Lethal Arrangements

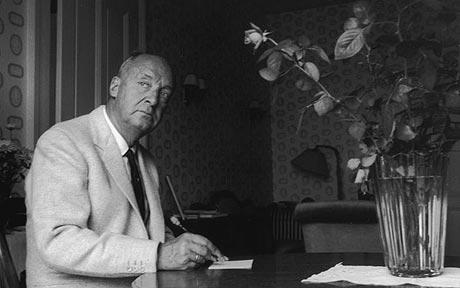

When he answered Vladimir Nabokov's first letter on November 12th of 1940, Edmund Wilson resembled many American intellectuals during the early days of the Cold War: his sympathies lay with the Soviet Union. Since he had never experienced the oppression of the Soviet regime firsthand, Wilson's ideas were necessarily absurd and fantastic. You would think that meeting someone who fled from those restrictions would at least slightly alter his worldview. The fact that this person was Vladimir Nabokov would seem to increase the likeliness of his conversion. Yet some men are more easily captivated by ideas than people, and the ones that drew Edmund Wilson were akin to a virulent disease.

Their relationship, as encapsulated by the letters included here, was direct, honest, and sometimes incendiary. Nabokov was better at taking criticism from people who didn't deserve to empty his bedpan than any writer of his talent. Most geniuses live in the thrall of their dominance - Nabokov had to suspect he was the greatest artist of his generation, but he never behaved that way. He may have felt Wilson misguided, but he tried his best to accommodate an ignorant American socialist who was kind to him and his family and a shitheel to everyone else.

December 24, 1945

Dear Bunny,

There are several reasons why Hamlet, even in the hideous garbled versions current on the stage, should be attractive both to the caviar eater and the groundling:

(1) everybody likes to see a ghost on the stage;

(2) kings and queens are also attractive;

(3) the number and variety of lethal arrangements are unsurpassed and thus most pleasing-

(a) murder by mistake,

(b) poison (in dumb show),

(c) suicide,

(d) bathing and tree climbing casualty,

(e) duel,

(f) again poison-

and other attractions backstage. Incidentally it has never occurred to critics to note that Hamlet does kill the king in the middle of the play; that it turns out to be Polonius does not alter the fact of Hamlet having gone and done it. Anthology of murder.

We somehow hoped that you would come here these days. I am working furiously at my novel (and very anxious to show you a couple of new chapters). I detest Plato, I loathe Lacedaemon and all Perfect States. I weigh 195 pounds.

cordially yours,

V. Nabokov

Wilson had sent some drawings of butterflies to Nabokov, and this letter followed.

March 24, 1946

Dear Bunny,

Many thanks for the lepidoptera: most of them belong to Ebriosus ebruis but there is a good sprinkling of the form vinolentus. At least one seems to be an authentic A. luna seen through a glass (of gin) darkly; the person who drew these insects possessed the following attributes:

1) was not an entomologist;

2) was vaguely aware of the fact that a lepidopteron has four, and not two, wings;

3) in the same vague groping way was more familiar (very comparatively, of course) with moths (Heterocera) than butterflies (Rhopalocera);

4) the latter suggests that at one time he may have spent the month of June (for the luna lurking at the back of his mind occurs only in early summer) in a country-house in New York state; warm dark fluffy nights.

5) He was not a smoker since the empty Regent cigarette box with the sketches would have contained a few crumbs of tobacco if he had been using its contents just before; it had been lying about and he just picked it up. (in margin:) The reasoning here is uh-uh.

6) May have been together with a lady: she lent him the scissors to cut out of the cigarette wrapping paper the specimen of Vino gravis; the scissors were small pointed scissors (because an attempt was made, but not pursued, to cut out one of the months on the paper napkin).

7) There is a faint smudge of lipstick on the lid of the box.

8) He had not been eating when he started to sketch - because the first one (the pseudo luna) was drawn on the paper napkin when it was still folded.

9) He was not a painter but may have been a writer; this is however not suggested by the presence of a fountain pen; quite possibly he borrowed the pen from the lady.

10) The whole thing may have started from a curlicue; but the further development was conscious.

11) There is a cherteniata or diablotins strain in the general aspects of the moths.

12) Was under the impression that a moth's body is all belly: he segmented it from tip to top; this may mean that he believed in the stomach rather more than in the heart: e.g., he would be apt to explain this or that action on material, and not sentimental, grounds.

13) The lady was doing the talking.

Well, Watson, that's about all. I am eagerly looking forward to seeing you! Your book is causing quite a "sensation" among my literary friends here. Neither am I attracted by Marion Bloom's "smellow melons" or Albertine's "bonnes grosses joues", but I gladly follow Rodolphe ("Avancons! Du courage!") as he leads Emma to her golden doom in the bracken. I mean, it was in that purely physiological sense that I criticized your hero's prouesses.

Lovingly yours,

V.

Nabokov had sent along a draft of his dystopian novel to Wilson.

January 30, 1947

Dear Vladimir:

I was rather disappointed in Bend Sinister, about which I had some doubts when I was reading the parts you showed me, and I will give you my opinion, for what it is worth. Other people may very well think otherwise: I know, for example, that Allen Tate is tremendously excited about it - he told me that he considered it "a great book." But I feel that, though it is crammed with good things - brilliant writing and amusing satire - it is not one of your greatest successes. First of all, it seems to me that it suffers from the same weakness as the play about the dictator.

You aren't good at this kind of subject, which involves questions of politics and social change, because you are totally uninterested in these matters and have never taken the trouble to understand them. For you, a dictator like Toad is simply a vulgar and odious person who bullies serious and superior people like Krug. You have no idea why or how the Toad was able to put himself over, or what his revolution implies. And this makes your picture of such happenings rather unsatisfactory. Now don't tell me that the real artist has nothing to do with the issues of politics. An artist may not take politics seriously, but, if he deals with such matters at all, he ought to know what it is all about. Nobody could be more contemplative or cooler or more intent on pure art than Walter Pater, whose Gaston de Latour I have just been reading; but I declare that he has a great deal more insight into the struggle between Catholicism and Protestantism that was raging in the sixteenth century than you have into the conflicts of the twentieth.

You aren't good at this kind of subject, which involves questions of politics and social change, because you are totally uninterested in these matters and have never taken the trouble to understand them. For you, a dictator like Toad is simply a vulgar and odious person who bullies serious and superior people like Krug. You have no idea why or how the Toad was able to put himself over, or what his revolution implies. And this makes your picture of such happenings rather unsatisfactory. Now don't tell me that the real artist has nothing to do with the issues of politics. An artist may not take politics seriously, but, if he deals with such matters at all, he ought to know what it is all about. Nobody could be more contemplative or cooler or more intent on pure art than Walter Pater, whose Gaston de Latour I have just been reading; but I declare that he has a great deal more insight into the struggle between Catholicism and Protestantism that was raging in the sixteenth century than you have into the conflicts of the twentieth.

I think, too, that your invented country has not served you particularly well. Your strength lies so much in precise observation that, in combining German and Slavic, you have produced something that does not seem real - especially as one has always to compare it with the hideous contemporary reality. Beside the actual Nazi Germany and the actual Stalinist Russia, the adventures of your unfortunate professor have the air of an unpleasant burlesque. I never believed in him much from the beginning, was never moved by the wife and son; but I thought you were going eventually to turn him inside out, take the whole thing apart and show that our ideas of injustice and tragedy were purely subjective or something of the sort. (I'm sorry that you gave up the idea of having your hero confront his maker.) As it is, what you are left with on your hands is a satire on events so terrible they really can't be satirized - because in order to satirize anything you have to make it worse than it is.

Another thing, Bend Sinister is (with the exception of that play) the only thing of yours that has seemed to me to have longueurs. It doesn't move with the Puskinian rapidity that I have always admired in your writing. I know that you have been aiming here at a denser texture of prose than in a thing like Sebastian Knight, and some of the writing is very remarkable, but there are moments,-don't send me an infernal machine! - when I am reminded of Thomas Mann.

You have certainly improved it a lot, though, since the manuscript I saw. I expect to reread it when I get the book and find much that I didn't appreciate. By the way I see that I was wrong in changing the gender of derriere in the proof - for some reason, I always think of it as feminine. One thing I believe I forgot to correct is the girl's saying that the man has "a regular sense of humor." This is impossible. She would have to say either that he had a wonderful sense of humor or that he was a regular card (I don't believe you want regular here at all).

About the New Yorker: I'll take up it with them. Wallace Shawn, not Mrs. White, is the person to talk to about it. The thing to do is for you to write him a letter, and I'll speak to him about it when I call him up again. I think it is a good idea. Hamilton Basso and I now do one review apiece a month, but I still owe them several from my last year's contract, so for awhile things won't look much different,.

Is it Nicholas who is doing the broadcasting? I didn't know he was back from Europe.

Before giving up Henry James, try the long novel called The Princess Casamassima and the first volume of his autobiography, A Small Boy and Others. These represent two departments of his work which you may not yet have sampled.

We are living up here in Wellfleet. The days become rather monotonous, but we are quietly working for civilization. Nina is staying in the house with us till Paul gets back from China. We don't expect to get to New York till sometime late in March. I'm still working on my book about my trip to Europe. By the time it comes out next fall, it will be deliriously out of date.

Yes: I'm completely finished with Laughlin - wrote him long ago, when he asked me to do some favor, telling him what I thought of his practices. I regard it as a calamity that he is bringing out a book of your stories. Do try to have Holt take it over.

I wish that, when you write me, you wouldn't transliterate your Russian, as it is more trouble for me that way. I always have to put it back before I can make out what it is.

Love to Vera. I hope she will forgive me for not liking Professor Krug as well as some of your other creations.

As ever,

EW

Nabokov responds to some of Wilson's corrections on the novel's manuscript, and fires back.

February 9, 1947

Dear Bunny,

Spasibo za pismo i zamechania - sorry, I thought I was giving you little informal lessons of Russian by inserting those Russian words - but apparently my method was wrong.

The point of L'egorgerai-je ou non (To be or not to be) is, of course, the well-known hypothesis that what Hamlet meant by the first words of his soliliquoy was: "Is my killing of the king to be or not to be?"

"Cries on havoc" is correct - it is so in Shakespeare.

"Ghostly apes," etc., is of course not supposed to sound like Shakespeare. The meter is not of his time.

"Lower and belowed" is meant to illustrate a common German mistake ("w" for "v") when printing propaganda in English.

"Recurved" is extensively used in zoological works ("Krug in the larval stage...") Look up, for instance, "ibex" in Webster.

"Froonerism" is a combination of a Freudian lapsus lingui and a spoonerism.

I too had my doubts as to whether you would appreciate the atmosphere of my book, - especially when you praised Malraux. In historical and political matters you are partisan of a certain interpretation which you regard as absolute. This means that we will have many a pleasant tussle and that neither will ever yield a thumb (inch) of terrain (ground).

I am writing another book which, I hope, you will like better.

Vera joins me in sending you our love.

Yours

V.

edmund

edmund

In this letter, Nabokov finally responds to Wilson's contentions about his political background.

February 23, 1948

Dear Bunny,

You naively compare my (and the "old Liberals'") attitude towards the Soviet regime (sensu lato) to that of a "ruined and humiliated" American southerner towards the "wicked" North. You must know me and "Russian Liberals" very little if you fail to realize the amusement and contempt with which I regard Russian emigres whose "hatred" of the Bolsheviks is based on a sense of financial loss or class degringolade. It is preposterous (though quite in line with Soviet writings on the subject) to postulate any material interest at the bottom of a Russian Liberal's (or Democrat's or Socialist's) rejection of the Soviet regime.

I really must draw your attention to the fact that my position in regard to Lenin's or Stalin's regime is shared not only by Constitutional Democrats, but also by the Social Revolutionaries and various socialist groupings, and that Russian culture was built by liberal thinkers and writers which I think rather spoils your neat simile of "North and South." To spoil it completely I may add that the rather local and special difference between the North and South is much more comparable to that between first cousins, between say, Hitlerism (Southern race prejudice) and the Soviet regime, than it is to the gap existing between fundamentally different systems of thought (totalitarianism and liberalism).

Incidental but very important: the term "intelligentsia" as used in America (for instance, by Rahv in The Partisan is not used in the same sense as it was used in Russia. Intelligentsia is curiously restricted here to avant-garde writers and artists. In old Russia it also included doctors, lawyers, scientists, etc., as well as people belonging to any class or profession. In fact a typical Russian intelligent would look askance at an avant-garde poet. The main features of the Russian intelligentsia (from Belinsky to Bunakov) were: the spirit of self-sacrifice, intense participation in political causes or political thought, intense sympathy for the underdog of any nationality, fanatical integrity, tragic inability to sink to compromise, true spirit of international responsibility...

But of course people who read Trotsky for information anent Russian culture cannot be expected to know all this. I have also a hunch that general idea that avant-garde literature and art were having a wonderful time under Lenin and Trotsky is mainly due to Eisenstadt films - "montage" - things like that - and great big drops of sweat rolling down rough cheeks. The fact that pre-Revolution Futurists joined the party has also contributed to the kind of (quite false) avant-garde atmosphere which the American intellectual associates with the Bolshevik Revolution.

I do not want to be personal, but here is how I explain your attitude: in the ardent period of life you and the other American intellectuals of the twenties regarded with enthusiasm and sympathy Lenin's regime which seemed to you from afar an exciting fulfillment of your progressive dreams. Quite possibly, had the position been reversed, Russian avant-garde young writers (living, say, in an Americoid Russia) would have regarded the burning of the White House with similar enthusiasm and sympathy. Your concept of pre-Soviet Russia, of her history and social development came to you through a pro-Soviet prism.

When later on (i.e., at a time coinciding with Stalin's ascension) improved information, a more mature judgment and the pressure of inescapable facts dampened your enthusiasm and dried your sympathy, you somehow did not bother to check you preconceived notions in regard to old Russia while, on the other hand, the glamor of Lenin's reign retained for you the emotional iridescence which your optimism, idealism and youth had provided.

What you now see as a change for the worse ("Stalinism") in the regime is really a change for the better in knowledge on your part. The thunderclap of administrative purges woke you up (something that the moans in Solovki or at the Lubianka had not been able to do) since they affected men on whose shoulders St. Lenin's hand had lain. You (or Dos Passos, or Rahv) will mention with horror the names of Ezhov and Yagoda - but what about Urtisky and Dzerzhinsky?

I am now going to state a few things which I think are true and which I don't think you can refute. Under the Tsars (despite the inept and barbarous character of their rule) a freedom-loving Russian had incomparably more possibility and means of expressing himself than at any time during Lenin's and Stalin's regime. He was protected by the law. There were fearless and independent judges in Russia. The Russian sud after the Alexander reforms was a magnificent institution, not only on paper. Periodicals of various tendencies and political parties of all possible kinds, legally or illegally, flourished and all parties were represented in the Dumas. Public opinion was always liberal and progressive.

Under the Soviets, from the very start, the only protection a dissenter could hope for was dependent on government whims, not laws. No parties except the one in power could exist. Your Alymovs are specters bobbing in the wake of a foreign tourist. Bureaucracy, a direct descendant of party discipline, took over immediately. Public opinion disintegrated. The intelligentsia ceased to exist. Any changes that took place between November 1919 and now have been changes in the decor which more or less screens an unchanging black abyss of oppression and terror.

I think I shall eventually polish this letter and publish it somewhere.

Yours,

V

Wilson admired Faulkner's Light in August, telling Nabokov he found it "remarkable." His correspondent could not agree.

November 21, 1948

Dear Bunny,

I have carefully read Faulkner's Light in August, which you so kindly sent me, and it has in no way altered the low (to put it mildly) opinion I have of his work and other (innumerable) books in the same strain. I detest these puffs of stale romanticism, coming all the way up from Marlinksy and V. Hugo - you remember the latter’s horrible combination of starkness and hyperbole - l’homme regardait le giblet, le giblet regardait l’homme.

Faulkner’s beloved romanticism and quite impossible biblical rumblings and “starkness” (which is not starkness at all but skeletonized triteness), and all the rest of the bombast seem to me so offensive that I can only explain his popularity in France by the fact that all her own popular writers (Malraux included) of recent years have also had their fling at l’homme marchait, la nuit etait sombre. The book you sent me is one of the tritest and most tedious examples of a trite and tedious genre. The plot and those extravagant “deep” conversations affect me as bad movies do, or the worst plays and stories of Lenid Adreyev, with whom Faulkner has a kind of fatal affinity.

I imagine that this kind of thing (white trash, velvety Negroes, those bloodhounds out of Uncle Tom’s Cabin melodramas, steadily baying through thousands of swampy books) may be necessary in a social sense, but it is not literature, just as the thousands of stories and novels about downtrodden peasants and fierce ispravniki in Russia, or mystical adventures with the narod (1850-1880), although socially effective and ethically admirable, were not literature. I simply cannot believe that you, with all your knowledge and taste, are not made to squirm by such things as the dialogues between the “positive” characters in Faulkner (and especially those absolutely ghastly italics). Do you not see that despite the difference in landscape, etc., it is essentially Jean Valjean stealing the candlesticks from the good man of God all over again? The villain is definitely Byronic. The book’s pseudo-religious rhythm I simply cannot stand - a phoney gloom which also spoils Mauriac’s work. Has la grace descended upon Faulkner too? Maybe you are just pulling my leg when you advise me to read him, or impotent Henry James or Rev. Eliot?

I am very much looking forward to our Russian book. We ought to plan the volume more definitely.

Sincerely yours

V

November 9, 1949

Dear Bunny,

I did not write you before my book (the autobiographic one) is taking a lot of my time. I was always told that Russian words had only one stress-accent. I am sure I also mentioned in the course of our correspondence that long English words tend to double the accent (though perhaps more so in American speech than in British). I don't see the point of the "-ion" affair, but anyway it is not unlike the change of -ie endings to -'e in corresponding Russian nouns, such as zhelanie to zhelan'e. Ponder this. We shall continue the discussion - of which I seem to be getting the better - when at last I come to you or you to me.

A story about my first love adventure is going to appear soon in the New Yorker, but another piece, on my student days, had to be withdrawn because they wanted me to revise certain passages (that readers might have found offensive or at least surprising) about Lenin and tsarist Russia. It is much the same kind of harmless stuff I once wrote you about Leninism, etc. Sad.

I have still about fifty pages of the book, and my little motor is running sweetly. I am afraid you will not care for the thing but I have to get it off my chest.

Down with Faulkner!

yours,

V

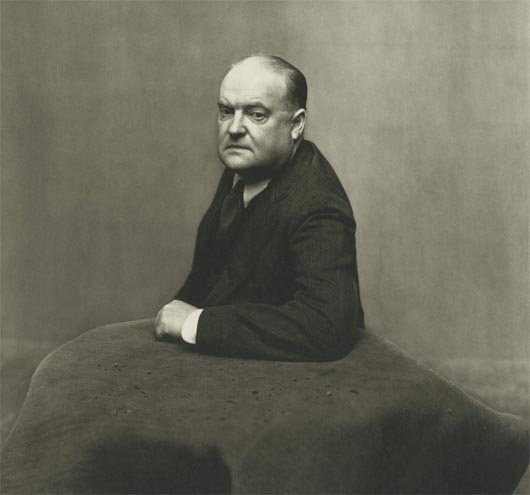

edmund wilson with mary mccarthAlthough they could not come to terms on their appreciation of Faulkner, Wilson attempted to sway Vladimir's opinion on other English language authors in this excerpt from a letter dated May 9, 1950. You can get a pretty specific idea of Wilson's view on women from the following:

edmund wilson with mary mccarthAlthough they could not come to terms on their appreciation of Faulkner, Wilson attempted to sway Vladimir's opinion on other English language authors in this excerpt from a letter dated May 9, 1950. You can get a pretty specific idea of Wilson's view on women from the following:

(3) I've just been examining the early text of Madame Bovary that was published last year. It is impressive and to me a little surprising to see how Flaubert worked. The most marvellous passages in the finished version are often quite flat in this one, and even rather inept. It is startling to see the distance (in the scene where Charles Bovary, as a boy, looks wistfully out the window at Rouen)... It is as if he first assembled his data and then at a given point turned on the music and magic. I am especially interested in this because it is more or less my own method. You, I imagine, are more likely to start with the words themselves.

(4) You are mistaken about Jane Austen. I think you ought to read Mansfield Park. Her greatness is due precisely to the fact that her attitude towards her work is like that of a man, that is, of an artist, and quite unlike that of the typical woman novelist, who exploits her feminine day-dreams. Jane Austen approaches her material in a very objective way. Each of her books is a study of a different type of woman, whom Jane Austen can see all around. She wants, not to express her longings, but to make something perfect that will stand. She is, in my opinion, one of the half-dozen greatest English writers (the others being Shakespeare, Milton, Swift, Keats and Dickens). Stevenson is second-rate. I don't know why you admire him so much - though he has done some rather fine short stories. I tried reading to Henry and Reuel a couple of summers ago one of the only books of Stevenson I had ever liked, The New Arabian Nights, but completely failed to interest them in it. It surprised me to find that these stories were the thinnest kind of verbalizing and that the characters had not even a fairy-tale existence. Sherlock Holmes, which we had just been reading and which was partly derived from The New Arabian Nights, seems a solid creation besides them. I didn't like Treasure Island even as a child.

EW

You can find more of Vladimir Nabokov on This Recording here.

"Redemption (ft. Robert Owens)" - Icicle (mp3)

"Nausea" - Icicle (mp3)

"Dreadnought (ft. SPMC)" - Icicle (mp3)

"Step Forward (ft. Robert Owens)" - Icicle (mp3)

Summer Reading

from Dayna Evans

from Kara VanderBijl

from Jane Hu

from Andrew Zornoza

from Barbara Galletly

from Dick Cheney

from Karina Wolf

from Alex Carnevale