A Genius of Dwelling

by ELLEN COPPERFIELD

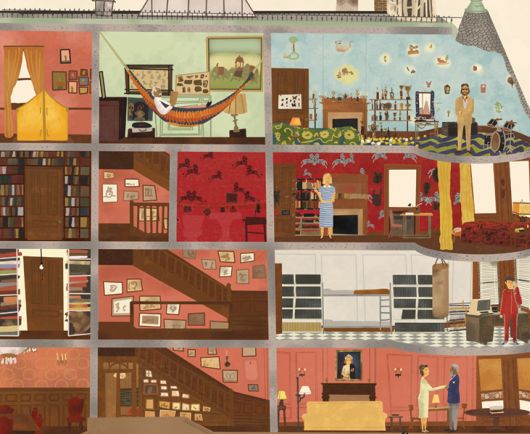

Walter Benjamin's father Emil was something of a dilettante. His major focus was the Berlin villa he purchased for his wife Pauline and their growing family. It was basically the house in The Royal Tenenbaums with nothing rotten or outdated; the culture it recalled had long since vanished from the earth.

At a very tender age Walter Benjamin was ensconced in a custom of indoor and outdoor living. If there was something to take lessons in - butterfly hunting or ice skating, for example — he joined with all the aplomb he could muster. Each room of his father's house held a different sort of emotion, and could be inhabited completely or discarded with the closing of a door.

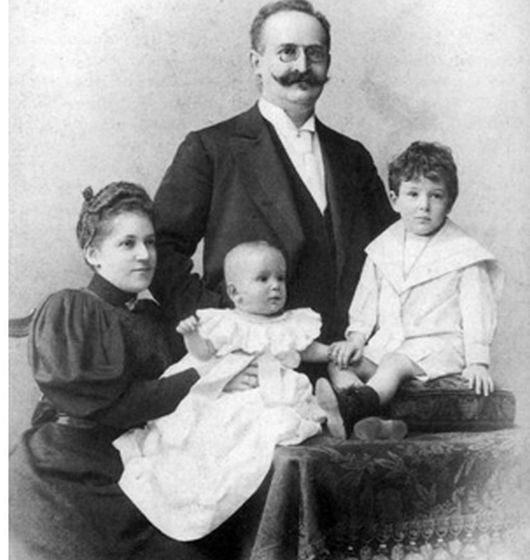

1902Emil's favorite place to be was on the telephone — this way a part of himself could be elsewhere, and a part with his family at all times. The self Emil Benjamin sent out, angry and forceful, was often different from the one they got back. His moustache was ranked either excellent or nonpareil depending on the humidity or time of day.

1902Emil's favorite place to be was on the telephone — this way a part of himself could be elsewhere, and a part with his family at all times. The self Emil Benjamin sent out, angry and forceful, was often different from the one they got back. His moustache was ranked either excellent or nonpareil depending on the humidity or time of day.

In a new biography from Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, Benjamin's younger days are given a reverent kind of attention as though they're depicting a young man either recovering from or developing a psychosis. In reality, Emil's disturbing utopia was all the more perplexing because it anticipated the complete destruction of the German residence, which perished during the war.

Walter's mother Pauline was thirteen years his father's junior. She called Walter "Mr. Clumsy" because he never lived up to her idea of decorum.

His brother and sister were both separated from Walter by age, Eiland reports, so that they each experienced life as an only child. When Walter was finally divested of his private tutors and send to class with other pupils, it may not surprise you to learn that he did not fit in whatsoever. He was sick so often that other arrangements had to be made; it was good to get those illnesses out in the open air.

In a country boarding school called Haubinda, Benjamin found a love of learning that separated him from all else — nothing was closer to him than that pedagogy. Upon his graduation from high school, his father gave him a trip as a gift. The family had already traveled around Europe at their leisure, this was Walter's first trip to Italy on his own, the first where he determined the direction and purpose: Como, Milan, Verona, Vicenza, Padua. Among the masters he never cowered.

This temporary elation passed, a miasma of longing mixed with a desire to survive persisted. At University Benjamin found himself again outside the times, and eventually he returned to the villa to live at home while he pursued his studies. He had one friend of any import, a painter/novelist named Philip, and he steered clear of everyone else.

University, Eiland and Jennings say, was Benjamin's first introduction to his Judaism. Really, it was only his first introduction to Zionism, because although the Benjamin family was entirely secular, the boy's upbringing was hardly divorced from some bare essentials of the European Jewish experience. He now fancied himself the quintessential Jew, and all of his friends were similarly disposed financially and ethnically.

Unsuccessful liasions with women would depress him, but their troubles never superseded his intellectual ones, and indeed possessed far simpler remedies.

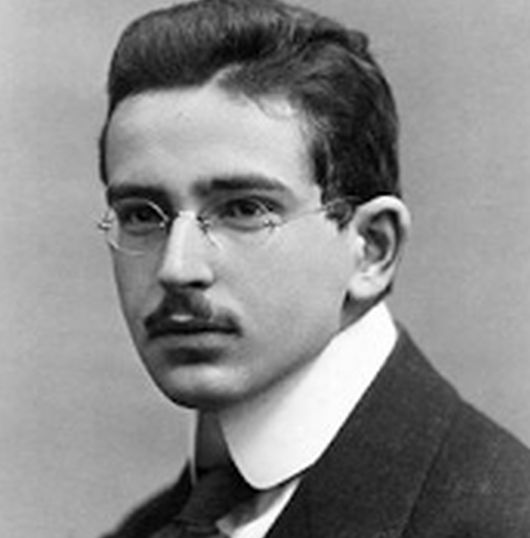

His friend Charlotte Wolff wrote of the man he became:

He had not the male bearing of his generation. And there were disturbing features about him which did not fit with the rest of his personality. The rosy apple-cheeks of a child, the black curly hair and fine brow were appealing, but there was sometimes a cynical glint in his eyes. His thick, sensuous lips, badly hidden by a moustache, were also an unexpected feature, not fitting with the rest. His posture and gestures were 'uptight' and lacked spontaneity, except when he spoke of things he was involved in or of people he loved.

He held, always, a part of himself back from those closest to him. Even his first amorous relationships with women never mention his body or theirs, as if he were describing two minds touching at the brainstem. All of Walter's friends felt this dissonance in their relationships with him: from the time he left home, he was far closer to ideas than people.

Ellen Copperfield is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in San Francisco. She last wrote in these pages about the life of Jules Verne. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"Rough Darlin'" - Fox and the Bird (mp3)

"When I Was Young" - Fox and the Bird (mp3)

The Best of Ellen Copperfield on This Recording

Dorothea Lange's Failed Marriage

Sex Life Of Marlon Brando

Lifetime of Threats and Insults

The Onset Of The Western Canon

Entitled To Madonna's Opinion

Barbra Streisand Grows Up In Flatbush

A Sneaking Suspicion of Literature

Anjelica Huston Falls Off The Horse

Prefer To Be Simone de Beauvoir

The Marriage of Mia Farrow and Frank Sinatra

Elongated Childhood of Jorge Luis Borges

Jokes At The Expense Of Tom Hanks

Which One Is The Gay?