How's Your Hobbit?

by ALEX CARNEVALE

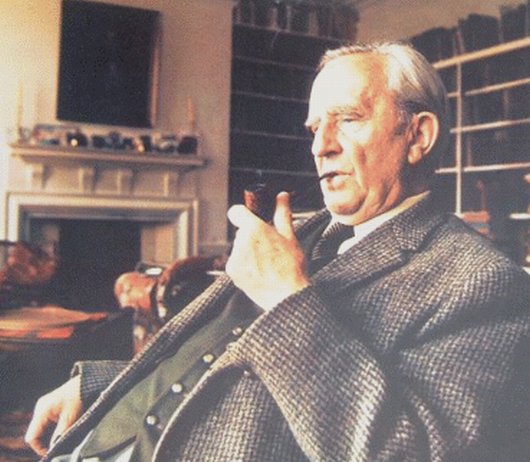

I first tried to write a story when I was about seven. It was about a dragon. My mother said nothing about the dragon but pointed out that one could not say "a green great dragon" but had to say "a great green dragon." I wondered why, and still do. The fact that I remember this is possibly significant, as I do not think I ever tried to write a story again for many years, and was taken up with language.

- J.R.R. Tolkien in a letter to W.H. Auden

After publishing The Hobbit in September of 1937, J.R.R. Tolkien worried about the direction his readers wanted him to take next. His book for young adults had been a success by any measure, and readers demanded more about Bilbo and company. His publisher Stanley Unwin informed him that everyone would be "clamoring next year to hear from you about Hobbits." Tolkien wrote back, "I am a little perturbed. I cannot think of anything more to say about hobbits." Later he exploded, "I am constantly asked how my hobbit is!"

Had Tolkien felt free to pursue his own interests (he had many varied ones) instead of giving into this pressure, he may not have spent the better part of the next two decades writing The Lord of the Rings, and may have imagined a litany of other worlds. As it is, Tolkien eventually gave in and told his publisher that "a sequel or successor to The Hobbit is called for" - and Middle Earth was born. Starting something new was never a problem for the longtime professor; he claimed to have written "unlimited first chapters", and the beginning of The Lord of the Rings emerged whole with the story of Bilbo Baggin's birthday party.

Stanley Unwin shared the first bits of what would become The Fellowship of the Ring with his precocious son Rayner, who reported that he was "delighted." Other early readers showed similar excitement, including his friend C.S. Lewis, who had completed the classic Out of a Silent Planet mere months earlier. Competitiveness may have played some small part in pushing Tolkien onwards. As he continued his difficult task, he relied heavily on the advice of Lewis, his son Christopher, and at times young Rayner Unwin, whose early endorsement of The Hobbit had been crucial to that book's publication. Tolkien allowed them to read his new work chapter by chapter, like a magazine serial. On the surface, this seems a most disturbing way to approach a writing project, or any creative work, since repetition is the unfortunate consequence, and The Lord of the Rings is nothing if not extremely repetitive. Not to mention Tolkien also readily admitted he was "as susceptible as a dragon to flattery."

Nevertheless, by the end of 1939, Tolkien had progressed well into what would become The Fellowship of the Ring, finding himself at Balin's tomb in Moria.

In the real world, circumstances were not as accommodating. The Tolkien family was struggling financially, his wife Edith was sick, and war loomed on the horizon. As the project progressed, Tolkien sensed the scope of the enterprise he had unwittingly begun, yet could not help but recognize the core value in what he had written, saying, "the story has (I fondly imagine) some significance" - practically braggadocio from a depressed and humble man.

With the onset of World War II, food was scarce on the island of Britain. A German publisher offered to issue a translation of The Hobbit, but demanded that Tolkien write a letter insisting he was not Jewish. The author was upset and said so, but could not afford to pass on the opportunity. These and other distractions slowed his pace, but by 1942 he was ready to say The Lord of the Rings "is now approaching completion." It wasn't. Now his incipient worry was worry that the book would not appeal to the young audience he had cultivated with The Hobbit.

Tolkien was bothered by the state of England during the war, since his personal view endorsed total freedom. When his son Christopher was drafted into the Royal Air Force in 1943, he wrote, "my political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)," and the loss of liberty he felt during the war did not help the pace of his literary work. Depression hounded him, and he told his son, "we were born in a bleak age out of due time." England may as well have been cast in the shadows of Mordor. For over a year he did not look at the scraps of paper and multitude of random manuscripts that, at the time, constituted the novel.

The following year, however, he found himself able to return to The Lord of the Rings. He telegrammed his son Christopher to say, "How stupid everything is! and war multiplies the stupidity by 3 and its power by itself. I have seriously embarked on a effort to finish my book & have been getting up rather late: a lot of re-reading and research required. And it is continual sticky business getting into the swing again. I have gone back to Sam and Frodo, and am trying to work out their adventures. A few pages requires a lot of sweat: but at the moment they are just meeting Gollum."

Tolkien's concern for his son funnelled into and was absorbed by the work, and he sent his chapters for Christopher to read when he was not in the air. In a telegram he reflected that "Gollum continues to develop into a most intriguing character." Christopher objected strenuously to the name Samwise Gamgee, but Tolkien argued, "the object of the alliteration was precisely to bring the comicness." Tolkien never completely turned away from his own reading during the period, continuing to be engaged in both the academic and literary worlds. He read everything G.K. Chesterton produced - the man's books did double duty by troubling him and earning his admiration. Lewis' prolific, less rehearsed writing also inspired him, pushing him further into his own work.

In fall of 1946 Tolkien told his publisher - by then, very familiar words - that he intended to have a draft of the novel finished by the next year.

Rayner Unwin, returned from his own service in the war and newly employed by his father's company, read a semi-complete draft of the novel that July. He admired this early version, but readily admitted: "Quite honestly I don't know who is expected to read it." Discouraged, Tolkien managed to compose a rejoinder in his own defense, noting, "The world seems to be divided into impenetrable factions, Morlocks and Eloi, and others. But those that like this kind of thing at all, like it very much, and cannot get anything like enough of it, or at sufficient great length to appease hunger." In short, he knew he had a hit, but who else did?

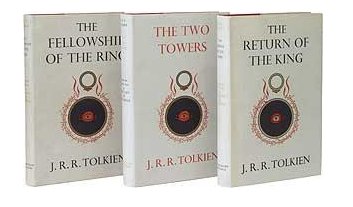

By the fall of 1948 Tolkien had managed to compile over 1200 pages of his sequel to The Hobbit. Sensing his publisher's lack of enthusiasm for the work (Stanley Unwin was no genius, financial or otherwise), Tolkien began taking inquiries from other imprints. He apologized to Unwin for "presenting such a problem" while boiling inside. In August of 1950, Unwin officially rejected The Lord of the Rings in its entirety, for there was no thought yet of splitting the book into discrete parts. Though no one had yet agreed to put the novel out, Tolkien was already in a panic about the maps that would have to be created for anyone to follow the plot.

When Rayner Unwin finally ascended to a position of prominence in his father's company, he begged Tolkien to resubmit the manuscript, which he had never seen in its entirety - it had just sat at their offices in a state of neglect. Together they agreed to split the book into three parts. Initially, they argued over what to call the second book - Tolkien did not care for The Two Towers, and the third volume was initially called The War of the King.

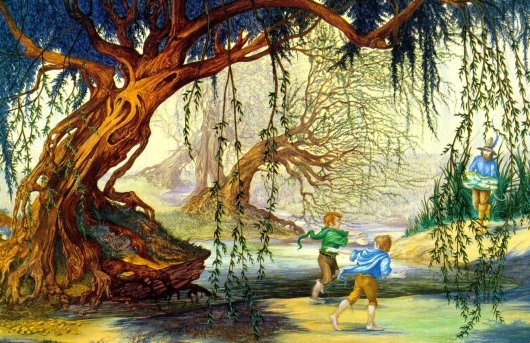

There was also a long discussion about what to do with the character of Tom Bombadil. Tolkien was in favor of leaving him in, writing, "He is a not an important person - to the narrative. I suppose he has some importance as a comment. I mean, I do not really write like that, he is just an invention, and he represents something that I feel important, though I would not be prepared to analyze the feeling precisely. I would not, however, have left him in if he did not have some kind of function.

There was also a long discussion about what to do with the character of Tom Bombadil. Tolkien was in favor of leaving him in, writing, "He is a not an important person - to the narrative. I suppose he has some importance as a comment. I mean, I do not really write like that, he is just an invention, and he represents something that I feel important, though I would not be prepared to analyze the feeling precisely. I would not, however, have left him in if he did not have some kind of function.

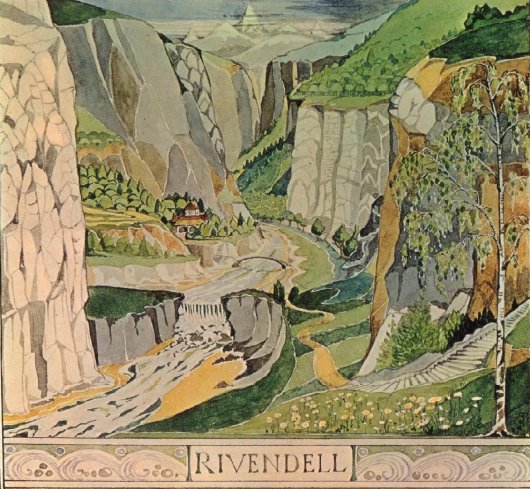

"I might put it this way - the story is cast in terms of a good side, and a bad side, beauty against ruthless ugliness, tyranny against kingship, moderated freedom with consent against compulsion that has long lost any object save mere power, and so on; but both sides in some degree, conservative or destructive, want a measure of control. But if you have, as it were, taken a vow of poverty, renounced control, and take your delight in things themselves without reference to yourself, watching, observing, and to some extent knowing, then the question of the rights and wrongs of power and control might become utterly meaningless to you, and the means of power quite valueless. It is a natural pacifist view, which always arises in the mind when there is war. But the view of Rivendell seems to be that it is an excellent thing to have represented, but that there are in fact things with which it cannot cope; and upon which its existence nonetheless depends. Ultimately, only the victory of the west will allow Bombadil to continue, or even to survive. Nothing would be left for him in the world of Sauron."

We imagine all authors of renown as confident successes. Tolkien spent the majority of his life as a somewhat impoverished academic and while he did feel support from his fans, with whom he would readily exchange lengthy correspondence on the thematic issues of his work, at no time was he ever anything but anxious about his future prospects as an author. It was only a vague sense that he would turn out to be right that allowed him to go on at all.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He is a writer living in New York. He tumbls here and twitters here. He last wrote in these pages about the marriage of Jean Stafford and Robert Lowell. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here.

"Lost Kids" - Blood Red Shoes (mp3)

"Cold" - Blood Red Shoes (mp3)

"Two Dead Minutes" - Blood Red Shoes (mp3)