Forms of Taking It All

by ELLEN COPPERFIELD

They called it the slipper club. All of the photographer Dorothea Lange's friends were Jews; exiled for a second time from the mostly gentile areas of Nob, Russian, and Telegraph Hills in San Francisco to Pacific Heights. Lange was not herself among the chosen people, but all her friends were. They were as far from the immigrant Jews in the Fillmore as they were from the gentiles in the wealthier neighborhoods. The slipper club, so named because Dorothea gave all her closest ones footwear as a gift, met outside the circles of power due to the vagaries of a parlor anti-Semitism. They talked of gardening, the arts, their relationships.... It was through these people that Dorothea met the artist who would become her first husband, Maynard Dixon.

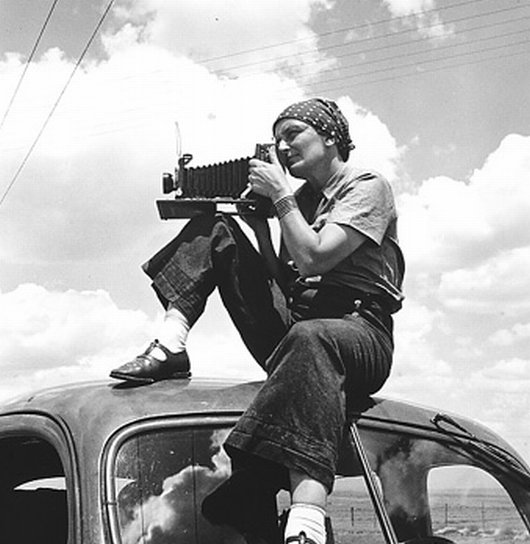

Dorothea Lange, 26, featured a high pitched voice and walked with a limp. She made her living from portrait photography. She set a price and never haggled over it; no one quibbled with the results. For example:

from 1932

from 1932

Maynard Dixon, 45, worked a pot-smoking illustrator whose sketches were featured in magazines with great frequency. His typical day involved waking up in the afternoon, getting high, and sampling the best of San Francisco's world cuisine. After the earthquake of 1906, he and his friends perserved in their lifestyle, almost amongst the rubble. Their neighborhood was called the Monkey Block, and it was razed in 1959 to build the TransAmerica Pyramid. Nobody was in a position to complain by then.

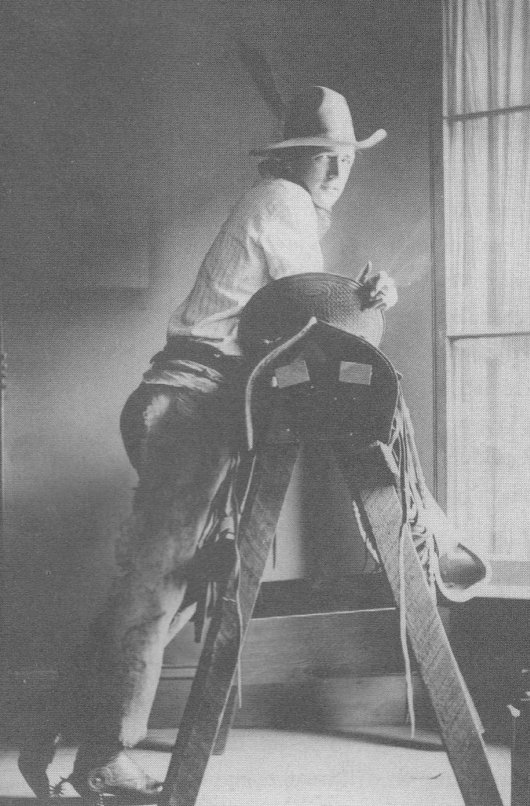

Maynard showed Dorothea the "real" California. He loved wide open spaces, and his representations of Arizona and New Mexico during the period remain quite captivating. She was immediately attracted to his cowboy good looks, his way around children. Her own concept of style always accentuated her natural beauty and minimized her defects. Despite her infirmity, brought on by a childhood bout of polio, she could hike and picnic, dragging her right leg on the ground when she was tired. The only thing she could not do was run.

the happy couple

the happy couple

They were married in her studio in March of 1920. He wore a cape, a black Stetson and wielded a carved swordcane with a stiletto. Their marriage invigorated his artistic career; he completed 140 paintings during the first five years of matrimony, and his reputation as a talented muralist at first grew and grew. The fact that he was nearing 50 as she approached 30, initially a source of Dorothea's apprehension, did not seem to matter a whit.

While others viewed Dorothea as a strong-willed entrepreneur, she did not mind how Maynard saw her — as a gorgeous young flower, a precious thing that could not be corrupted, but one had to try. This did not stop him from cheating on her with other women, often on long trips to the California wilderness he loved. Yet part of the reason the relationship sustained despite Maynard's imperfections was the fact the two kept their own lives.

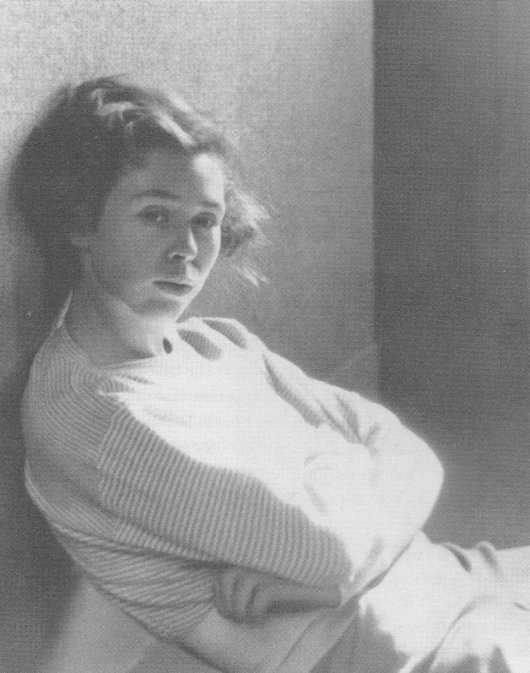

Maynard Dixon

Maynard Dixon

Near the end of her life she said of him, "Maynard was a restaurant man, a raconteur, a striking personality, graceful, had style, wit and originality. Much of the wit was defensive. Women loved him." Despite his considerable flaws, she viewed her new husband as an incandescent flame, and was most taken aback when his 12 year old daughter Consie Dixon came to live with them.

As a young child, Consie had been mistreated by her mother. At her stepdaughter's age, Dorothea stood out as helpful, kind and resourceful. In contrast Consie resisted her every directive, and found Dorothea's obsessiveness over her home frightening. (In later years, Dorothea would drop her sons in foster care while she travelled with Maynard and her second husband, Paul Taylor.) Maynard simply expected his new wife to care for the girl, who else would do it? To fill the hours with Consie, Dorothea began taking her picture. It looked like this:

consie dixon circa 1920

consie dixon circa 1920

In light of the fact a child already lived in their home, Maynard and Dorothea used birth control with alacrity. By the age of 29, she decided it was time to have a child of her own, and she gave Maynard two sons. Tensions with Consie temporarily abated when the girl got a job as a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner days after she turned 19. It was the onset of the Depression that would ultimately lose Consie that job and destroy her father's marriage.

Maynard's latent anti-Semitism had driven away most of his patrons, and when the art market in San Francisco collapsed, he could no longer sell his murals to anyone. After losing her job, Consie moved to Taos, New Mexico, and encouraged her parents to follow. Trouble quickly emerged in their new landing spot — neither Maynard or Dorothea had any idea how to drive a car. Maynard broke his jaw flipping over the family's first vehicle.

Taos, New Mexico

Taos, New Mexico

Even after that, Maynard tolerated the wide-open spaces of Taos far better than his wife. Dorothea had lost her clientele, her footwear association and the city she loved. The husband noticed none of his wife's unhappiness, and even after agreeing to a move back to San Francisco, the marriage would only last three more years. Dorothea observed in a profile of the family published in the San Francisco News that "an artist's wife accepts the fact that she has to contend with many things that other wives do not." She had her friends again.

Ellen Copperfield is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in San Francisco. She last wrote in these pages about Marlon Brando. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"Fame" - Santigold (mp3)

"God From The Machine" - Santigold (mp3)

The new album from Santigold is entitled The Master of My Make-Believe and it will be released on May 1st.