The Body

by ANAÏS MATHERS

Ghosts do not happen alone. Ghosts are made

from rooms and glass and cherry trees. They lie down and become

horizons. You see by them.

You remember.

- C. Dylan Bassett

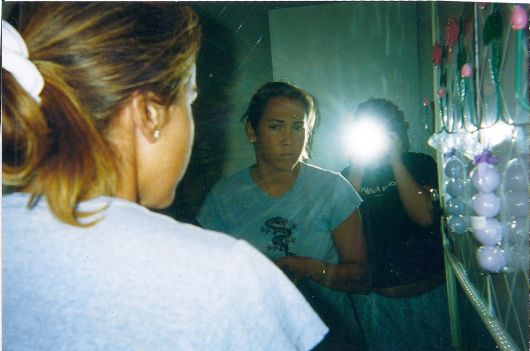

My mother was fifteen when my aunt was born, an only child through and through by the time she got the sibling she spent most of her early childhood asking for. My aunt was ten when she was the flower girl in my mother’s wedding and thirteen when I was born in late 1986. There’s a photo of her holding me in my nursery, her hair permed, her gangly limbs all-akimbo. Each of us grew up an only child, an only daughter. My mother had hoped I would be a boy for my grandfather’s sake but he was thrilled to have another little girl in the family, especially when I was born with the same birthmark on my waist that my great-grandfather had. It was all us girls and my aunt and I, we were thick as thieves from the start.

She was my aunt but we were also sisters. When my mom was running late, my aunt would pick me up from school and let me sit on her lap and steer while she drove. When my parents went out of town, she let me watch every movie they refused to let me watch and slept in my bed with me when those movies inevitably terrified me. When she moved to Chicago for a job, I spent weeks visiting her during summer vacation. We ate good food and awful food, stayed up late, and watched TV shows that would become favorites of mine: Seinfeld, Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The summer before I started high school she drank with me in her apartment so I would know how terrible I’d feel the next day. I still haven’t met anyone as cool as her.

My parents got divorced when I was fifteen and she was the only person I wanted to talk to about it. She left her job, moved back to Florida, and started her life over to be closer to me. She was still my sister then but she was also my friend and, most importantly, my mother. She got me a dog to help cheer me up, she bought my dresses for every homecoming dance and prom I went to, she made sure I went and that I didn’t let my heart harden that early. When I started having sex, she was the first person I told and she got me on the pill right away. She packed me up for college and sat on the phone with me as I cried about my first broken heart. She understood when I needed to take time away from school to just sort of be for a while. She made sure I grew up and she made sure I knew what loving someone meant.

I was almost twenty-two when she found out her kidneys were failing. She had always had health problems, having been diagnosed with juvenile diabetes when she was a baby, but this was different. I got tested along with the rest of my family to see if any of us were a match but none of us were; I was devastated. She was put on a transplant list and started dialysis. I moved back to the city I was raised in order to be close to her. When I could, I’d go to dialysis with her. We watched episodes of Hannah Montana and tried to figure out how it ever became a show. I put blankets on her when she was cold and folded them up when she got hot. We talked for hours while a machine made her kidneys function. She kept getting weaker but she kept traveling, doing all the things she loved, until she absolutely couldn’t. She still wanted to but her body was a lemon.

Two years after she was diagnosed, her body was done. She had a stroke the day before she was supposed to have surgery to put a stent in her heart. I wasn’t there when it happened, I was writing a paper for class; she didn’t wake up again. I went to the hospital the next day and saw the machines making her breathe; it was just a body, she wasn’t there. I kept repeating that, that she wasn’t there, until my grandfather pulled me out of the room before I upset my grandmother. I threw up in a trashcan in the hallway. I left that day and didn’t come back for two weeks, not until the day she was to be taken off life support.

It was a Saturday morning and family and friends cleared the room when I arrived. Her fingertips had started to turn black from lack of circulation and her skin felt cool and papery; she was already beginning to get stiff. The machines made her chest rise and fall but she was gone in the ways that counted. I tweezed her eyebrows, which had grown in over the past few weeks, knowing how meticulous she always was about them. When it came time to turn off the machines, I wept with my family and held her in my arms. The nurse looked at me.

“If she hears you sobbing like that, she won’t go,” she said. “I’ve seen it before.”

It took everything inside me, but I quieted myself somehow. I knew that it was just her body but I couldn’t let go of even that, of the hope that she would suddenly open her eyes. Her heart was at 40 BPM and as soon as I quieted down, it dropped to zero. It was over.

I watched the nurse remove the monitoring devices while my grandparents cried. I signed the required paperwork and made arrangements for her cremation. I watched them put a sheet over her body and stared at the familiar form, all at once strange to me. She looked so still and I couldn’t remember a time she had been that still in life. I wasn’t afraid as much as I was very aware of the surreal nature of such a moment. I took my grandparents home and didn’t cry again until I was alone with the dog my aunt had given me years before.

She and I rewatched Buffy while she was sick. We stopped after Season 4, making excuses as to why but both of us aware of what we were avoiding. We didn’t want to watch Buffy’s mom get sick and die in Season 5, we had seen it before and knew what was coming. Buffy’s mom, Joyce, recovers from her brain tumor only to pass away from a brain aneurysm a short while later. It was mundane yet earth shattering by Buffy standards. After all that time, it wasn’t a demon or vampire that took Buffy’s mom away but something she couldn’t fight. I remember how small I felt the first time I watched that but I had no idea what it actually felt like.

I began rewatching Buffy recently, finding myself as in love with it as I was as a kid and teenager but with the understanding and hindsight that comes with a decade more of living. I watched Joyce get sick and I watched her get better; I waited for what was coming. I watched “The Body” and waited for Buffy to find her mom’s body, to realize the finality of this loss, to see her change in a moment. I watched everyone else’s grief and felt my own as fresh as the day it happened. I didn’t expect it to feel that raw just like I never expect it to feel that raw whenever it hits me.

I remember my godfather passing away when I was ten. I remember crying because I was scared that someone would make me go near the body. I cried so hard during the service that my dad had to carry me out of the church and calm me down outside. I had nightmares for weeks about the body I hadn’t had to see, my mind creating a terrifying unknown. This was my first experience with death and yet not one at all; his death at a very elderly age seemed to make sense to me then but what was left behind to decompose, that’s what got me.

My aunt’s body never scared me though, maybe because I was older and better equipped to handle seeing it or because I knew her so well and loved her so much. It was heart-wrenching, it was surreal, it was odd, but it was never scary. I think that I just knew that a 37-year-old dying was so much worse, that the permanent loss of someone you love was terrifying. The most commonly mentioned highlight of “The Body” is ex-demon Anya’s honest questions about death and how it just makes no sense. It didn’t make sense and it never does. I will tell you almost three years later, and I suspect it will always be the case, that death will never make sense.

Some people become adults over time through a bunch of experiences that seem to slowly acclimate them to whatever it means to grow up. For some of us, it happens very suddenly and after you can pinpoint the exact moment you became an adult: Buffy grew up the instant her mom died, I grew up the instant my aunt died. My grief was mighty and I woke up every day for almost a year believing it would kill me and that I would never get through it only to find that I was doing just that. Beckett’s “I can’t go on, I’ll go on” looped endlessly in my head then. It got easier over time but it never dulled, it never stopped hurting. Even now, it’ll hit me suddenly and it feels as bad as the day it happened. I don’t know that time heals all wounds so much as that it fills your life so much that you seem to sometimes forget that the most terrible thing has happened to you.

You don’t forget though. I’ve made peace with what’s happened, stopped trying to make sense of such a senseless thing as death. It’s not death that haunts me but the memory, the living, the things that came before it all ended. It’s the knowledge and absence of what I’ve lost that hurts the most; this is my ghost. It never stops hurting, the big losses never do; it becomes a part of your bones. It rips you apart and leaves you to figure out what to do next. This ghost has informed how I choose to live, what I do, how I love. You will ache and you will hurt but you will be feeling, remembering not just the pain but how much love there was and how much there still is; death can never touch that.

Anaïs Mathers is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in South Florida. She last wrote in these pages about falling in love alone. She tumbls here and twitters here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"Only Tomorrow" - My Bloody Valentine (mp3)

"In Another Way" - My Bloody Valentine (mp3)