Our Actual Life

by ALICE BOLIN

21 Jump Street

dir. Phil Lord & Chris Miller

109 minutes

Phil Lord and Chris Miller’s remake of 21 Jump Street begins with a large title reading “YEAR 2005,” and Morton Schmidt (Jonah Hill) appears dressed in a style that has not been lampooned enough: peroxide blond Caesar haircut, white t-shirt, preposterous baggy jeans. It earns Schmidt the nickname “Not-So-Slim Shady,” and he is a dead ringer for that kid — every mid-2000s student body had someone who looked exactly like him. Just the sight of him in this get-up makes for its own comedic beat, but the humor catches us off guard — how could a look that was so ubiquitous to high school campuses and 7-11s seven years ago be so absurd now, such an easy laugh? Was 2005 really that long ago?

The point of 21 Jump Street is that it was a long time ago, and all the rules — of going to high school, or making a movie, or making a movie about high school — have changed since then. Schmidt and his partner Greg Jenko (Channing Tatum) are undercover cops assigned to investigate the manufacture and distribution of a mysterious hallucinogenic drug at a high school, and they learn that the social order is not so clear-cut as when they were in school. Back in ’05, Jenko was a jock who made fun of the nerdy Schmidt, but this binary of cool and uncool doesn’t apply in the same way at the school they’re infiltrating. And what a relief that is for the film’s audience — who could possibly be interested in that dynamic anymore?

The cool kids at their new school are crunchy and progressive, led by Eric (Dave Franco), who was accepted to Berkeley “early admish” and has a biodiesel Mercedes that runs on left over grease from Hunan Palace. He tells Schmidt that he and his girlfriend are not exclusive — “I just don’t believe in possession, jah feel?” — and plays a song about Mother Earth on his acoustic guitar. Schmidt, once a member of his high school’s Juggling Society, is thrilled at how the tables have turned, as he catalogs with wonder the things that are now considered cool: liking comic books, environmental awareness, being tolerant. Former jock Jenko is not so excited. “Organized sports are so fascist. It makes me sick!” Eric yells after a track meet. “I don’t get this school,” Jenko says.

Jenko claims to know why high school has changed: Glee. “Fuck you, Glee!” he yells in the lunchroom. But we may see this more broadly as part of Judd Apatow’s late-2000s loser coup, a real life revenge of the nerds that we ultimately have to thank for the phrase “Academy Award Nominee Jonah Hill.” This shift is an important reason why 2005 is so distant: the string of films Apatow produced in 2007 and 2008 revolutionized the stoner comedy, the high school comedy, and the buddy comedy. It’s Apatow’s classic but short-lived Freaks and Geeks, resurrected and taking revenge on the network suits who didn’t get it, with Knocked Up and Pineapple Express (freaks) and Superbad (geeks) reclaiming things for themselves.

A key feature of these Apatow productions is the study in male best friendship. As with all depictions of close male companionship, there is an element of the homoerotic (Frodo and Sam, hi), but in the bromance, it is not read indirectly, with sexual tension permeating through the friends’ brooding or aggression. It is not properly a subtext at all — bromance relationships are overtly tender, and how gay they are for each other is, you know, the joke.

With Jenko and Schmidt, it’s true love: they strap gun holsters under their ivory tuxedoes as they prepare to take down the drug dealers once and for all at the prom. “Jenko,” Schmidt says, looking over at him. “Will you go to prom with me?” At the end of the film, Jenko jumps in front of Schmidt and takes a bullet in the shoulder. Schmidt leans over him on the ground and says sweetly, “I fucking cherish you.” After they are forced to take the mystery drug at school, they run to the bathroom, desperate to throw it up. Their attempt to purge each other, sticking their fingers in each other’s mouths and making loud choking groans, is kinky as hell.

Where 21 Jump Street succeeds is in applying new conventions to old genres. This is a reboot, after all. Nick Offerman makes a hilarious cameo as the gruff captain who assigns them to the undercover division. They are reviving an old undercover program from the ‘80s, he tells them — “The guys in charge of this stuff have no creativity or imagination. All they do now is recycle shit from the past and expect us all not to notice.” The filmmakers seem aware of how silly remaking 21 Jump Street is — they share the reservations that have made reviewers and audiences unable to report that the movie is good without employing the word “actually.” “Report to Jump Street,” Offerman tells Jenko and Schmidt meaningfully. “37 Jump Street… No that doesn’t sound right.”

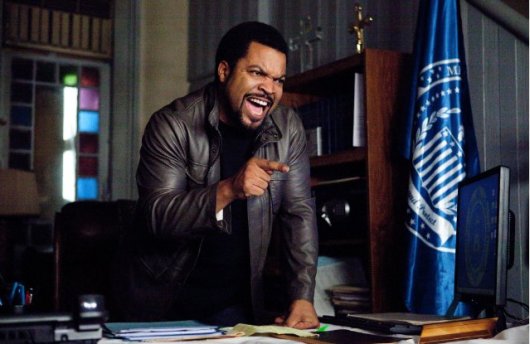

Ice Cube portrays the head of Jump Street, Captain Dickman (in the tradition of Ice-T, a once terrifying gangster rapper playing a police officer. Rappers get irony.), who describes himself as the stereotypical angry black captain. “Embrace your stereotypes,” he advises the future undercover officers. In some ways, the film employs this advice, taking the path of least opposites-attract comedy resistance. There is the standard training montage as Jenko and Schmidt go through the police academy, with brainy Schmidt helping Jenko with his exams, and sporty Jenko helping Schmidt with the physical requirements. Each has what the other lacks — it is the movie’s prevailing cliché. At the end of the film, Jenko describes what he has learned about covalent bonds in chemistry class. “It’s when atoms share electrons,” he explains. “They both need what the other has, and that makes them stick together.”

In other cases, though, expected tropes are played with and subverted. Ellie Kemper plays the chemistry teacher who is instantly, ravenously taken with Jenko. Her deranged advances are scene stealing, but she figures into the movie’s plot almost not at all. It is as if she exists simply because a horny teacher is something that would exist in a high school movie — even if it’s a trope that the filmmakers ultimately decide not to make use of. Other characters are comically under-used — the other officers in the Jump Street division, played by Rye Rye and Dakota Johnson, are shown from time to time wearing cheerleading or marching band uniforms and bragging about the cases they’ve closed, seemingly as effective at their jobs as Schmidt and Jenko are inept. We get the feeling that there is any number of possible storylines, that a lot of the action is happening just off-screen.

It turns out that 21 Jump Street is ideal for the tongue-in-cheek remake, as it was both a high school drama and a police procedural — two genres that are ripe for parody. But the crime fighting in the film seems less influenced by 21 Jump Street than the maverick cops in Die Hard, a franchise that envisioned police officers who said the word “motherfucker” more than any had before. The main bad guys in 21 Jump Street are a gang of motorcycling drug dealers with face tattoos, and they aren’t really sources of comedy — they are straightforwardly terrifying. As the film takes a turn for the graphically violent toward the end, there is another layer of genre that the filmmakers are referring to and reckoning with: the action film.

These different genre elements mingle and combust. In the final shoot-out at a hotel room during the prom, two members of the motorcycle gang reveal themselves to be undercover DEA agents — played by Johnny Depp and his former 21 Jump Street cast-mate Peter DeLuise. Depp’s character yells at Schmidt and Jenko for ruining the DEA investigation. “We had no idea,” Schmidt apologizes. “You’re an amazing actor, man.” Schmidt and Jenko reveal that they’re in the Jump Street division, forging a camaraderie with Depp’s and DeLuise. “You know we were actually Jump Street?” Depp’s character asks. All this self-consciousness is too much and Depp and Grieco are both shot to death during this banter. It is an inevitable and perversely satisfying consequence of taking on so many influences: the features of one genre will not allow for the features of another.

At one point, Jenko and Schmidt are in a car chase with the drug dealers, and they shoot holes in an oil tanker and a truck carrying cans of propane. In both cases, they’re amazed that the truck does not blow up — ultimately it’s a collision with a chicken truck that causes the explosion. This dynamic, of the explosions they anticipate versus the one they actually get, speaks to the careful game of expectations. It’s a kind of gentle parody: if they are poking fun at the conventions of genre, it is as admiring as it is critical. “We’re like in the end of Die Hard right now, but it’s our actual life,” Schmidt says to Jenko after their final triumph over the bad guys. In the end, there’s something remarkably hopeful about 21 Jump Street — that a comedy can use the best parts of Die Hard and leave the rest. That high school can be something more than jocks and nerds, and a high school movie can be too.

Alice Bolin is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Missoula. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here and twitters here. She last wrote in these pages about Anna Pavlova.

"The Chamber & the Valves" - Dry the River (mp3)

"Weights & Measures" - Dry the River (mp3)