Garden of Snakes

by ETHAN PETERSON

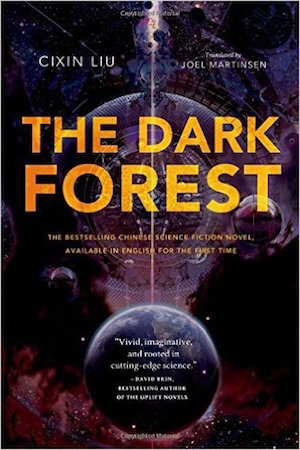

The Dark Forest

by Cixin Liu

Tor, 400 pp

Luo Ji wakes up from hibernation two hundred years in the future. Mankind lives underground. Above him, a projection of a clear blue sky arranges itself overheard. Wireless power propels cars and taxis through what could be called the atmosphere, but most people ride airbikes which elevate themselves to housing on the leaves of plants. After seventy percent of the world's population has died of starvation, things could not help but get better for the rest of us.

Luo Ji wakes up from hibernation two hundred years in the future. Mankind lives underground. Above him, a projection of a clear blue sky arranges itself overheard. Wireless power propels cars and taxis through what could be called the atmosphere, but most people ride airbikes which elevate themselves to housing on the leaves of plants. After seventy percent of the world's population has died of starvation, things could not help but get better for the rest of us.

For those born in democracies, science fiction has always taken on a cloistered, narrow futurism reflective of the political values we know and cherish. Advances in technology in a free society proceed at the pace of its most industrious citizens. Recently some private engineers launched and returned a spacecraft to the surface of the earth. It is unclear who even works at NASA or what they might be doing with their time.

In the China depicted by Cixin Liu in The Dark Forest, government is the only means of communication with the universe at large. An antenna built at Red Coast Base northwest of Beijing broadcasts a message to other galaxies. It receives a response: "Don't answer! Don't answer!! Don't answer!!!" Disgusted by the state of Chinese society during the cultural revolution, Ye Wenjie decides it would be prudent to summon an alien force that might eliminate humanity.

It is not a lot harder thinking of an American who wants to destroy America, so Wenjie finds the disenchanted son of a oil mangnate who possesses a dog-eared copy of Peter Singer's Animal Liberation. He contacts the aliens, who call themselves Trisolarans because their world contains three suns, and makes plans for Earth's destruction.

There are few European or American characters in Cixin Liu's imagining of first contact. Those that do penetrate the narrative are emotionally weak and disconnected from both society and faith. It is not really in Liu's vocabulary to imagine how a Christian or Jew might address these events; most everyone in The Dark Forest is a determined atheist, and the story of the Garden of Eden is mocked as an anti-science fable, albeit a strategically useful one.

When the aliens hear about this Bible tale, they immediately imagine humanity as the snake. It is Earthers who teach Trisolarans how to lie, since deception is not really a part of a culture who has no language beyond the transmission of thought. What the aliens do possess is overwhelming force, and the world plunges itself into cycles of despair and hope as the Trisolarans travel towards Earth at a hundredth of the speed of light.

The Dark Forest was preceded by The Three-Body Problem, which also served as a brief history of science - recounting advances in computing, space travel, astronomy and physics - from the perspective of a man outside the West. This was also a basic introduction for his native readers to the most basic of scientific concepts created by white men. In a virtual game devised to convert humans to the Trisolaran cause, avatars of Einstein, Copernicus, von Neumann, Newton and Galileo subvert Chinese values.

There is an underlying feeling of Chinese triumphalism in Liu's story of the future, but the translation by Joel Martinsen gives the term a sonorously positive quality. It is really more like patriotism elevated to a personal edict — the only way of coping against the onslaught of technology which consumes and eliminates the need for humanity.

As a scientist himself, Liu balances this fear of the future with broadsides in favor of technological advancement. He is an advocate for China to be the leader of every field, since he believes that technology is a kind of freedom that allows the eradication of the state. This subtle message in The Dark Forest is the most subversive portion of the text.

Liu's greatest skill is not his scientific expertise and imagination, although both are impressive. He shifts into the mind of a large cast of characters, never burdening us with excessive exposition. His psychological insight into how humanity regards itself is what has made his Three Body trilogy such a phenomenon here and abroad, as the spate of coming film adaptations attest.

Looking to Liu's finale to the series set to be published in English later this year, Death's End is likely to take as large a chronological and technological step as each of its predecessors. "I've always felt that extraterrestrial intelligence will be the greatest source of uncertainty for humanity's future," Liu proclaims in his afterword to The Three-Body Problem.

If that is true, than perhaps we need as many different national psychologies, and even types of people, as it is possible to create. One world culture is more vulnerable to disease, indoctrination and inflexible thinking than a diverse set of peoples and places. The worse thing we could be is united.

Ethan Peterson is a contributor to This Recording. This is his first appearance in these pages.

"Echo" - Eliza Hardy Jones (mp3)