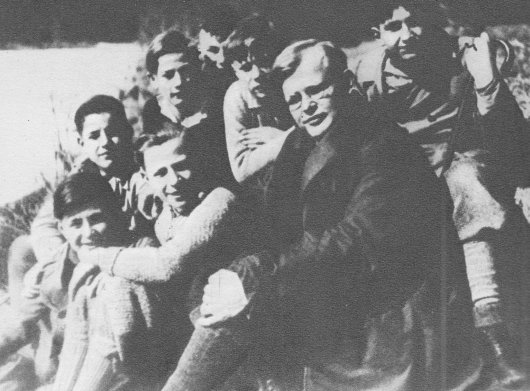

with his students in Germany

with his students in Germany

American Vacation

by JACQUE DE VRIES

Dietrich Bonhoeffer wanted to go to India. But he could not afford it, so he went to America instead.

When he first stepped foot in lower Manhattan, he was cowed by the size of the buildings. The year was 1930, and the Empire State Building was only just being built. I do not myself believe in the existence of an all-knowing being, but sometimes I feel I understand those who do better than those who don't.

Most troubling to Bonhoeffer about this country was its lack of freedom. Instead of being prohibited from drinking large beverages in restaurants, Bonhoeffer could not consume alcohol while in this country. He wrote to his Jewish friend that "Unfortunately I cannot even drink your health in a glass of wine, which is forbidden by law. This prohibition which nobody believes is a dreadful absurdity." Back home, the Nazi party consolidated its election gains.

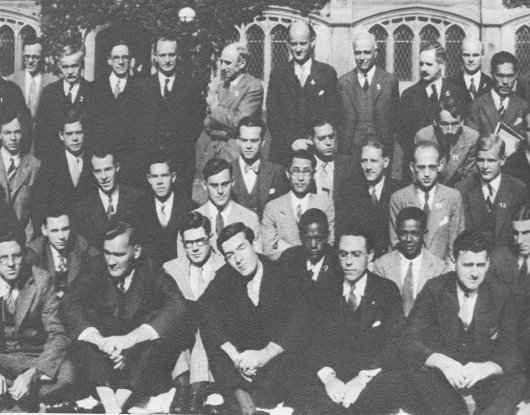

at the Union Theological Seminary

at the Union Theological Seminary

Many churches in New York desired his presence, but he expended the majority of his efforts in Harlem. He first surveyed the densely populated region from an airplane. He led groups of black women in Bible classes; his evenings were completely filled, and he never neglected his sight-seeing.

He did not want to stay in America, refusing a Harvard appointment at the age of 25, because of the legacy of slavery. He celebrated his birthday in the company of the New York Jews that housed him.

After he was arrested for trying to overthrow the Nazis, his first months in jail were full of hope that the plan would come to fruition. The letters he wrote and received in prison never despair. He was married shortly before his arrest, to this eighteen year old:

He was executed three weeks before Hitler's suicide effectively ended the war.

Bonhoeffer was surprised by the communal freedoms Americans took entirely for granted, what he called "social courage." In the academic life of his native Germany, it was verboten to each approach a professor outside of class if, for example, you saw him limping across campus. He was both envious and disdainful of his American peers in the Union Theological Seminary. He considered some of the students he met too jaded, others he found hopelessly innocent, and the qualities shifted even between individuals. He quantified it as a kind of naive pessimism.

The outreach programs of the churches he visited, and the social life that surrounded them seemed to replace the idea of a dedicated Christianity. The distinction, which Bonhoeffer eventually grasped, is completely misunderstood by many secular people. The foreign attitudes displayed in Bonhoeffer's appraisal of American literature were also confusing at first. The mixture of hard-won cynicism without a corresponding knowledge of the world baffled Bonhoeffer.

He had barely concerned himself with novels before now, and the ones he read, often autobiographical accounts by black writers, stoked a certain interest. He wrote his grandmother to say that the novel "always awakens in one the wish to get to know the man himself."

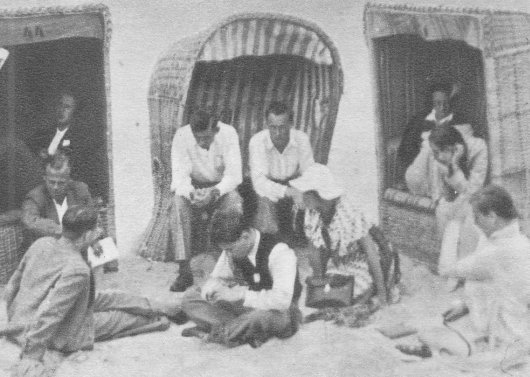

in prison

in prison

Before his execution, Bonhoeffer was moved to Buchenwald. On the truck the prisoners were enclosed in darkness. He shared his cigarettes with the other prisoners; he only liked to smoke every so often and had more than enough to satisfy that particular urge. He had been learning Russian in his last camp.

Even when I read de Tocqueville I feel first and foremost how easy it is to misunderstand America. With Bonhoeffer, there is nothing he says of this place that is not still true, and yet there are so many sins of omission it is difficult to decide where to start. It would take more than one lifetime, and he did not even have the one he was given.

in Kieckow, 1940

in Kieckow, 1940

The day of his death he did not want to hold a service demanded by the guards. He feared offending the other prisoners, many of whom were Catholics or not Christians at all. He was forced to do so anyway. His parents were the last to know he had been murdered.

His last act in America was to drive south with his friend Jean Lasserre. They travelled to the Mexican border in a decrepit Oldsmobile and entered the country by train. They made it all the way to Mexico City and then had to talk their way past the border on the return trip. If he had never left America. If he had never left Mexico. If he had never left Germany. These are just three of the infinite number of ways he might still be alive.

Jacque de Vries is a contributor to This Recording. This is his first appearance in these pages. He is a writer living in Chicago.

"I Love The Rights" - Silver Jews (mp3)

"The War In Apartment 1812" - Silver Jews (mp3)

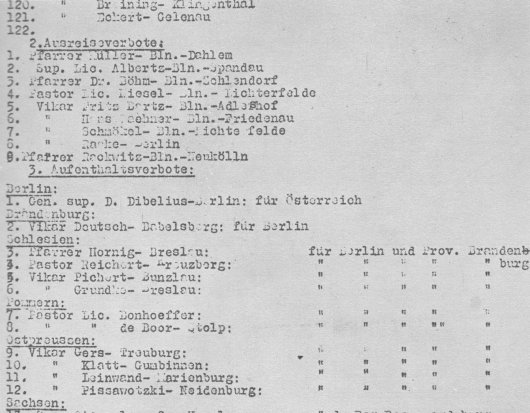

intercession list, july 1939

intercession list, july 1939