The Woman

by ALEX CARNEVALE

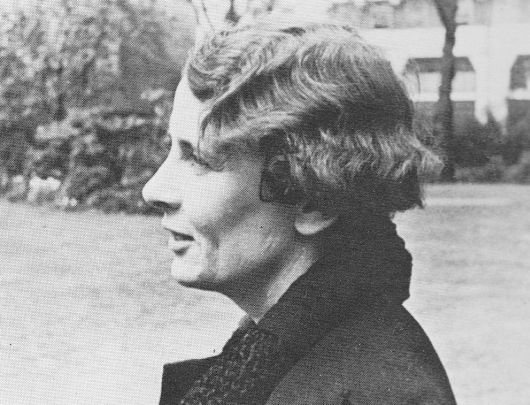

I wonder if we are all wrong about each other, if we are just composing unwritten novels about the people we meet.

Rebecca West, 1920

The girl born Cissie Fairfield chose the name Rebecca West. She grew up in London's largest Jewish neighborhood, and by selecting an ethnic first name, she gave herself something of what was obvious in those that surrounded her. The handle itself was taken from Ibsen's Rosmerholm, where Rebecca West is the adulteress who persuades her married lover to join her in a double suicide.

Like regretting a particularly egregious tattoo, she turned on Mr. Ibsen shortly thereafter, writing "I began to realize Ibsen cried out for ideas for the same reason men cry out for water: because he had not got any."

She was hired as assistant editor at The Freewoman, an early British feminist weekly. She quickly grew tired of the paper's narrow focus on politics. She did not like criticizing women who were ostensibly part of the cause; she viewed herself as a kind of Mark Twain who destroyed ignorance by stabbing it slyly in the back, not by attacking from the front.

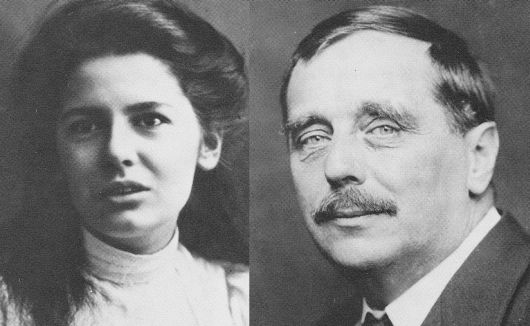

Rebecca and H.G. Wells

Rebecca and H.G. Wells

She also left The Freewoman for an unrelated reason: love. H.G. Wells read her review of his novel Marriage in the paper. Wells, 45, was already on his second marriage, and deeply unsatisfied sexually. His wife Jane knew of his numerous affairs, mostly with other writers with which he came in contact. He described his latest infautuation as having "a fine dark brow and dark, expressive, troubled eyes. I had never met anyone quite like her before, and I doubt if there was ever anyone like her before."

In another way, Rebecca's idiosyncrasies frightened him, and Wells could depend upon a more reliable mistress. Rebecca did not take the initial rejection kindly. (He gave her the slow fade, going abroad with his girlfriend after their first meetings.) She wrote to him, "During the next few days I shall either put a bullet through my head or commit something more shattering to myself than death."

It was Rebecca's writing that brought them together again, especially her travel articles about France and Spain. He admired them, and he should have: she was, at a precociously young age, his equal with the pen. She waited a few weeks before having sex with him. It could not have come as much of a surprise when she found herself pregnant.

Their romance was not dimmed by this relevation at first. Role-playing quickly became their most amusing pastimes: she called him Jaguar and she referred to him as Panther, perhaps because of his speed. The two set up an elaborate sexual interchange that excited Wells to no end, and he forgot about his last affair in favor of the new.

Wells wrote, "Panther I love you as I have never loved anyone. I love you like a first love. I give myself to you. I am glad beyond any gladness that we are to have a child." They named the boy Anthony Panther, a choice which would disgust a generation of scholars. H.G. himself was absent for the birth.

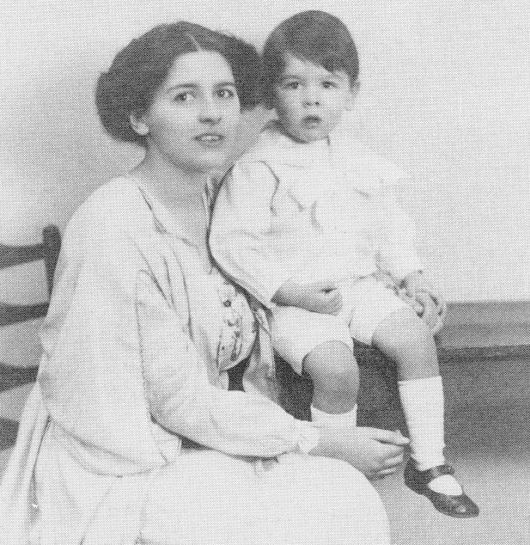

Anthony and Rebecca

Anthony and Rebecca

Their relationship could not help but grow more complicated. The last thing Wells wanted was a family life with his girlfriend - that wasn't what was missing from his life. He wanted her to make time with female friends, and pop up whenever he needed a fuck.

Wells hid Rebecca in an isolated suburb of London. Out of boredom and frustration, she wrote her first book, a tearing down of Henry James that met with Wells' approval. She loved her son dearly, but wished for a freedom impossible for a young mother. Adding insult to injury, she was not acknowledged as the child's mother in her own home.

As soon as she could, she sent four-year old Anthony to boarding school. Wells loathed her for this decision. She wrote him to explain, saying, "I hate being encumbered with a little boy and a nurse, and being helpful. I hate waiting about." As Rebecca's behavior drifted farther and farther away from what Wells desired of her, he started having regular intercourse with Margaret Sanger.

Whereas before Rebecca had been represented in his novels as a pleasant free spirit, now she was as disturbed in his fiction as he perceived her to be in life, replete with the medical problems that troubled Rebecca all her days. The only thing worse than how Wells treated women were his ghastly political views.

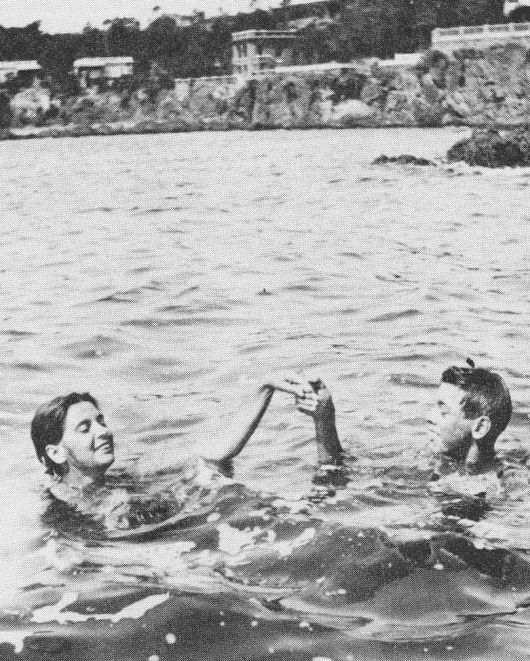

Anthony and Rebecca swimming

Anthony and Rebecca swimming

By the age of six Anthony Panther still could not read. Rebecca's slow pulling away from Wells' hold over her was the only thing that kept his interest alive. "I've not kept faith," he wrote her. "I've almost tried to lose you. You are probably the only person who can really give me love and make me love back. And because you've been ill I've treated you so's I've got no right to you any more. Have I ever got into your arms to cry? I would like to do that now."

She had the trick of drawing all sorts of people to her, women and men, but especially writers. Her meeting with D.H. Lawrence invigorated a desire to focus on her work, and her next novels were a leap ahead from all she had produced before. Stylistically and emotionally, she was pulling away from Wells' grip on her, and towards a fiction influenced by the modernists who were her peers instead of the generation moving into old age and death. After he read her novel The Judge, he wrote, "She splashed her colours about; she exalted James Joyce and D.H. Lawrence, as if in defiance of me - and in despite of Jane and everything trim, cool and deliberate in the world."

Her admirer W. Somerset Maugham's letter had a different theme: "I do not think there is anyone writing now who can hold a candle to you."

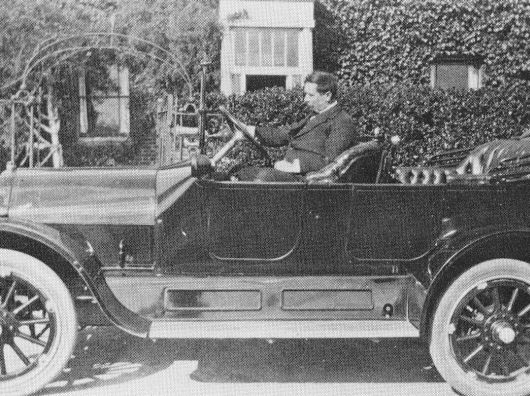

wells in his auto

wells in his auto

It was this sort of affirmation which allowed her to give H.G. Wells a final ultimatum - marriage or separation. He was insulted by the idea he would have to choose between her and his wife. Eventually, after Wells unexpectedly showed up during a retreat at Marienbad she planned with a few friends, Rebecca gave him up. She sailed to America in a geographical severance. It was her first time in our country. How they worshipped her here!

West was in New York only a few weeks before Charlie Chaplin began making aggressive advances on her person. The gossip that had spread about her strange arrangements in London only excited her new American friends, with one crowing, "We fell in love with you, you know. And if you are so fascinating when you are living through a tragedy, you must be dangerous indeed now that it is over."

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He is a writer living in Manhattan. He tumbls here and twitters here. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here.

"Thorn in My Side" - Veronica Falls (mp3)

"Eighteen Is Over The Hill" - Veronica Falls (mp3)

1982

1982