I liked the life models. I felt connected to my own brushstrokes and color choices in a way I previously hadn't. Whatever it was I was trying to comprehend, I couldn't possibly put it into words, and I understood now how that was the point (zen master indeed). I had climbed the wall.

As with any fallow time, when I think about this period of my life I just wind up romanticizing it. I remember how cold I was and how heartbroken, how thwarted I felt and how hurt. I see myself riding my bike to the studio through the snow, listening to Southern gangsta rap on headphones, the music you listen to that helps blunt your feelings (rather than the miserable music you use to indulge them) with my portfolio slung over my shoulder. How determined I must have looked. It makes me laugh.

I proposed a series of paintings of small toys for my final project and was approved. I hung out with my other recently single friend who was an actual painter and we worked on our art in her attic room which had a big awesome skylight. We smoked joints and listened to Electric Light Orchestra albums on her record player while we painted. That I thought I was miserable that semester seems so ridiculous now.

I had no idea if I was going to pass the painting class given those three absences, and passing was necessary for my graduating, and graduating seemed crucial given how much money I was now (am) in debt for. I was nervous regarding a lot of other things about my immediate future, absolutely none of which would turn out to matter at all.

When I think of the thing I might have written that semester had I dedicated myself to it I feel no remorse. No regret that I failed to take on a big writing project instead. No curiosity about what I might have produced. It would never have been any good. You cannot produce something great on purpose or on schedule. The painting class was more important, akin to psychedelics. It was the most important class I ever took.

The teacher surveyed my final project; small still lifes of toy cars. In his affectless tone he said something measuredly complimentary about my curve towards improvement and I felt myself stir with deep pride. How could I tell him how much it meant that he had tolerated me, had humbled me, had let me learn the lesson for myself? And then how much I had learned? I couldn't tell him, so I didn't. I passed painting with a C.

Molly Lambert is the managing editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Los Angeles. She twitters here and tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about her feud with Jack Nicholson.