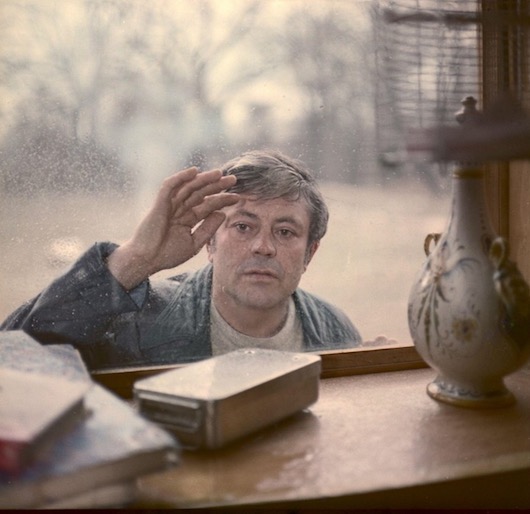

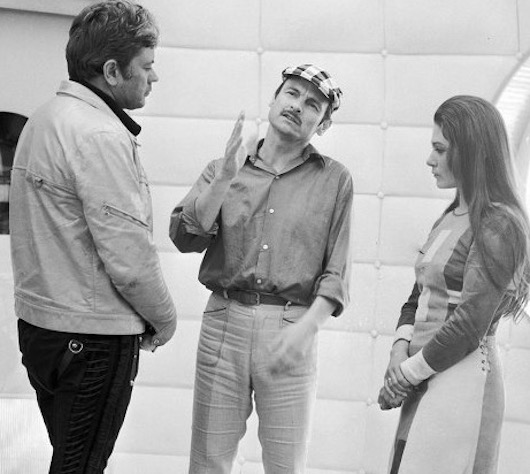

This is the second in a series on the letters on the Russian filmmaker and poet Andrei Tarkovsky. You can find the first part here.

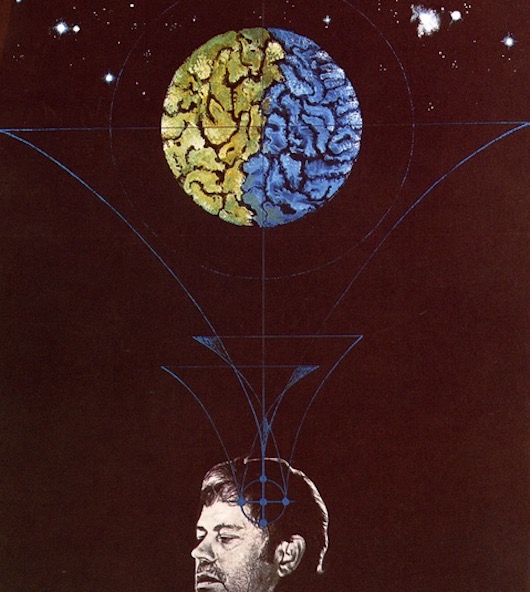

Full View of the Moon

The diaries of the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky are the notations of a man whose real enterprise was elsewhere. In the 1970s Tarkovsky's frustrations boiled over as he reached the peak of his cinematic powers. Tarkovsky's writing was purely a means to end — a way of framing his real language of filmmaking. As translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair, these notes on films like Solaris, The Mirror and unfinished and unrealized projects reveal Tarkovsky's struggle with the state, his family and himself.

January 21

I simply cannot work out what they meant, or rather, what was in their minds, when they gave me those corrections.

The corrections can’t possibly be made, they would ruin the whole film. And if I don’t make them? The whole thing is like a provocation, but I don’t see the point of it.

I’ve decided to make just those alterations that are consistent with my own plans and will not destroy the fabric of the film.

If that doesn’t satisfy them, then there’s nothing I can do about it.

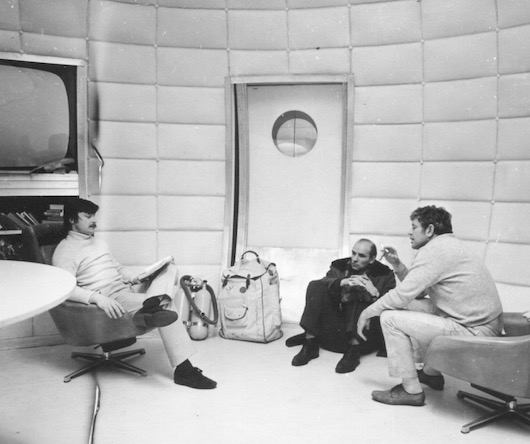

I went to see Yermash. Didn’t say a word about Solaris and the alterations. I asked him if I was an underground director and how long this persecution was going to go on, and would I be able to go on making two films a year (ugh! I couldn’t even bring myself to write the truth: two films in ten years). Yermash replied that I was entirely Soviet and that it’s a disgrace that I do so little work. I said in that case, please support me and guarantee me work. Otherwise I shall have to start taking defensive action myself.

In fact they are going to have to allow Solaris if they don’t want a serious row. Because I’m not prepared to sit there quietly without work, not saying a word, looking on while they violate the constitu- tion.

February 15

A STORY

Someone is given the opportunity to become happy. He is afraid to use it, because he thinks happiness is impossible, and that only a madman can be happy. Circumstances somehow convince our hero to use the opportunity and—by some sort of miraculous means— to become happy.

And he goes mad. He is drawn into the world of the insane, who may not merely be mad; they are also able to link up with the world by means of threads which are inaccessible to normal people.

For many years I have been tormented by the certainty that the most extraordinary discoveries await us in the sphere of Time. We know less about time than about anything else.

December 23

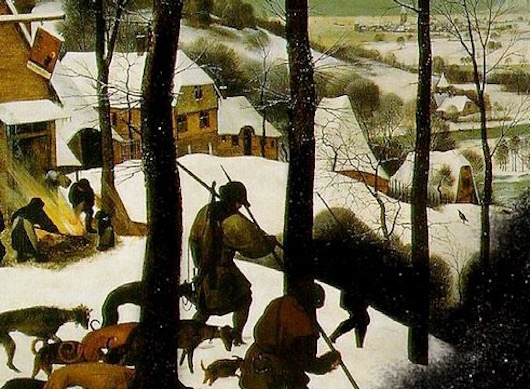

Three months since I touched this notebook, and so much has happened. I have been in Italy and Brussels and Luxemburg and Bruges. And then in Paris where I cut Solaris by 12 minutes for the French version. In Belgium I saw Erasmus’ house, and the paintings of Memling, Van Eyck and Brueghel.

Paris is beautiful. You feel free there: nobody needs you, and you don’t need anybody.

I didn’t like Italy this time. Maybe it was because of the company, maybe because this time it struck me as twee, picture postcardish. (We went to Sorrento and Naples.) Rome was overwhelming. It’s an amazing city. If in other cities you can see year-rings like on a tree, in Rome what you see are the rings of decades, or even perhaps of epochs.

January 24

There was a time when I thought that film, unlike other art forms, (being the most democratic of them all) had a total effect, identical for every audience. That it was first and foremost a series of recorded images; that the images are photographic and unequivocal. That being so, because it appears unambiguous, it is going to be perceived in one and the same way by everyone who sees it. (Up to a certain point, obviously.)

But I was wrong. One has to work out a principle which allows for film to affect people individually. The ‘total’ image must become something private. (Comparable with the images of literature, painting, poetry, music.)

The basic principles it were, the mainspring – is, I think, that as little as possible has actually to be shown, and from that little the audience has to build up an idea of the rest, of the whole. In my view that has to be the basis for constructing the cinematographic image. And if one looks at it from the point of view of symbols, then the symbol in cinema is a symbol of nature, of reality. Of course it isn’t a question of details, but of what is hidden.

March 23

Something has been happening to me recently. Today that feeling is particularly strong and significant, I’m preoccupied by it. I have started to feel that the time has come when I am ready to make the most important work of my life.

The guarantee that this is so is, first, my own certainty (which of course can be deceptive and turn out — dialectically — to be a run- of-the-mill disaster); and, second, the material which I am going to use – which is simple, but at the same time extraordinarily profound; familiar and banal — to the point where one will not be distracted, not drawn away from what matters.

I would even call it ideal material, because I feel and know it so well, I’m so aware of it. The only question is, shall I be able to do it? Shall I be able to imbue the perfectly constructed body with a soul?

December 8

Returned from Yurevetz this morning. We went as far as Kinechma by train, and after that by taxi.

It was cold, everything was covered in snow. Yurevetz made no impression on me. It was as if I was seeing it for the first time. I recognized the school I used to go to, and the house where we lived during the War. The sandy hill behind the school has been levelled and there’s a skating pond where it used to be. St. Simon’s Church has a hedge all around it, and in the main square they’ve built two hideous buildings — the consumer services centre and the town hall. Part of the boulevard beside the river has been demolished, in fact all of it has, and where the street used to be they have built a dam, to protect the town from the spreading waters of the Volga. If you ever go there...

June 27

Last night I dreamt that I had died. But I could see, or rather feel, what was going on around me. I could feel that Lara was beside me, and one of my friends.

I felt I had no strength or will, I was only capable of witnessing my own death, my own corpse.

Above all, I could feel in my dream something long forgotten, something that had not happened to me for a long time — the feeling that it was not a dream but real.

It is such a powerful sensation that a wave of sadness fills your soul, of pity for yourself, and a strange, as it were aesthetic way of seeing your own life. When you feel compassion for yourself in that way, it is as if your pain were someone else’s, and you are looking at it from outside, weighing it up, and you are beyond the bounds of what used to be your life. It was as if my past life was a child’s life, without experience, unprotected. Time ceases to exist, and fear. An awareness of immortality.

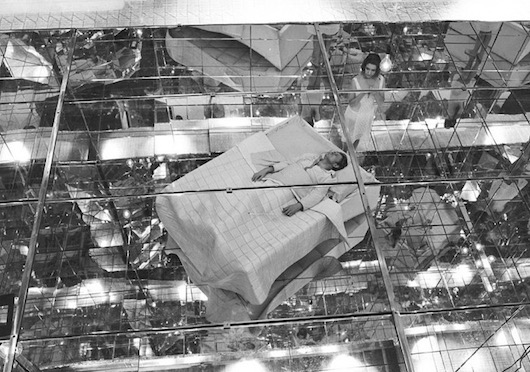

I could see (from above, from somewhere on the ceiling) the spot where they were setting up supports for the coffin, and everyone was very busy because I had died.

And then I came back to life, and no one was surprised.

They all went off to the public baths, and I wasn’t allowed in because I didn’t have a ticket. I pretended I was the bath attendant, but I couldn’t produce any proof of identity.

But all that was just a dream, and I knew it was a dream.

It’s the second time I have had a dream about death. And each time I have felt an extraordinary sense of freedom, of not needing any kind of protection. What can it mean?

The interview with Bergman where he says I am the best contemporary director is in Playboy.

July 4

Give up private property... In order to give up something you have to refuse something that is actually there. And I have no experience of private property. How can I give up something I have never known in my life? That is at the root of one of the basic ideological errors.

Reading Max Frisch’s Stiller. He is clever. Too clever for a good writer. He is precise, economical; charming. Like a tiny Japanese garden.

He is very nice, and very like his characters. That is not a plus, either. I know him. He gave Larissa and me supper near Locarno. He was with his mistress, whom everybody in Switzerland condemned just for being his mistress.

It was a delicious supper; a delightful restaurant with tables set under the oak trees. And all the people who condemned her and had been invited, were making pleasant, easy conversation with her and smiling. Is that being well brought up? Hypocrisy? Humbug? Snobbishness? Anyhow, I liked him. A real Puss-in-Boots.

How lovely it is here in Myasnoye. I have a wonderful room.

September 13

We all either underestimate each other, or else exaggerate each other’s virtues. Very few people are capable of assessing others as they deserve. It is a particular gift. In fact I would even say that only the great are capable of it.

At 11.30 at night we went out into the meadow to watch the moon through the mist. It was unbelievably beautiful!

An episode: Several people gazing at the moon, in the mist, enjoying it. They stand in silence; move around. Delighted faces; all have the same sort of expression; the look in their eyes almost one of pain.

NB: Must read through my will.

I must learn to use a cine-camera, and do some filming here. It is possible to attain immortality.

Dostoievsky:

1. Text, read by a character.

2. Different scene. Pause.

3. Abstraction — from the lives of characters imitating the characters of Dostoievsky.

4. Piercing music, something very simple (Bach or earlier).

Dearest Larochka! How grateful I am to you for this house. For understanding what matters to us.

We need peace; but not only peace.

A flock of rooks came flying over, and was attacked by a hawk, which brought one of them down. We rescued him, and now he’s living with us. He tries to peck you; and eats very little. What is love? I don’t know. Not that I don’t know love, but I don’t know how to define it.