Buried Face Down

by DURGA CHEW-BOSE

Seventeen

dir. Joel DeMott and Jeff Kreines

120 minutes

"You need a half-a-cup of white sugar and half-a-cup of brown,” instructs Mrs. Hartling, Southside High School’s Home Economics teacher. In Seventeen, the documentary by Joel DeMott and Jeff Kreines, Mrs. Hartling’s class is in the final lap of their senior year. They are loud and unimpressed, near delirious. Sitting on a counter, one boy casually beats batter with one hand while resting his head on the other. Another student, Lynn Massie, is taking a nap. When questioned about skipping class, one girl quips, “So?” Her parting shot, “Kiss my ass.”

The year is 1982. The town is Muncie, Indiana. And the kitchen classroom, like Mrs. Hartling’s shrill and grinding voice, her tunic apron and Estelle Getty glasses, is a time capsule dressed in blue checkerboard curtains, fluorescent lights, plywood cupboards, and beige stoves. Today, pie: “Never re-roll a pie crust! Ever!” Tomorrow, citizenship, and “how to be a good person, to be honest.”

Conceived and produced by Peter Davis for PBS, Middletown was a six-part television documentary inspired by the sociological studies of Robert and Helen Lynd, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture (1929) and Middletown in Transition: A Study in Cultural Conflicts (1937). Divided into categories — religion, work, politics, play, marriage, and education — the series is a close and critical meditation on everyday working class American life in the early 1980s.

Reminiscent of Robert Drew and D.A. Pennebaker, Middletown is a slow moving train, slackening its pace in Muncie. Happenings, whatever they may be, are coeval. The mayoral election no more important than the pizza parlor facing foreclosure or a couple’s second go at love.

But Seventeen, the sixth in the series, never made it to television. Scheduled to air nearly thirty years ago on April 28th, 1982, the film was deemed too controversial and ran into what Davis calls, “an institutional buzzsaw.” While it eventually went on to win the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, hailed as “without a doubt one of the greatest movies, perhaps the greatest, about teenage life ever made,” PBS’s decision to cut it from the series resembles an adult dismissing his or her adolescent years. A shame, because more so than revolt or hotheaded choices, a “me too” moment in high school is closest to windfall.

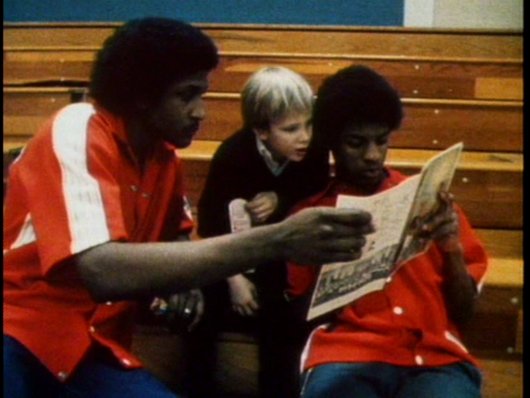

Teenagers being teenagers, the plenary account — smoking pot, “getting good and drunk,” merrily swearing, giving birth while the baby’s father is at “the Boy’s Club playing basketball,” being angry and scrappy and rude, partying and getting sad, reading “dirty books” out loud in the library, disrespecting teachers, crudely talking about sex — was simply too hot for TV. Like the girl in Mrs. Hartling’s class, whose duelling “So?” is nasty but also bankrupt and idle, Seventeen is a portrait of what it is to be young, pivoting from stitch to sweet spot, stitch to sweet spot.

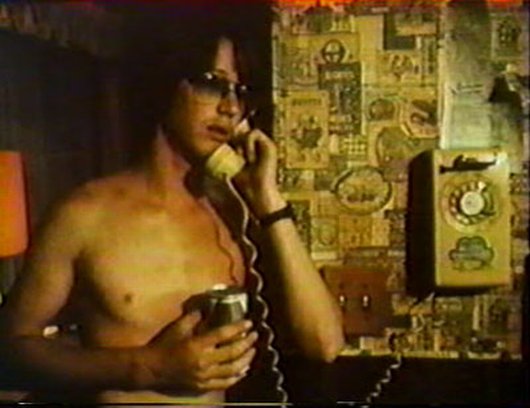

Perhaps most decisive was the subject of interracial dating: “White girls don’t mess with black guys but we swallow our pride for you guys because we care for you guys,” Tink and Massie inform their dates at the fair. When a cross is burned on Lynn parents’ lawn, she challenges the taboo and continues to see John. Harassing phone calls result; threats are made — parent to classmate, classmate to classmate. “My mom carries a gun and she ain't afraid to use it. Neither am I,” Lynn barks into the receiver.

In his 1985 review of the film, Vincent Canby likened Lynn to Belle Starr. One, a high school senior with Kristy McNichol hair, nervy swagger, and a slight squawk when she yells. The other, a 19th century Oklahoma outlaw. While the comparison is dreamy, it does appreciate the fugitive quality of adolescence, that roaming fidget and fixed urge to not give a damn. “Get me the hell outta here,” Lynn mumbles in monotone one day. She’s referring to Muncie. But without much of a plan, the here is more immediate: that day, that week, her house, a dip in her after school plans, her bad mood. Lynn's solution? “Gonna get bombed outta my head."

Although those rarely seen on screen bits are true (and do wonder what would happen if Albert Maysles, Larry Clark and Joey Jeremiah were to toss around a few ideas), Seventeen does enjoy the airier side of high school: the boys, the girls, the feelings, the prom, the epistolary mechanics of it all. In one scene, Lynn, who emerges as one of the Seventeen's main faces, sits in her car with her girlfriend and reads a note from a boy. She’s already read it, chances are more than once, and skips over words feverishly only to jump back and enjoy them for what feels like the first time. As if running her eyes up and down a BINGO card, anticipating a win, she holds the crumpled piece of paper breathlessly. Moments later, dulled by after school boredom, Lynn coolly admits to cheating on him multiple times. She chucks his note on the dashboard and smiles, “I went out on him all the time.” The girls laugh, roll down the windows, turn up the radio, and sing off-tune.

At the championship basketball game, angst fades and the gym’s yellow lights, the pompoms, the players, all burnish the crowd’s faces with what PBS originally had in mind. A row of high school seniors watching their last basketball game is a conceit often used in movies because it’s so easy to pretend the entire world exists in those minutes. Even Lynn lets loose a keenness she would never reveal to her teachers or parents.

Later that week Lynn invites everyone over for a party. Her parents, Jim and Shari, are present but not as chaperones. They drink with her friends, even making breakfast late into the night, drunkenly frying eggs and flipping pancakes. One boy chews on a piece of bacon, catching it before it falls out of his mouth. He can barely stand up. Nearby, an off-duty soldier shares his story about being “15 or 20 miles from the warzone,” as a crowd hangs on his every word. The Four Tops, “Reach Out I’ll Be There,” plays.

The house is chaotic but grows drowsy, and gets at why this, the documentary, is the best way to portray a teenager. Those moments on the weekend when the party starts to die down and boys get hungry and girls are told not to be shy, and unfailingly, someone is trying to revive the affair with music or booze, is specific to that time in life because later on, though the same nights recur over and over, “passing the time” is no longer a valid activity. Even the expression expires.

In the film’s most moving scene, a group gathers in a bedroom listening to the radio. Their friend, Church Mouse, has just died in a car accident and they’ve dedicated a song to him at the local station. “Crank it!” one boy shouts as Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind” begins. It plays in its entirety. The lyrics resonate sincerely — a perfect send-off. You realize early on that nobody will cry, and briefly, you half expect the friends to grow up before your very eyes. Never have you seen them so thoughtful at school. As the song fades, so do those sober minutes. Somebody mentions how Church Mouse was buried in his tennis shoes. He pauses and continues, “I wanna be buried face down so the world can kiss my ass.” And just like that, the kids are back. Gloriously so.

Durga Chew-Bose is the senior editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She last wrote in these pages about Rachel McAdams. She tumbls here and twitters here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"Old Love" - Witness (mp3)

"Twenty Years From Tomorrow" - Witness (mp3)

joel demott

joel demott