Turn Back Time

by KARINA WOLF

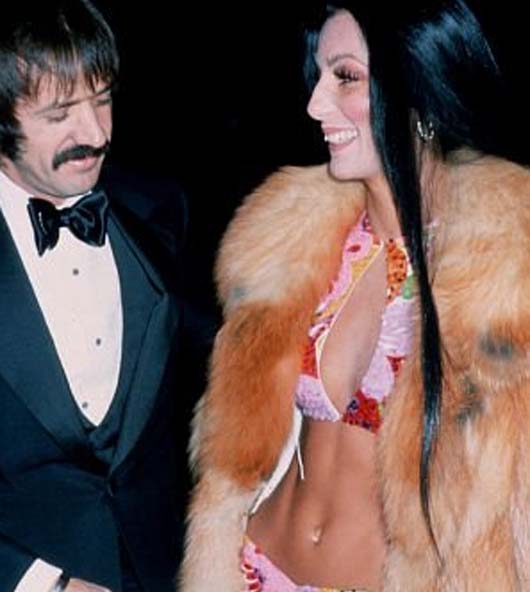

1987 was a good year for Cher: Suspect, The Witches of Eastwick, a popular fragrance, a pop-metal album, a bagel artisan boyfriend, and a best actress Oscar for Moonstruck. As Pauline Kael wrote, in Moonstruck, Cher was funny and sinuous and devastatingly beautiful.

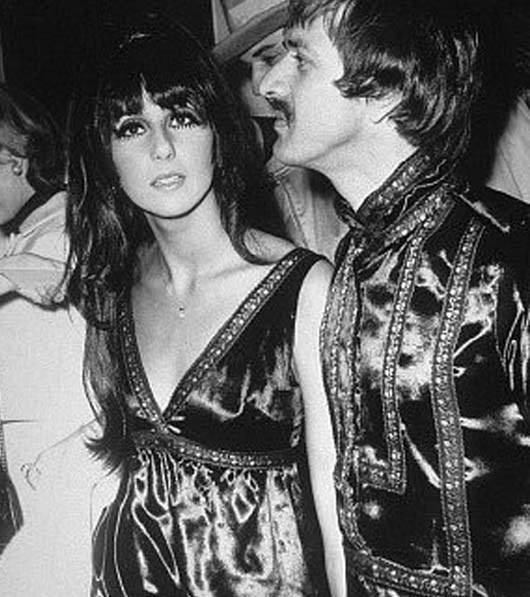

Yes, beautiful. Like Fitzcarraldo's steamship lurching over a Peruvian mountain, Cher had arrived at a vertiginous instant of surgical perfection: nose, slimmed, teeth straightened and capped, mushroom cloud of hair, presumably not her own, but at least a believably natural hue. A few years later, she was sporting synthetic weaves and blue eyes, and promoting "The Shoop Shoop Song." That's not the Cher any of us want. Give us "Gypsies, Tramps, and Thieves"; give us "Half Breed."

I was smitten, maybe because she was a cross between my other two other childhood idols: Lynda Carter, who made being a brunette bearable (brown in the 70s and 80s was like ginger today) and Dolly Parton, who instilled honor in being a painted woman.

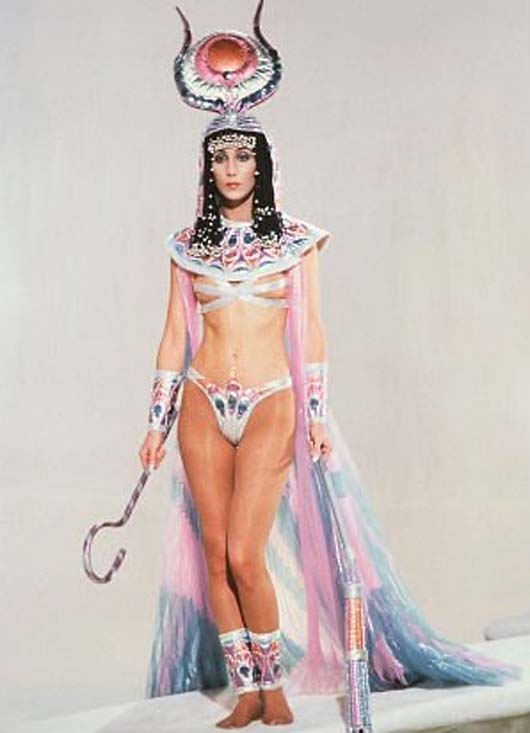

Some well-meaning relative bought me a bottle of Cher's perfume, Uninhibited. I listened to Cher's metal version of Nancy Sinatra's "Bang Bang" and to what I think is the best-ever unisex karaoke anthem, "If I Could Turn Back Time."

But really what appealed was the movie; not just the transformation of Loretta, Cher's dowdy widow, into permed, borough prom queen, but the pleasure of spending time in a Bococa brownstone with the family. (This is post-Godfather but pre-Sopranos).

I don't know, said my mother, if these characters are setting a good example. I think she disapproved of the scene in which, after a bloody steak and a glass of whiskey, Nicolas Cage throws over his kitchen table, hoists Cher in his arms and takes her to bed.

Obviously, Moonstruck is not a field guide to building intimacy. But it is the I-ching for Jungian romantics:

Why do men chase women?

God took a rib from Adam and made Eve. Maybe men chase women to get the rib back.

Why would a man need more than one woman?

Because he fears death.

On whether to accept an ill-chosen engagment ring:

Everything is temporary. That don't excuse nothing.

The correct response to an ill-timed "I love you"?

Snap out of it.

There's also the definition of a good suit (comes with two pairs of pants); a good restaurant customer (a bachelor); the right meal to eat before a flight to Sicily (manicotti); the proper way to propose to a woman; and the exact time to hold a wedding (after mom's dead).

It's a corroboration of Norman Jewison's and the actors' skills that this dialogue is remotely plausible; they achieve exactly the right tone for the overheated characters. Imagine Al Pacino, who was originally pursued for the Nic Cage role, chewing through these lines:

I lost my hand. I lost my bride. Johnny has his hand, Johnny has his bride. You want me to take my heartbreak, put it away and forget it? Is it only a matter of time before a man gives up his one dream of happiness?

John Patrick Shanley's original title was The Bride and The Wolf, suggesting a scrapped Tarantino-Romero collaboration. Really it's a domestic drama with mythical dimensions.

Loretta wants to be a bride — will the groom be the safe choice (a lamb) or the dangerous one (a wolf)?

Nic Cage, festering like a bread-baking Hephaestus, is crazy like a wolf. Or so Loretta tells him when he relates why he lost his hand and his fiancée from a bread-slicing accident. You're a wolf. That woman didn't leave you. She was a trap for you. And you — you chewed off your own foot to get away.

Moonstruck is the last modern record of an adult receiving or perpetrating a hickey. It's also the last time a prosthetic could be seen as a plausible impediment to marriage (if only Heather Mills had been around as an example for Ronny).

It was released when Pauline Kael was still writing for The New Yorker, which means that there were still movies being made worthy of Kael plaudits. See Wes Anderson for further details.

Moonstruck has the visual dullness of mid-80s urban films, a bit of claret mixed in the granite and beige and inky palette. But Kael recognized its conceit: "it's an honest contrivance – the mockery is a giddy homage to our desire for grand passion. With its special lushness, it's a rose-tinted black comedy." Maybe that's the danger my mother warned about; the movies suggests that under a particular planetary configuration, we will be *pleasurably* confronted by our repressed passions.

Karina Wolf is the senior contributor to This Recording. She last wrote in these pages about Tennessee Williams and his sister. She tumbls here.

"If I Could Turn Back Time" - Cher (mp3)

"Believe" - Cher (mp3)

"Walking in Memphis" - Cher (mp3)