Temporary Equilibrium

by ELEANOR RAY

A bad poem is one that vanishes into meaning. - Paul Valéry

Arguing against Frank Stella’s famous assertion that “Painting is made with colored paint on a surface and what you see is what you see,” Philip Guston claimed that a painting is “not there physically at all.”

For Guston, who spoke energetically about his varied experiences with the paintings he admired, powerful works could not be seen quickly or definitively. “The art of the past is a hidden art,” he once said. Despite his acknowledged difficulties with talking about painting, Guston was unwilling to wave away the stubbornly elusive quality of the paintings, and the ordinary objects, that moved him. He understood that, as Wittgenstein put it, “The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity.”

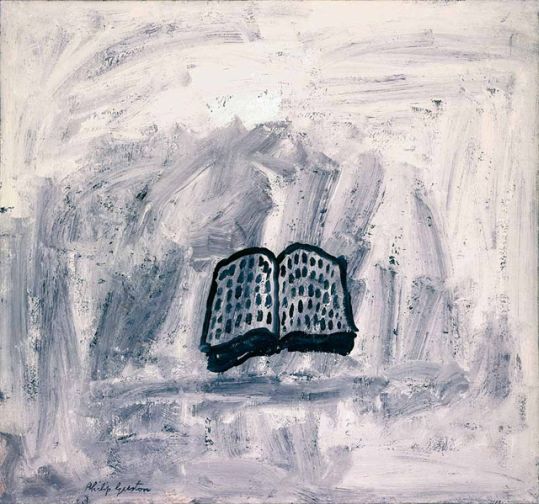

Philip Guston, Book, 1968, gouache on panel, 30 x 32 inches

Philip Guston, Book, 1968, gouache on panel, 30 x 32 inches

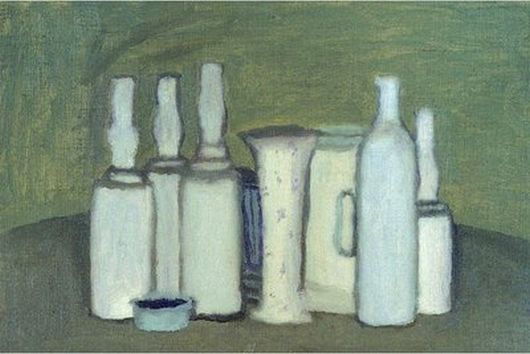

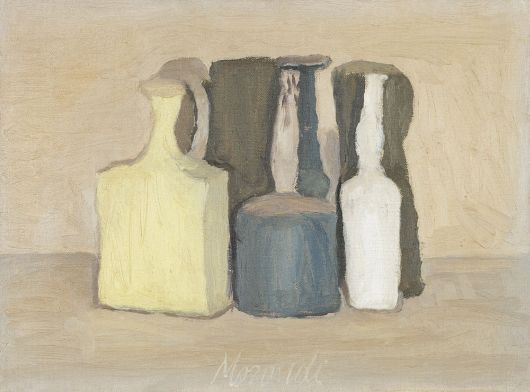

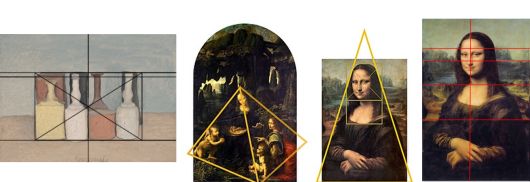

For Guston and Morandi, painting what was around them – books and shoes, bottles and boxes – provided a way to engage with certain aspects of painting that, while always in plain sight, refuse to be pinned down. Giorgio Morandi’s paintings reveal a heightened sensitivity to the basic problems and possibilities of painting. Looking at Morandi in my earliest painting years felt like learning to read for the first time. As a new painter, I must have had a sharpened awareness of the many possible mistakes threatening to undermine representations of a three-dimensional world – problems inevitably occurring in attempts to make certain objects appear further away than others, or to distinguish between masses and air. Morandi makes these difficulties his subject, turning them into exhilarating ambiguities.

Natura Morta (Still Life), 1954, Oil on canvas, 26 x 70 cm

Natura Morta (Still Life), 1954, Oil on canvas, 26 x 70 cm

In a long horizontal still life, the white stripe on a box’s front could be read as the top plane of a second box. The empty space to that box’s left begins to look like another, closer box, pressed against the surface of the painting, its top plane invisible at eye level. The objects to the right of the tallest box appear almost stuck to it, relying on it for support, and listing downwards with gravity as that support weakens. The grey back space appears to rest on top of the frieze of objects like a slab of stone.

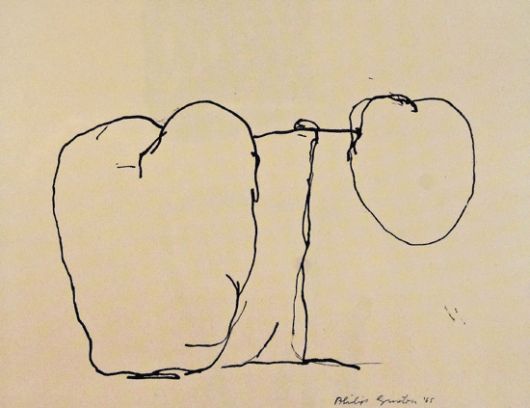

Objects clustered together form a heavy mass that seems to push a solitary, lighter object up, as if on a scale:

Philip Guston, The Scale, 1965

Philip Guston, The Scale, 1965

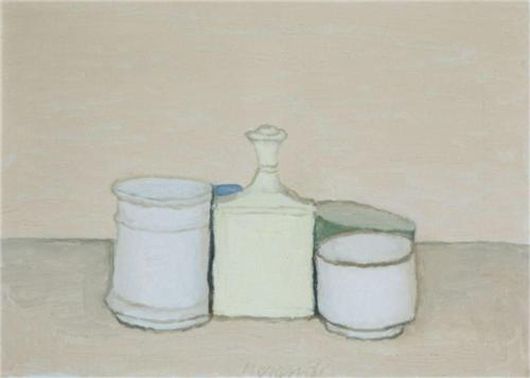

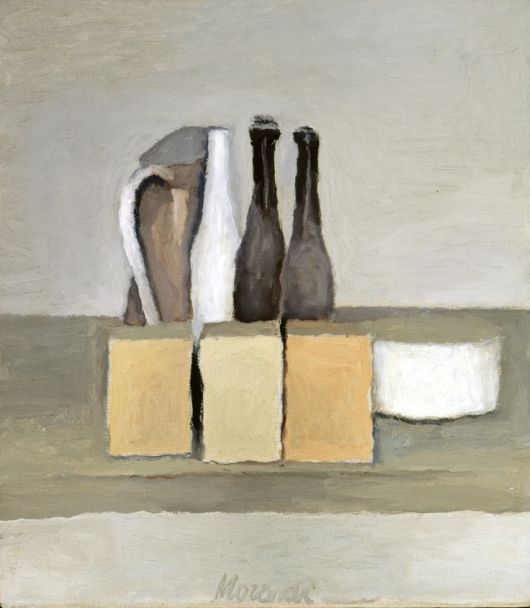

Morandi, Natura Morta (Still Life), 1956, oil on canvas

Morandi, Natura Morta (Still Life), 1956, oil on canvas

In their effort to balance an object lifted at their side, a mass of objects exerts pressure on the adjacent empty space, turning it into a palpable mass, an invisible object.

The necks of bottles swap places with the ones behind them and the spaces in between.

Darker objects recede into a hole, leaving the things in front of them to float uncertainly, the tallest among them holding up the framing space like a piece of a stage set.

A shadow falls onto a group of objects from off-stage.

Three rectangular orange shapes separated by decisive black lines stubbornly remain boxes, one set back from the others.

Morandi gives so much responsibility to a single line. Lines standing in for the space between two objects have an insistently tactile presence.

What is the meaning of a line? When does its meaning disappear?

Mondrian believed that representation and the “superficial trompe-l’oeil techniques of traditional art” veiled the abstract forces in painting. He sought to reveal what he called “the universal” by eliminating objects from his paintings, working only with relationships between colors and lines. Philip Guston, during a period of working abstractly, worried that making a recognizable image would lead his work to “vanish into meaning,” a favorite phrase he took from Paul Valéry.

After a period of working with only a few lines in ink, however, Guston then began to draw the things around him — books, shoes — and realized the importance to him of the “mask” of representation: “One of the difficulties with this essence thing is that it's not hidden. [It's] too evident. I don't think we want those forces to be so evident to us, that when they are somewhat masked they seem to last longer to me. In fact, I think that's where the enigma is, in the hidden."

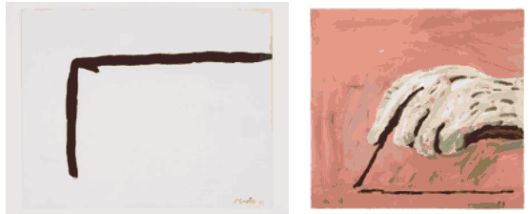

In conversations, Guston talked about the excitement of a mark becoming an image, a pleasure he could find in a single line: “I remember when I did this [Edge], that horizontal line, just like the edge of a box, that horizontal line seemed miles long.”

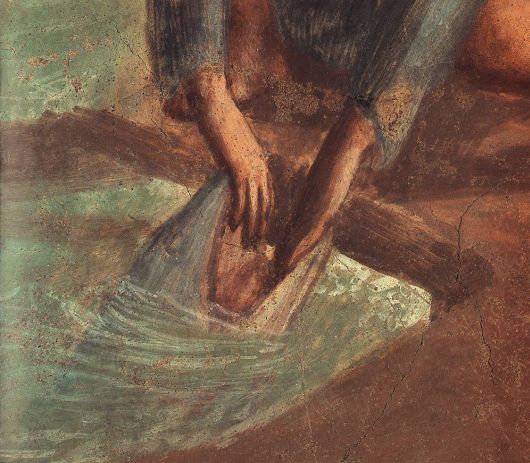

Philip Guston, Edge, 1967, and Paw, 1968In Paw, single lines mark the spaces between fingers on a hand, which, in turn, makes a line like the one in Edge. The quality of these lines recalls for me, or makes me more aware of, the human simplicity of hands painted by Giotto, Masaccio, or Manet.

Philip Guston, Edge, 1967, and Paw, 1968In Paw, single lines mark the spaces between fingers on a hand, which, in turn, makes a line like the one in Edge. The quality of these lines recalls for me, or makes me more aware of, the human simplicity of hands painted by Giotto, Masaccio, or Manet.

Masaccio, The Tribute Money (detail), c. 1424-28, Fresco, Brancacci Chapel, Florence. Detail of St. Peter’s hands retrieving tribute money from the mouth of a fish.

Masaccio, The Tribute Money (detail), c. 1424-28, Fresco, Brancacci Chapel, Florence. Detail of St. Peter’s hands retrieving tribute money from the mouth of a fish. Giotto, Resurrection (Noli me tangere) (detail), 1304-06, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

Giotto, Resurrection (Noli me tangere) (detail), 1304-06, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua

Édouard Manet, Olympia (detail), 1863

Édouard Manet, Olympia (detail), 1863

Like Wittgenstein’s language games, Morandi’s paintings work like a simplified version of our own language that helps us understand how we use words. He brings painting to the edge of representation, painting objects so simple that they are nearly reduced to shapes and lines, but never are. He locates the power of a line in the tension between its simplicity as a mark and its existence as something else — the space between two boxes or fingers. We can’t see a line or a shape in his still life as merely what it is because we can’t separate it from its participation in the painting’s representation. The language of painted notation disappears when you try to isolate it, as in the detail below. It remains visible only when hidden “under the shadows of natural objects.” (Cennino Cennini, 1437: “This is an occupation known as painting, which calls for imagination, and skill of hand, in order to discover things not seen, hiding themselves under the shadow of natural objects, and to fix them with the hand, presenting to plain sight what does not actually exist.”)

Morandi detail

Morandi detail

Going as far as Mondrian does in removing the veil of representation risks removing the veiled forces in the process. A diagram of the geometry in a painting is not more powerful than the painting itself. An explanation of the meaning of a word is not more useful than the word.

The tension between a line’s (or shape’s) essence and its mask is perhaps clearest to me at the outpost where Morandi’s work lives, though Stanley Lewis can convince me that this tension also becomes clear at an opposite outpost, that of representation in extreme, saturated detail.

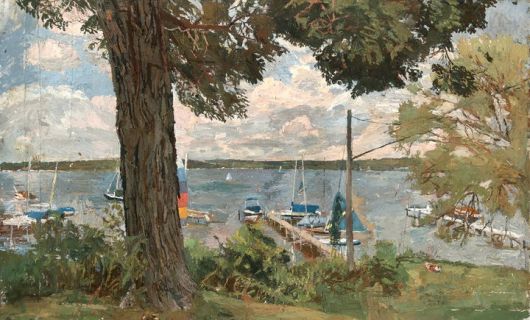

Stanley Lewis embeds a strikingly simple visual drama into his aggressively detailed and worked up surfaces. He organizes a complex landscape into large masses and volumes that influence each other like Morandi’s boxes. He relishes the sensation of one object passing behind another, disappearing from sight – a drama Guston called “delicious” in Piero della Francesca’s work, where “the spaces between the forms seem as important, as charged, as the volumes themselves.”

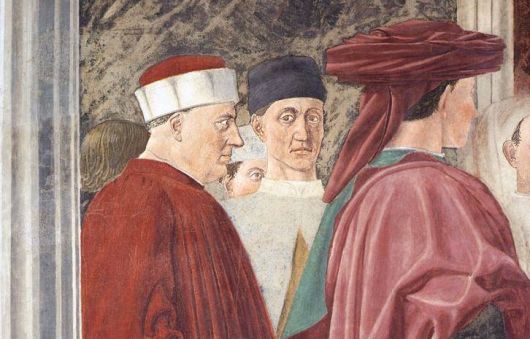

Piero della Francesca, Meeting between the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (detail), 1452-66, Fresco, San Francesco, Arezzo

Piero della Francesca, Meeting between the Queen of Sheba and King Solomon (detail), 1452-66, Fresco, San Francesco, Arezzo

Stanley Lewis, Lake Chautauqua July, 2010, Oil on canvas, 27 x 43 inches

Stanley Lewis, Lake Chautauqua July, 2010, Oil on canvas, 27 x 43 inches

In Lake Chautauqua July, a striped sail partially obscured by a tree becomes a metaphor for the vertically stacked landscape with its bands of sky, clouds, horizon, water, brush, and grass. The left side of the painting mimics the shape of the sail, its top edge formed by the curve of the tree. As soon as the sensation of this larger sail shape emerges, the space to the right of the tree begins to slip behind it like a tectonic plate, creating a current across the painting that the docks seem to follow.

This sensation of slippage implies a past and future for the image. But, despite its writhing details, the painting maintains a lucid stillness, and the motion of wind moving across water or passing through leaves remains suspended. John Goodrich referred to this quality in Stanley Lewis’ work as “a kind of quivering, temporary equilibrium.” Isn’t this also the equilibrium between abstraction and representation?

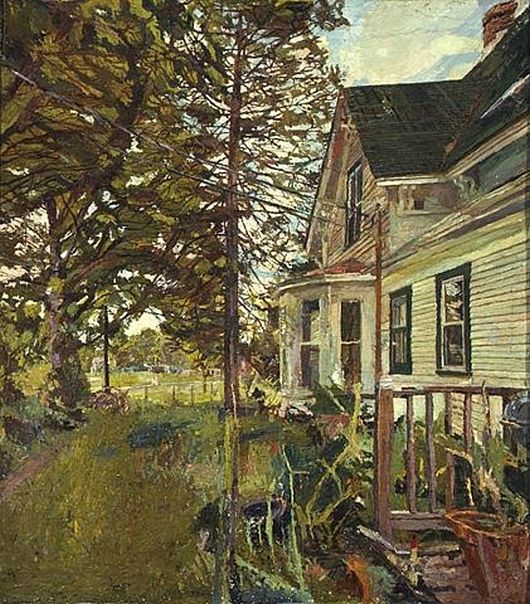

Stanley Lewis, West Side of House (with Detailed Shingles), 2001-2003, Oil on canvas, 32 x 37 inches In the lower right corner of West Side of House (with Detailed Shingles), a break in the surface — where the canvas has been cut and moved — abruptly interrupts the form of a terracotta pot. The pot appears to have broken open to reveal what it’s made of — juicy gobs of paint frozen in motion like dried lava. Stanley Lewis' paintings sometimes seem to be turned inside out, requiring you to see through their innards to an image. They remind me of Guston’s romantic dream of peeling open a painting by Rembrandt or El Greco to see what kind of teeming inner life of flames or fibers it contains.

Stanley Lewis, West Side of House (with Detailed Shingles), 2001-2003, Oil on canvas, 32 x 37 inches In the lower right corner of West Side of House (with Detailed Shingles), a break in the surface — where the canvas has been cut and moved — abruptly interrupts the form of a terracotta pot. The pot appears to have broken open to reveal what it’s made of — juicy gobs of paint frozen in motion like dried lava. Stanley Lewis' paintings sometimes seem to be turned inside out, requiring you to see through their innards to an image. They remind me of Guston’s romantic dream of peeling open a painting by Rembrandt or El Greco to see what kind of teeming inner life of flames or fibers it contains.

The inner materials Guston imagines for paintings provide an alternative to Frank Stella’s literalist declaration that “painting is made with colored paint on a surface.” The “quivering equilibrium” in Stanley Lewis’ work is one between matter and imaginative experience, between a teeming surface and a spatial world. We can’t fix what we see into paint or image alone, or force it into schematic generality; it remains hidden in its particularity.

Eleanor Ray is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is an artist and writer living in New York. You can find her website here. She last wrote in these pages about Elena Sisto.

Masaccio, Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St. Peter Enthroned (detail), 1424-28, fresco, Brancacci Chapel, Florence

Masaccio, Raising of the Son of Theophilus and St. Peter Enthroned (detail), 1424-28, fresco, Brancacci Chapel, Florence

Philip Guston, in a talk given at a conference at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, February 27, 1978:

In a recent article which contrasts the work of a color field painter with mine, the painter is quoted as saying, 'Painting is made with colored paint on a surface and what you see is what you see.' This popular and melancholy cliché is so remote from my own concern. In my experience a painting is not made with colors and paint at all. I don't know what a painting is…The painting is not on a surface, but on a plane which is imagined. It moves in a mind. It is not there physically at all. It is an illusion - a piece of magic, so what you see is not what you see.