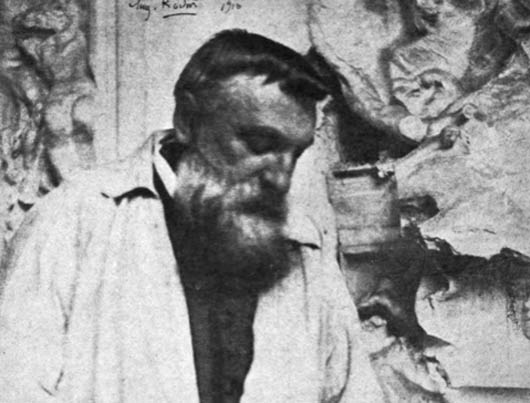

If Rodin had lived, today he would turn 172.

The Birdlike Ones

by ISABELLA YEAGER

Deeply affected by the loss of her infant daughter, René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke’s mother Phia dealt with parts of her grief by dressing her young son in girl’s clothing. As historian Ralph Freedman put it, "on one occasion when he was expecting to be punished the seven-year-old boy made himself into a girl to placate his mother. His long hair done up in braids, his sleeves rolled up to bare his thin, girlish arms, he appeared in his mother’s room. 'Ismene is staying with dear Mama,’ he is quoted as saying. ‘Rene is a no-good. I sent him away. Girls are after all so much nicer.'"

The connections between verse and a feminine sensibility were made uncomfortably explicit by Phia herself, who exposed her son to poetry before he was able to read. A catalog of vivid imagery and language accumulated in his mind, as his mother saturated his childhood with stories of saints’ lives, holy relics, religious art and ardent devotional rhetoric.

His parents separated in 1884. After their divorce they insisted Rilke attend a military academy, which he left in poor health. He wrote,

Someone will tell a story of a child that often forgot to eat because it seemed more important to him to carve cheap wood with a cheap knife, and someone will relate some event of the days of early manhood that contained promise of future greatness – one of those incidents that are intimate and prophetic.

He was accepted into university and studied literature, art history, and philosophy in Prague and Munich, where he met and fell in love with the sophisticated, articulate and married Lou Andreas-Salome, at whose urging he had his name changed from Rene to what she considered to be the more masculine "Rainer." Rilke traveled with Salome and her husband Friedrich Andreas into Eastern Europe, Bohemia, and Russia.

In 1900 Rilke visited the artists’ colony Worpswede, where he met and wed sculptor Clara Westhoff. The couple’s child Ruth was born at Worpswede, but a year later Rilke traveled to Paris to begin his treatise on Auguste Rodin, to whom he acted as secretary. While in Paris he lived adjacent to Rodin at 77 Rue de Varenne, in the old mansion surrounded by a park which is now the Musee de Rodin. Clara followed soon after, leaving their daughter with her parents. Their efforts at divorce in the coming years were thwarted by the technicalities of Catholicism.

Rilke’s writing on Rodin begins,

It is a life that has lost nothing and has forgotten nothing; a life that has absorbed all things as it passed, for only out of a life such as this, we believe, could have risen such fulness and abundance of work; only such a life as this, in which everything is simultaneous and awake, in which nothing passes unnoticed, could remain young and strong and rise again to such high creations.

Rodin in 1910

Rodin in 1910

Auguste Rodin was the son of a police department clerk. In his school years, his drawing teacher believed that in order to encourage his students to draw from recollection and with independent vision, the personality should be developed and encouraged before artistic instruction began. Rodin’s sister Maria died of peritonitis, an abdominal infection caused by rupture to a hollow organ, and exacerbated by the flexing of the hips. Rodin was wracked by guilt at the possibility that the suitor to whom he had introduced Maria had been unfaithful.

Consistently denied access to Parisian art academies, Rodin spent his early career earning a living as a craftsman and an architectural ornamenter. Rodin’s sense of interior and surface evolved during the course of his work with goldsmith and animal sculptor Antoine-Louis Bayre, a fine worker in musculature and movement.

The Crying Lion, 1881

The Crying Lion, 1881

Of animals rendered in stone, Rilke writes:

There were small figures, animals particularly, that moved, stretched or curled; and although a bird perched quietly, it contained the element of flight. …There was stillness in the stunted animals that stood to support the cornices of the cathedrals or cowered and cringed beneath the consoles, too inert to bear the weight; and there were dogs and squirrels, wood-peckers and lizards, tortoises, rats and snakes.

Other animals could be found that were born in this petrified environment, without remembrance of a former existence. They were entirely the natives of this erect, rising, steeply ascending world. Over skeleton-like arches they stood in their fanatic meagerness, with mouths open, like those of pigeons; shrieking, for the nearness of the bells had destroyed their hearing. They did not bear their weight where they stood, but stretched themselves and thus helped the stones to rise. The birdlike ones were perched high up on the balustrades, as though they were on their way to other climes, and wanted but to rest a few centuries and look down upon the growing city. Others in the form of dogs were suspended horizontally from the eaves, high up in the air, ready to throw the rainwater out of their jaws that were swollen from vomiting. All had transformed and accommodated themselves to this environment; they had lost nothing of life.

Rilke has that innate consciousness of internal structure, of the rigid constraints that provide so much of the impetus for creativity, that play a key role in a poet’s work. It is easy to see how his understanding of rhyme might lend itself to that of a gargoyle: of both as ornamental and architecturally functional.

His muscular prose has no trouble conveying the immense energy contained within these stone creatures, whose appearance is that of halted motion – in physics, of potential. Words regarding Rodin’s later piece Illusion, the Daughter of Ikarus also call to attention the motion found here, this time in bronze and in human form, calling her that dazzling embodiment of a long, helpless fall.

Rodin called Rilke’s finished book, Auguste Rodin, the definitive interpretation of his work. Rilke’s writing on the sculptor is in its essence an act of translation: from visual to written, from one artist to another. It is unsurprising that to Rilke, who wrote with equal ease in his native German and in French, translation came naturally.

The task of the translator is a weighty one: he is bound inextricably by several opposing responsibilities. As only a creative mind is able, he must somehow see past the gleam of the finished product to discern the masonry beneath, and in retracing these steps seek to follow them himself. But translation as a creative effort gives little creative license: the translator has to understand that the tool he uses is not his own; that in his case creativity serves only to aid in the production of a loyal representation of an original. In short, the translator must look deeply into the polished surface of a work without pausing at his own reflection.

The act of translating is a process marked by its tenuous balance between dutiful distance and moments of measured emotional release, at once intimate and bound by the most formal kind of duty and restraint. One must seek, find, and convey something without for a moment claiming it; one must break apart and reconstruct but leave no mark or signature. One must hold with no intention to own.

At that time the war came and Rodin went to Brussels. He modeled some figures for private houses and several of the groups on top of the Bourse, and also the four large corner figures on the monument erected to Loos, City-mayor in the Parc d’Anvers. These were orders which he carried out conscientiously, without allowing his growing personality to speak. His real development took place outside of this; it was compressed into the free hours of the evening and unfolded itself in the solitary stillness of the nights; and he had to bear this division of his energy for years.

Beginning in 1870, Rodin’s work sat in his workshop, unseen, as he was unable to afford castings. His submissions of models to competitions for sculpture commissions failed but on his own time he began work on St. John the Baptist Preaching.

And we have that “John” with the eloquent, agitated arms, with the great stride of one who feels another coming after him. This man’s body is not untested: the fires of the desert have scorched him, hunger has racked him, thirst of every kind has tried him. He has come through all and is hardened. The lean, ascetic body is like a wooden handle in which is set the wide fork of the stride. He advances, advances as though all the wide spaces of the world were within him, as if he were apportioning them with his stride. He advances. His arms express it, his fingers are widespread, seeming to make the sign of striding forward in the air. This “John” is the first pedestrian figure in Rodin’s work. Many follow.

We recall John later on, when Rilke outlines Rodin’s progression from master of the face to master of the body, of the gesture, of surface, and of the step.

When Rodin won the 1880 commission to build a portal for a museum of decorative arts, he begun what were to be four decades of work on Gates of Hell. The museum remained unbuilt and the gates themselves unfinished, but several of the work’s more famous elements include the now-ubiquitous The Thinker and The Kiss.

Implicit in Rilke’s exploration of Rodin as a reader is the sense that literature and art have a natural relationship and in many cases can share a vocabulary. At times he wrote of literature’s direct, emotional effect on Rodin:

He read for the first time Dante’s Divina Comedia. It was a revelation. The suffering bodies of another generation passed before him. He gazed into a century the garments of which had been torn off; he saw the great and never-to-be-forgotten judgment of a poet on his age. There were pictures that justified him in his ideas; when he read about the weeping feet of Nicholas the Third, he realized that there were such feet, that there was a weeping which was everywhere, over the whole of mankind, and that there were tears that came from all pores.

At others, he used the vocabulary of plastic arts to illustrate the relationship between sculpture and writing, and the ability of one to communicate the sense of the other:

He gave reality to all the figures and forms of Dante’s dream, lifted them as it were from the stirred depths of his own memory and gave to each in turn the silent deliverance of material existence. Hundreds of figures and groups were thus created. But the movements, which he found in the words of the poet, belonged to another age; they awoke in the creative artist, who restored them to life, the knowledge of thousands of other movements, gestures of appropriation, of loss, of suffering and of resignation which had been evolved in the intervening years, and his tireless hands went on and on beyond the world of the Florentine poet to ever new gestures and figures.

From Dante he came to Baudelaire. …In this poet’s verses there were passages, standing out prominently, that did not seem to have been written but moulded; words and groups of words that had melted under the glowing touch of the poet; lines that were like reliefs and sonnets that carried like columns with interlaced capitals the burden of a cumulating thought. He felt dimly that this poetic art, where it ended abruptly, bordered on the beginning of another art and that it reached out toward this other art. In Baudelaire he felt the artist who had preceded him, who had not allowed himself to be deluded by faces but who sought bodies in which life was greater, more cruel and more restless...

Later, when as a creator he again touched those realms, their forms rose like memories in his own life, aching and real, and entered into his work as though into a home.

It seems effortless for the poet to understand the way that words might so energetically produce images and shapes in the mind of the sculptor, perhaps because as a writer his mastery is in putting shape and object to words.

isabelle adjani & gerard depardieu in "Camille Claudel"

isabelle adjani & gerard depardieu in "Camille Claudel"

Rilke recalls how Rodin’s maturation as an artist followed a series of revelations he experienced as to the nature of surface, of body and of the relationship of the conceptual to the physical. These developments took place around the same time as his drama-filled affair with sculptor and graphic artist Camille Claudel.

While he was working on the Exchange of Brussels, he may have felt that there were no more buildings which admitted of the worth of sculpture as the cathedrals had done, those great magnets of plastic art of past times. Sculpture was a separate thing, as was the easel picture, but it did not require a wall like the picture. It did not even need a roof. It was an object that could exist for itself alone, and it was well to give it entirely the character of a complete thing about which one could walk, and which one could look at from all sides. And yet it had to distinguish itself somehow from other things, the ordinary things which everyone could touch.

And further,

It must be intercalated in the silent continuance of space and its great laws. It had to be fitted into the space that surrounded it, as into a niche; its certainty, steadiness and loftiness did not spring from its significance but from its harmonious adjustment to its environment.

Of the Danaide, Rilke praises spatial presence: flinging herself from a kneeling position into her flowing hair… it is wonderful to pass slowly round this marble, to follow the long, long way which passes from the full, rich curve of the back to the face losing itself in the stone as if in a great weeping….

He goes on to expand upon Rodin’s development of the body as a medium and as a vehicle to and from ideas.

Rodin knew that, first of all, sculpture depended upon an infallible knowledge of the human body. … Rodin had now discovered the fundamental element of his art;…it was the surface,– this differently great surface, variedly accentuated, accurately measured, out of which everything must rise,– which was from this moment the subject matter of his art. … His art was not built upon a great idea, but upon a minute, conscientious realization, upon the attainable, upon a craft. …With this awakening Rodin’s most individual work began.

The public’s disdain at Rodin’s early work reflected a culture that, in Rilke’s words,

held to the superficial, cheap and comfortable metier that was satisfied with the more or less skillful repetition of some sanctified appeal. In this environment the head of The Man with the Broken Nose should have roused the storm that did not break out until the occasion of some of the later works of Rodin.

This face had not been touched by life, it had been permeated through and through with it as though an inexorable hand had thrust it into fate and held it there as in the whirlpool of a washing, gnawing torrent.

When one holds and turns this mask in the hand, one is surprised at the continuous change of profiles, none of which is incidental, imagined or indefinite. There is on this head no line, no exaggeration, no contour that Rodin has not seen and willed. One feels that some of the wrinkles came early, others later, that between this and that deep furrow lie years, terrible years.

But this beauty is not the result of the incomparable technique alone. It rises from the feeling of balance and equilibrium in all these moving surfaces, from the knowledge that all these moments of emotion originate and come to an end in the thing itself.

However great the movement of a sculpture may be, though it spring out of infinite distances, even from the depths of the sky, it must return to itself, the great circle must complete itself, the circle of solitude that encloses a work of art. This is the law which, unwritten, lived in the sculptures of times gone by. Rodin recognized it; he knew that that which gave distinction to a plastic work of art was its complete self-absorption. It must not demand nor expect aught from outside, it should refer to nothing that lay beyond it, see nothing that was not within itself; its environment must lie within its own boundaries.

rodin in 1862, photograph by charles aubryUnlike a portrait, which as children freaked us out because its eyes always seemed to meet our gaze, "the sculptor Leonardo has given to Gioconda that unapproachableness, that movement that turns inward, that look which one cannot catch or meet." Rodin’s studies of the body, of a surface "with infinitely many movements," reflected his new commitment to his medium and to craft, and produced two of his most famous pieces and nods to literary influence, Monument to Victor Hugo and Balzac.

rodin in 1862, photograph by charles aubryUnlike a portrait, which as children freaked us out because its eyes always seemed to meet our gaze, "the sculptor Leonardo has given to Gioconda that unapproachableness, that movement that turns inward, that look which one cannot catch or meet." Rodin’s studies of the body, of a surface "with infinitely many movements," reflected his new commitment to his medium and to craft, and produced two of his most famous pieces and nods to literary influence, Monument to Victor Hugo and Balzac.

In response to the former, the Times observed in 1909 that "there is some show of reason in the complaint that his conceptions are sometimes unsuited to his medium, and that in such cases they overstrain his vast technical powers." The latter was panned with “there may come a time, and doubtless will come a time, when it will not seem outre to represent a great novelist as a huge comic mask crowning a bathrobe, but even at the present day this statue impresses one as slang."

Monet and Debussy, on the other hand, signed a manifesto in its defense. Rilke too was into it: if The Man With the Broken Nose was proof of Rodin’s mastery of the face, he writes, The Man of Early Times had shown his adeptness at the body and the entry of gesture into Rodin’s work; of John and The Burghers of Calais – with their lean, rough musculature and strikingly directed movement: "setting out on their grievous journey – …all his walking figures seem to be but a preparation for the great, challenging step of Balzac."

Rilke had a rough time in Paris at first. His exposure to and fascination with Rodin’s work eventually contributed to a stylistic overhaul in his poetry. The man who once wrote a short book of letters to God with stunning if intangible subject matter (The Book of Hours) turned now to ideas as concrete as to be titled The Book of Images, and finally, simply, New Poems in 1907. These gemlike poems each stemmed from a discrete idea or image, and yielded markedly physical, visual, and aesthetic works. "The Panther" deals with the gaze, with supple movement and occupation of space, with musculature, physicality, and emotion.

Strong and supple strides around

and back to their beginning come.

A swirling play of power surrounds

a noble will that stands there numb.

This could almost be a continuation of Rilke’s writing on sculpture. In it there are the elements of life; of endurance; of physical representation of self that he alludes to when describing the impossibly lifelike lines etched in face of The Man With the Broken Nose.

But it is in "Morgue" that Rilke outdoes himself, subtly but definitely, in creating a poem whose nuance is so great, its allusions to creator and created, of seer and seen, of captured life so complex, that it seems inevitable to compare it to a finely-wrought object, a gesture, a step.

They lie here ready, as if we ought to find

a mission for them — something they’d be told

was urgent, which might reconcile and bind

them to each other, even to the cold:

An invitation to a final club,

an unexpected scrap of paper found

in one of their pockets. The bored look around

their mouths, which someone gave a rub,

did not come off, but just got very clean.

Their beards are waxy, stiffer on the chin,

trimly agreeing with the warden’s taste.

He wants us to appreciate the scene.

Beneath the lids, their sight has been replaced

with rolled-back eyes that dwell on things within.

Isabella Yeager is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She twitters here and tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about a foreshadowing of death.

"Bye Bye Bye" - School of Seven Bells (mp3)

"Babelonia" - School of Seven Bells (mp3)