Thinking It's A Sign

by CATHALEEN QIAO CHEN

Ben Gibbard released a new song with Jenny Lewis a couple weeks ago. You’ve probably heard it already. It’s called “A Tattered Line of String,” and sounds pretty good. It’s a satisfactory Postal Service song with lots of synth beats, a handful of soppy-sad lyrics and a not-so-subtle reference to New York.

I didn’t think the song stuck with me until yesterday, when I had a dream about the pescetarian indie king himself. I was reading at Kafein, a local late-night coffeehouse that unfortunately turns into a hub for cringe-worthy performers every Monday night — the much feared and often forgotten Open Mic Night. Predictably, there’s the hoody-clad comedian who can only recite jokes about genitalia, the English-Theater double major slam poet, and the sensitive future engineer who has a knack for 1-5-6-4 chord progressions to accompany lyrics about heartbreak.

Tonight, the latter happens to be Gibbard. As he approaches the hemp rug that designates the performance area, I happen to look up from my extra foam soy cappuccino. Behind those horn-rimmed glasses, he averts his glance and grimaces. He is the sensitive future engineer, after all. He begins to strum his mahogany Taylor guitar with the Indian print woven strap. “And when I see you, I really see you upside down,” he sings in his honest voice, opening the acoustic ballad with a conjunction because why not. But my brain knows better. It picks you up and turns you around, turns you around, turns you around. He bobs his head ever so slightly as he plucks the simple rhythm. The stark twang of his melody reverberates in the hot, dingy café, pulling heartstrings and reigniting a roomful of teenage angst. He looks very sad and very cute in that plaid shirt.

If you feel discouraged that there’s a lack of color here, please don’t worry, lover. It’s really busting at the seams for absorbing everything, the spectrum from A to Z.

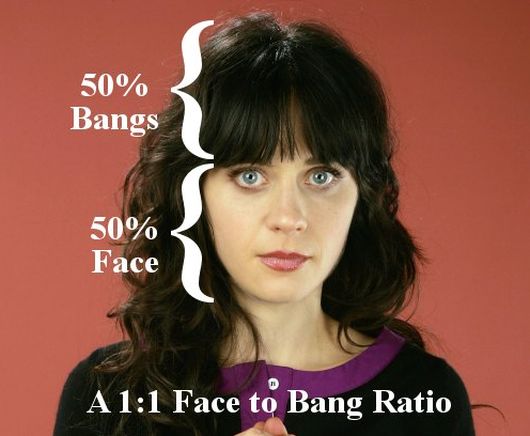

I brush back my overgrown bangs and hope to once again share eye contact with the gangly, longhaired crooner. But before the song could end, and before I could catch Ben Gibbard’s fancy with my unassuming whimsy and printed vintage dress, I woke up. I don’t have bangs. I’ve never had bangs in my life. I hate cappuccinos and I am not Zooey Deschanel, thank god. But Death Cab comprises well over half of my coming-of-age OST, and Ben Gibbard is unabashedly everything he was in my dream, heartthrob included. When I really got into Death Cab, my palette of emotions consisted of angry and sad. In my privileged, post-90s adolescence, this phase was dubbed angst.

I was in a small town high school, I hated my parents and I was recently dumped by a douchebag who always smirked at my music library because he listens to the Smiths. I really, really liked him. Anyhow, my life was characterized by the trifecta of teenage suffering and Ben Gibbard just happened to make himself available to me in the form of a pirated MP3 file. Naturally, I gravitated toward his earlier, darker stuff — songs for which he clearly took influence from the likes of Soundgarden and Smashing Pumpkins, the real angsty deal.

It would make sense to write Gibbard off as the chronically depressed hipster sellout from the Pacific Northwest, who dresses like a white guy and probably dances like one too. Or if you’re unfamiliar with Gibbard’s musical repertoire, you know him as the guy who married your favorite manic pixie dream girl. Ugh. On an outward level, Gibbard did sell out. After all, he did move to L.A.

Death Cab sold out stadium shows, and even wrote for the Twilight soundtrack. But it’s easy to forget that he’s been in the industry for 16 years, a period long enough to demand change. Before going platinum, before Madison Square Garden and before Zooey and that god awful collaboration with her on their last album, Codes and Keys, Gibbard and his indie setup were a bona fide basement rock band that fully embraced the local Seattle music scene.

Gibbard was an engineering student at a Washington university, performing on the side as the guitarist for a band called Pinwheel. He started Death Cab as a solo project and released his first demo on cassette in 1997 — You Can Play These Songs with Chords. It included tracks that would later be part of his first studio albums, like “Amputations” and “Champagne from a Paper Cup.” These were the original ballads that exhibited Gibbard’s signature sweet-and-sad disposition. The Postal Service came about before Death Cab’s launch into the mainstream with the perfectly pop-oriented 2003 album, Transatlanticism. As a side project, Gibbard collaborated with Jimmy Tamborello and Jenny Lewis by sending edited electronic tracks back and forth via mail — the U.S. Postal Service, hence the name. The trio released Give Up in February of 2003. I was hooked on Give Up long before I took a substantial interest in Death Cab. “Such Great Heights,” however ubiquitous in commercials and crappy TV shows, is pleasant, intelligent and emphatically catchy, all rolled into one four-minute track.

The mesmeric tune, sentimentalized by Iron and Wine with an acoustic cover, occasionally creeps into the most unforeseen moments of my life and before I even recognize it, I’ll already be humming the melody. Give Up is so charming that after the real postal service had threatened to sue over their trademark name, the band was able to win the government agency over to cooperate in some cross-promotional marketing. At one point, the USPS store actually sold the album, contributing to its platinum status.

With the exception of Give Up, I glossed over Death Cab’s earlier music, Transatlanticism included, until I heard “I Will Follow You into the Dark.” Unfortunately, I never stopped hearing it. Placed smack in the middle of Plans, the somewhat overrated acoustic ballad soon became Death Cab’s namesake song, and I regrettably was the culprit, along with Starbucks, elevators, and my high school classmates. Everyday for the entirety of 2006, I played the song on repeat.

When I began taking guitar lessons, I told my instructor Brian, a failed musician in the local Pittsburgh scene, that I absolutely needed to learn it. Little did he know what I truly wanted was to be serenaded by it. I’ve always believed Death Cab was the original emo band. And so just as I started getting into their earlier albums nearly a decade after the release of their debut, Something About Airplanes, my first boyfriend, the Smiths douchebag, broke my heart. No more serenade daydreams, and no more of that “love of mine” shit. The timing could not have been more apropos. I’ll react when faces find you with jealous fits that gag and bind you, Gibbard sings in “President of What." Cause nothing hurts like nothing at all when imagination takes full control.

I think Gibbard’s charm has always been that his songs projected his understanding of being broken, to the point that fans have become sadistic for his misery. Sure, he also has that shy, man-boy hipster image pinned down to perfection, but that might be more or less incidental. As Sharon Steel writes in a Stereogum deconstruction of Gibbard, “The singer-songwriter’s sadness certainly has a twisted currency in the indie rock community.” And that’s absolutely true. He writes songs about anxiety, numbing heartbreak, disillusionment, and any kind of mawkishness that fits under the category of deliciously sad. For the marginalized, the delicately heartsick or the existentially lost — archetypes anyone can take on — Gibbard’s music serves as a haven of comfort by normalizing and even romanticizing misery. Among the likes of Sylvia Plath, Tennessee Williams, Picasso in his Blue Period and Adele, Gibbard’s work revels in discontent.

That’s precisely why Death Cab fans criticized Codes and Keys as insincere. Pitchfork gave it a solid five, claiming “Death Cab weirdly sound like they are imitating themselves.” With lyrics like, “If there’s a burning in your heart, don’t be alarmed,” and “life is sweet in the belly of the beast,” it seems as if Gibbard had abandoned his Hancock of melancholy. It comes down to the fact that the album, on top of Gibbard’s 2012 solo record, Former Lives, resonate a sense of — god forbid — happiness. In “A Tattered Line of String,” we get a taste of that classic Gibbard despondence. “Everything never seems to hold,” he sings in the bridge.

Satisfactory indeed, but I couldn’t help but feel a tinge of guilt. His aching-for-heartache fans have objectified him to be the gospel for all that is angsty and disenchanted, when maybe he just had a phase. You know, the whole Soundgarden-and-Smashing Pumpkins-and-probably-Nirvana-too phase. Maybe he’s just a guy who had a quarter-life crisis in college and wrote songs about it, who gained a huge following for his relatably sad music, who later made the mistake of courting and marrying a vapid actress, who still writes pretty damn good music. Ben Gibbard is 36 years old. He is no longer a vegan. He ardently advocates for gay rights, and is living in Seattle again, where I presume he has a cat.

Gibbard denies rumors about The Postal Service’s reunion, but I have my fingers crossed. I’m building a fire to keep you warm long after I retire, he sings in the last track of his solo album. ’Cause this body is bound to expire/And the embers will glow, remind you what you already know, that the night is only a temporary absence of light, of light. It’s called “I’m Building A Fire,” and reminds me of the original Ben Gibbard serenade classic, “I Will Follow You Into The Dark.” It has just a haunting acoustic accompaniment and the lovely motif of death. And maybe, just maybe, I’m ready to be serenaded again.

Cathaleen Qiao Chen is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Washington D.C. You can find her twitter here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"I'm Building A Fire" - Ben Gibbard (mp3)

"Bigger Than Love" - Ben Gibbard (mp3)