The Most of Myself

The following conversation between Robert Bresson and Jean-Luc Godard took place at the end of 1966. Bresson was about to embark on the production for his film Mouchette, just a few months after completing his previous film.

JEAN-LUC GODARD: I have the impression that this film, Au hasard Balthazar, speaks to something very old in you, something you've been thinking about for at least fifteen years, and that all the films you've made during that time have anticipated this one. That's why it seems as if all of your other films can be found in Balthazar. In fact, it's your other films that prefigured this one, as if they were fragments of it.

ROBERT BRESSON: I have thought about it for a long time, but without working on it; that is to say, I worked on it in spurts. I would tire quickly. It was very difficult from the point of view of composition. Because I didn't want to make a film out of sketches, and I wanted this donkey to cross paths with specific groups of humanity that represent its vices. So it was necessary for the groups of people to become involved with one another.

It was also necessary, given that the life of a donkey is a very stable, serene life, to find a movement, a dramatic arc. I had to find a character whose life could parallel the donkey's life, someone who would create this movement, who would give the film the dramatic arc it required. That's when I thought of a girl, a lost little girl. Or rather, the girl who loses herself, and whom I named Marie.

J-LG: When you were creating this donkey character, did you think about the characters from your other films? Because in watching Balthazar today, we get the impression that he has been in all of your films, that he passed through them all. I mean that with him, we also encounter Pickpocket, and Chantal from Diary of a Country Priest, and that makes this seem the most complete of your films. It's the total film "in itself", and with respect to you. Do you agree?

RB: I did not have this feeling while making the film, even though I'd been thinking about it for ten or twelve years. Not continuously. There were off-moments of absolute not-thinking, which might last two or three years. I took up the film, left it, took it up again. . . . At times, I found it too difficult, and I thought I would never make it. So it's true that I thought about it for a long time. And it's possible that what it was, or what it was going to be, can be found in my other films. It seems to me that it's also the freest film I've made, the one to which I've given the most of myself.

You know, it's difficult, usually, to put something of yourself in a film that has to be approved by a producer. But I believe it's good, that it's indispensable even, for films to be made from our experience. I mean, that they not be "set pieces" or merely the execution of a plan (and by plan I also mean project). So a film must not be the pure and simple execution of a plan, even a plan that is personal to you, and even less a plan that is someone else's.

J-LG: Do you feel that your other films were more "set-pieces" than this one? I don't get that impression.

RB: That's not what I meant to say. But for example, when I work with Diary of a Country Priest, which is a book by Bernanos, or with Devigny's story that was the inspiration for A Man Escaped, I'm choosing to work with a subject that hasn't come from me, one that's been approved by a producer; and given that, I try as much as possible to put myself into it. Now, I don't think it's a terrible thing to start from an idea that comes from elsewhere, but in the case of Balthazar, it's possible that the fact that it came from a personal idea, one I had worked on enormously in my mind, even before I started to work on it on paper, it's possible that this is responsible for the impression you have — which gives me a lot of pleasure — that I really put myself into this film, even more than into my other films.

J-LG: I ran into you once, while you were filming, and you said to me, "It's very difficult, I'm improvising a bit." What did you mean by that?

RB: For me, improvisation is fundamental to the creation of cinema. But it's also true that, for a fairly complex work, you need a foundation, a solid foundation. In order to modify something, the point of departure of the thing needs to be very clean and strong. Because without not only a very clean vision of things, but also something written down on paper, you risk getting lost in it. You risk getting lost in a labyrinth of extremely complex givens. You sense, on the contrary, so much more liberty with respect to the structure of a film you've forced yourself to outline, to build that strong foundation.

J-LG: To give you an example: I get the sense that the scene with the sheep at the end is one of the elements that's more improvised than others. Maybe in the beginning you imagined only three or four sheep?

RB: You're right about the improvisation, but not about the number. In fact, I had imagined three or four thousand sheep. I just didn't have them. That's where improvisation came in. I had to pen them together so the group didn't seem too thin (it's like trying to create the impression of a forest with three or four trees), but it always seems to me that what comes quickly, without reflection, is the best work one does. I've done my best work when I've found myself solving problems with the camera that I couldn't fix on paper, that I'd left blank. The vision of things that you discover in an instant behind the camera, that you couldn't have gotten to with words and ideas on paper; you discover or rediscover it in the most cinematographic way that exists, meaning the most creative, the most powerful.

J-LG: I think we might say that for the first time you're describing, or narrating, several things at once (I don't mean that in a pejorative way, not at all) whereas up to now (in Pickpocket, for example), everything happened as if you were following a thread, as if you were exploring a single thread. Here, there are several threads at once.

RB: I agree that the storylines of my other films are quite simple, quite obvious, whereas that of Balthazar is made up of many lines that intersect. And it was the contact between them, even when it was accidental, that sparked my most creative work, at the same time forcing me, perhaps unconsciously, to put more of myself into this film. I believe very strongly in working intuitively. But only after a long period of reflection. Specifically, reflection regarding composition. It seems to me that composition is very important, that perhaps composition is even the point of origin of a film.

That said, the composition can be spontaneous, can spring from improvisation. In any case: it's the composition that makes the film. Because we're taking elements that already exist: what matters is the connections between things, their proximity, and in the end, their composition. Sometimes it's precisely in the relations — which can be very intuitive — that we establish between things that we are able to find ourselves. And I'm thinking of another fact: It's also by way of intuition that we discover another person. In any case, more so by intuition than by reflection.

In Balthazar, the abundance of variables and the difficulties caused by them forced me to expend an extraordinary amount of effort: first, during the writing on paper, and then during the shooting, everything was extremely difficult to accomplish. So I didn't realize that three-quarters of my shots were exteriors! Now, if you think about the rainfall we had last year, you understand what that meant in terms of additional difficulties. Even more so since I wanted all of my shots to take place in sunlight. And I did, in the end, shoot only beneath sunlight.

J-LG: Why were you so committed to sunlight?

RB: It's very simple, really. I have seen too many films where it's gray or dark outside — which can create a very beautiful effect, of course — but then the next shot suddenly shifts into a sunny room. I've always found that unacceptable. But it happens so often when we move between interiors and exteriors because there's always additional lighting inside, artificial light, and when we go outside this disappears. Which causes a completely false disconnect. Now, you are aware — and surely you're like me in this respect — that I'm obsessed with the real. Down to the smallest detail. Fake lighting is as treacherous as fake dialogue, fake gestures. Which is where my concern for an equilibrium of light comes from, so that when we enter a house there will be less sunlight than there was outside. Am I being clear?

J-LG: Yes, yes. Very clear.

RB: There's another reason that may be more correct, more profound. You know that I lean toward the side — not intentionally, mind you — of simplification. And let me clarify right away: I believe that simplification is something one must never seek. If you've worked hard enough, simplification should arrive of its own accord. But you must not look for simplification, or simplicity, too soon, for that's what leads to bad painting, bad literature, bad poetry. . . . So I lean toward simplification — and I barely realize it — but this simplification requires, from the point of view of the photographic shot, a certain force, a certain vigor. If I simplify my plot and at the same time my image fails (because the contours aren't well enough defined, the contrast isn't strong enough), I risk falling into mere sequence. I, like you, believe that the camera is a dangerous thing; meaning it's too easy, too convenient, we have to almost forgive ourselves for it: but we have to know how to use it.

J-LG: Yes, you have to, if I can say it like this, desecrate the technology of the camera, push it to its . . . But for me, I do that differently as I'm more, let's say, impulsive. In any case, you can't take it for what it is. Like the fact that you wanted sunshine so that the shot wouldn't collapse. You forced it that way, to keep its dignity, its rigor . . . which three-quarters of the rest don't do.

RB: That's to say that you have to know exactly what you want in terms of aesthetics, and do what you need to do to realize it. The image you have in your mind, you have to see it in advance, literally see it on the screen (understanding that there will be a distinction, even a total difference between what you see and what you end up with), and this image. You have to make it exactly the way you desire it, the way you see it when you close your eyes.

J-LG: You've been called the cineaste of ellipses. I imagine that for people who watch your films with this idea in mind, you've outdone yourself with Balthazar. I'll give you an example: In the scene with the two car accidents (if we can say two, since we see only one of them), do you feel as if you're creating an ellipsis by showing just the first one? I don't think you thought of this as withholding a shot, but as placing one shot after another shot. Is this true?

RB: Concerning the two skidding cars, I think because we've already seen the first, it's pointless to show the second. I prefer to let people imagine it. If I had made people imagine the first one, then there would have been something lacking. And I like seeing it: I find it pretty, a car spinning around on the road. But after that, I'd rather make the next image out of sound. Any chance I can replace an image with a sound, I do. And I do it more and more.

J-LG: And if you were able to replace all of the images with sounds? I mean . . . I'm thinking about a kind of inversion of the functions of image and sound. We could have images, sure, but it would be the sound that would be the important element.

RB: As far as that goes, it's true that the ear is much more creative than the eye. The eye is lazy. The ear, on the contrary, is inventive: it's much more attentive, whereas the eye is content to receive, other than in exceptional cases when it, too, invents, but through fantasy. The ear is, in some sense, far more evocative and profound. The whistle of a train, for example, can call to mind the image of an entire station: sometimes of a precise station you know, sometimes of the atmosphere of a station, or of tracks with a stopped train. The possible evocations are innumerable. What's good about this, this function of sound, is that it leaves the viewer free. And that's what we must strive toward: leaving viewers as free as possible. And at the same time, you have to make them learn to love this freedom. You have to make them love the way you render things. That is, show them things in the order and in the way in which you want them seen and felt; make others see those things, by presenting them in the way you see them and feel them yourself; and do all of this while leaving them great liberty, while making them free. Now, sound evokes this freedom in greater measure than does imagery.

J-LG: Why focus on vice? For me, humanity is not only about vice.

RB: The film takes two ideas, two schemes, if you like, as its points of departure. First scheme: The donkey takes the same steps in his life that man does. That is to say: childhood (caresses); maturity (work, talent, the genius/brilliance of mid-life); and then the mystical period that comes before death. Second scheme, which overlaps with this one and becomes a part of it: the trajectory of this donkey that happens upon different groups representing the vices of humanity, from which they suffer and die. So those are the two schemes, and that's why I mentioned the vices of humanity. Because the donkey itself can't suffer from beauty, nor from charity, nor from intelligence . . . It's obliged to suffer from what makes us suffer.

J-LG: And Marie is, if I dare say it, another donkey.

RB: She's the character parallel to the donkey, who ends up suffering the way it suffers. So, for instance, with avarice. She's denied food (she's even forced to steal a jar of jam), just as the donkey is refused oats. She is subjected to the same things as he is. She is subjected to lust as well. She is subjected . . . not exactly to rape, maybe, but something close to it. So you see what I was trying to do. And it was very difficult, because the two schemes that I just described to you couldn't be only the effect of a system, they couldn't appear to be systematic. And also, the donkey couldn't simply return as a leitmotif with its judicious eye, observing what humanity does. That was the danger. I had to achieve something fairly regulated but that wouldn't seem so, in the same way that these vices shouldn't give the sense of existing just as vices that disturb the donkey. If I said "vices" it's because in the beginning these really were vices, ones from which the donkey was made to suffer; but I softened the systematic quality of this in order to refine the construction, the composition.

J-LG: And the character of Arnold? If we had to define him . . . Not that I want to define him necessarily, but if we had to, if we were forced to give clues to his character, or to make him represent certain things rather than other things, what would we say? What would you say?

RB: He represents, to a degree, intoxication — in other words, gluttony — but he also represents grandeur, a kind of freedom among men.

J-LG: Yes. Because when you see him, you're forced to think about some very particular things . . . Also, he looks a bit like Christ.

RB: Yes, but that wasn't on purpose. Not at all. He represented intoxication above all; because when he hasn't drunk, he's sweet, and when he has drunk, he fights with the donkey, revealing one of the things that must be the most incomprehensible for an animal — the way the same person can be modified by the consumption of a bottle of liquid. And that — it's something that must stupefy animals, that must make them suffer dearly. At the same time, I immediately sensed the grandeur of his character. And maybe also a parallelism with the donkey: they share a particular sensibility about things. Something we find, maybe, in certain animals that are very sensitive to objects. You know how animals can falter, can swerve from an object when they see it. I take this to mean that objects count a lot for animals; more, maybe, than they do for us, who are used to them and who, unfortunately, don't always pay attention to them. So there is parallelism there too. I intuited it, but I wasn't going after it. All of this happened spontaneously. I didn't want to be too systematic. But as soon as there was grandeur, of course I sensed it and didn't push it away, I let it happen. It's interesting to start with a fairly strict outline, and then to discover the ways in which we might manipulate it, how we end up with something suppler, and yet, at the same time, intuitive.

J-LG: I'm suddenly reminded that you're a person who deeply loves painting.

RB: I am a painter. And maybe that's a way to return to your idea. Because I'm not really a writer. I write, yes, but I force myself to write and so I write, I'm aware of this, a bit the way I paint (or, to be more accurate, painted, because I no longer paint, but I will paint again), that is to say that I'm not capable of typing until the ribbon runs out; I am capable of writing from left to right, and of aligning a few words in this way, but I can't do it for a long time, not continuously. For me, when I write, I write the way I apply color: I put a bit to the left, and a bit to the right, a bit in the middle; I stop, I start again . . . and it's only after something has been written and I'm no longer annihilated by the blank page that I can start to fill in the holes. So, not a whole ribbon at once. And that's how the film was made. I mean that I placed some things at the beginning, some things at the end, and some other things in the middle; I took notes when I thought of it — every year, every other year — and then it was in the act of reassembling all of this that the film was made, much the way the final arrangement of colors in a painting expresses the relations between things. But the risk of this film was a lack of unity. Fortunately, I was well aware of the danger dispersion poses to a film (it's the biggest danger, the trap almost every film falls into). I had a serious fear that mine wouldn't become unified. I knew that unity, in this case, would be hard won. Maybe it is less unified than my other films: but maybe, as you said a moment ago, this is an advantage.

J-LG: I only wanted to say that your other films followed straight lines, and that this one is made more of concentric circles — if I had to come up with an image for comparison's sake — concentric circles that intersect each other.

RB: I know this film has less unity than the others, but I've done what I can for it by presenting it as one thing, thinking that because of the donkey it would wind up forming a kind of unity on its own. I couldn't have done otherwise. The film also has, perhaps, a unity of vision, a unity of angle, a unity in the way I cut the scenes and shots together . . . Because anything can bestow unity. Even a way of speaking. In fact, that's what I'm always looking for. Almost all the people in the film talk in the same way; unity is, essentially, revealed through form.

J-LG: And how do you see questions of form? I know we don't think about it much, at least not during the making of a film, but we do think about it after. For example, when we're editing, we aren't thinking about it. At the same time, I always ask myself afterward: Why did I cut there instead of there? And for others, too, it's the only thing I can never understand: Why they cut, why they don't cut.

RB: Like you, I think it's something that has to become purely intuitive. If it isn't intuitive, it's going to be bad. In any case, for me that's the most important thing.

J-LG: And yet it must be possible to analyze it . . .

RB: Well, I see my film only through the lens of form. It's strange: When I watch it again, I see only the shots. I have no idea whether the film is emotionally effective or not.

J-LG: I think it takes a very long time to be able to watch one of your own films. One day, you'll find yourself in a small village, in Japan or somewhere, and then you'll be able to re-watch your film. At that moment, you'll be able to encounter it as an unknown object, the way a normal viewer would. But I think it really takes a very long time. Also, you can't be expecting to see it.

RB: To return for a moment: in my own work I attach a great importance to form. An enormous importance. And I believe that form generates rhythm. And that rhythm is all-powerful. It's the primary thing. Even when you add a voice-over, this voice-over is initially seen, is felt, as a rhythm. Next, there's color: it can be warm or cold. And then there's meaning. But the meaning arrives last. Now, I believe the question of accessibility to the public is above all one of rhythm. I'm convinced of it. So in the composition of a shot, of a sequence, rhythm comes first. But this composition can't be premeditated, it has to be purely intuited. It happens, for example, when we're shooting outside, and we're faced with an absolutely unknown setting the night before. When confronted with the unknown, we're forced to improvise. And this is a good thing: the obligation to find, and to find quickly, a new equilibrium for the shot we're creating. So even then, I don't believe in thinking too much. Overthinking reduces everything to the mere execution of a plan. Things need to happen impulsively.

J-LG: Your ideas about cinema — if you have any — have they evolved, and in what way? How do you film now, compared to yesterday or the day before yesterday? And how do you think about cinema after your last film? For me, I now realize that I did have, three or four years ago, ideas about cinema. But I don't have any now. And to change that, I need to continue to make films, so I can generate some new ideas for myself. Let me ask you, then: How do you see yourself in relation to cinema? I don't mean in relation to the kind of cinema that exists, but in relation to the art of cinema?

RB: Yes, but I should first tell you how I see myself in relation to what's being made. Just yesterday someone asked me (it's a reproach that's made of me sometimes, perhaps without meaning to be one but nevertheless . . .): "Why don't you ever go see films?" And it's true: I don't go to see them. It's because they frighten me. That's the only reason. Because I sense I'm moving away from them, from contemporary films, more and more each day. And this frightens me because I see that these films are being embraced by the public, and I don't foresee that happening with my films. So I'm afraid. Afraid to propose something to a public with a sensibility for another thing, a public that will be insensitive to what I'm doing. But also, it's good for me see a contemporary film from time to time. To see just how big the difference is. So I'm realizing that without meaning to, I've distanced myself more and more from a kind of cinema I feel is moving in the wrong direction — that's settling deeper into music-hall, into filmed theater, that's losing its interest (not only its interest, but its power) — and heading for catastrophe. It isn't that the films are too expensive, or that television poses a threat, but simply that that kind of cinema isn't an art, though it pretends to be one; it's a false art, trying to express itself using the form of another art. There's nothing worse or more ineffectual than that kind of art. As for what I'm trying to do myself, with these images and sounds, of course I feel I'm right and they're wrong. But I also get the sense that I have access to too many means, which I try to pare down, reduce (for what also kills cinema is the profusion of means, the abundance; abundance can never bring anything to art). That moreover, I'm in possession of extraordinary means all my own.

J-LG: You were speaking a moment ago of actors . . .

RB: There's an unbridgeable gap between an actor — even one who is trying to forget himself, to not control himself — and a person who has no experience being on film, no experience with the theater, a person used as brute material, who doesn't know what he is and who ends up giving what he never intended to give to anyone.

The way you capture emotion is through practicing scales, through playing in the most regular, mechanical way. Not by trying to force emotion, the way a virtuoso does. That's what I'm trying to say: an actor is a virtuoso. Instead of giving you the exact thing that you can feel, actors force their emotion on top of it, as if to tell you, "Here's how you should feel things!"

J-LG: It's as if a painter hired an actor instead of a model. As if he said to himself: instead of using this washerwoman, let's hire a great actress who will pose much better than this woman. It that sense, I completely understand you.

RB: And I want to be clear that this is not at all to diminish the work of actors. To the contrary, I have an enormous amount of admiration for great actors. I think theater is marvelous! And I think it's extraordinary, to learn how to create with your body. But let's not confuse things! People have said to me, "You don't use actors because you're proud." But what does that mean? I reply: "Do you think it's fun for me not to use actors?" Not only is it not fun, it's an incredible amount of work. And I've only made six or seven films. . . . Do you think I like being stalled all the time? Not working? I don't like it at all! I want to work, I would much prefer to be working all the time. And why haven't I been able to make more films? Because I don't use actors! Because by making that choice, I have separated myself from the commercial aspect of cinema, which is based on movie stars. So to say a thing like that: It's absurd!

J-LG: It must be said that the theater is older. It's existed for so long, we have a hard time not referring to it.

RB: Yes, and to think that it still exists. And those people who think, who sometimes write (I've even read this recently) that silent films are the only pure cinema! Imagine!

J-LG: They say that, yes, but that doesn't change the fact that when they watch a silent film they can't stand it!

RB: And what I was saying goes a lot further: There was never such a thing as silent film! It never existed! Because people still spoke, they just spoke into the void, we didn't hear what they were saying. So please don't say that we created a silent style! It's absurd. There were a few, like Chaplin and Keaton, who did create a style, a marvelous style of gestures and mimicry, but the style they gave their films was not a "silent style." I will address this too in my book. I do believe it's the time for it. But to work any more on it: it won't be quick. And whenever I try, I fail. Because a film, for me, it isn't just the work on the film, but it's being inside the film. I think about it. Everything I experience, everything I see, is from inside the film, gets processed through the film. To leave it is to travel to a different country. So I'm not getting anywhere with the book. And yet, I need to. I'm very impatient to write it. I believe now is the time. Because cinema is collapsing!! And what a fall it will be.

Yesterday I went to the Cinerama. Because, you know, you can get there by way of Studiorama. And often I'll sit in the balcony, where it's empty, and from where you can see the immense screen that covers every surface. It has quite an effect! . . . And the trains that leave from one end and come straight toward you! It's magnificent, this invention! People leave from your right pocket and return to your left pocket! And when it's a train . . . it's marvelous! So, yesterday, in the balcony — and there was a pair of lovers who, by the way, weren't watching the film at all — yesterday I was in this room where a certain kind of cinema takes place, and I was stupefied!

J-LG: The same thing happened to me four days ago at Studiorama. I went to the restrooms, which are on the same floor of the Cinerama balcony, and I went in and took a seat there. And it's true: You enter the theater. . . . I saw a few frames of the film: madmen writhing around. That's when you realize that cinema is not the same thing as cinematography.

RB: Absolutely! That's what it is now, the cinema.

RB: Terrible feelings! Feelings of absolute falsehood, as if falsehood had been captured by a miraculous machine, and then amplified. For what you have is the deliberate amplification of the false, so that it will really get into the audience's head. And when they have that in their head, I guarantee it will be hard to make them leave!

I think the disparity really comes down to this: the cinema copies life (or photography), whereas I recreate life from elements that are as crude as possible.

J-LG: We could further specify what was just said about cinematography, as opposed to cinema: that it is more moralistic.

RB: Or, if you like, that it's more like the system of poetry. Take the most disparate elements in the world, and bring them together in a certain order that is not the usual order but your own order. The elements must be raw. The cinema, in contrast, recopies life using actors and films this copy of life. So we are absolutely not on the same terrain. When you talk about the contemporary, or contemporaneity: I don't think about it at all. And if reference to the era comes up, well then maybe I think about it, in the sense that I might say to myself, in fact, that I'd rather be outside of the era. From the moment when I'm trying to go deeply into the interior of a living being, this becomes one of the dangers I need to avoid. Here, I'm adding another thing that I've never said and that's important: the biggest difficulty with what I'm trying to do by penetrating into the unknown essence of ourselves . . . the greatest difficulty is that my means are exterior means and thus function in relation to appearances, all appearances: the appearance of the person himself, and the appearance of what surrounds him. The great difficulty is, then, to remain in the interior, without moving to the exterior; it's to avoid producing a sudden, terrible sundering. And that's what happens to me sometimes; and when it does, I try to repair my mistake.

I'll take an example from my film: the misbehaving boys. When they throw oil on the road and the cars skid, at that moment I'm completely exterior. And it's a great danger. So I correct myself as well as I can to refocus on what's going on inside these boys.

J-LG: There are two tendencies that you have, and I don't know which one you would think corresponds most to who you are: You are, on the one hand, a humanist, and on the other hand, an inquisitor. Are these two things reconcilable, or is there a . . . ?

RB: An inquisitor? In what sense? Not in the sense of . . .

J-LG: Ah, not in the sense of the Gestapo, of course! But in a sense, let us say . . .

RB: Ah! No. No.

J-LG: Or, let's say instead: Jansenist.

RB: Jansenist? Well, in the sense of the starkness . . . You can also find Jansenism — and this is an impression I have myself — in the idea that our life is made both of predestination (Jansenism, in effect) and of chance. Chance was perhaps, without my realizing it, the point of departure for the film.

To be precise, the point of departure was a sudden vision of a film in which the donkey is the main character.

J-LG: Like Dostoevsky — whom you quote in the film — who saw a donkey and had a sudden revelation. And that little passage, in just a few words, says so much . . .

RB: Yes, It's marvelous. You think I should have used it as an epigraph?

J-LG: No . . . No. But it's good to have put it inside . . .

RB: Yes. I was awestruck when I read that. But I read it after thinking about the donkey, you know. In fact . . . the truth is I had read The Idiot, but I hadn't paid much attention. And then, two or three years ago, while rereading The Idiot, I said to myself: this passage! What an incredible idea!

J-LG: That's it: you came to the idea just as Myshkin did . . .

RB: Absolutely admirable to make an idiot be informed by an animal, to make him see life through an animal — one that passes for an idiot, but has such intelligence! And to compare this idiot (but you know what he is: you know he is actually more intelligent and refined than anyone), to compare him to the animal that passes for idiotic and that is in fact the most intelligent and refined of all. It's magnificent! Magnificent: this idea to create an idiot after seeing a donkey and hearing him bray, say: "I understand now!" That is extraordinary, it's genius. But that isn't the idea of my film. The idea may have arrived by way of aesthetics. Because I'm a painter. The head of a donkey seems, to me, to be worth admiring. Yes, aesthetics, without a doubt. But suddenly I envisioned the film. Then I lost it, and the next morning, when I tried to get back to it. . . . Later, I found it again.

J-LG: But when you were young, you hadn't seen . . .

RB: Yes! I had seen tons of donkeys. Yes, of course, I had seen them . . . And childhood plays an important role too, of course.

J-LG: Roger Leenhardt also saw plenty of donkeys in his youth . . .

RB: But you know, the donkey is a marvelous animal. And there's another thing I can tell you: I had a serious fear, not only in writing, but in shooting the film, that the donkey would not become a character like the others, that it would read as a trained donkey, a trick donkey. So I chose to use a donkey that knew how to do exactly nothing. Not even how to pull a wagon. In fact, I had a very difficult time training it to pull a wagon for the film. Everything I thought it would do for me it refused to do, and all that I thought it would refuse it accomplished. To pull a wagon, for example. We think donkeys do that. But it isn't true! And I also asked myself: When will I need to train it for the circus? At some point I stopped the film and gave the idiot donkey back to the trainer so that we could shoot the circus scenes. I had to wait two months to shoot those scenes!

J-LG: Yes, in the circus scene he really had to know how to click his heels!

RB: So I waited two months for the donkey to be ready. In fact, that's why the film was a bit late. But at the beginning I was very worried. I had wanted for this animal, though just an animal, to be raw material as well. And maybe the donkey's expressions at certain moments, when he's looking at the other animals for example, or at the characters, maybe they would have been different if he'd been a trained, fully tame donkey. But I discovered, or verified rather, something that contradicts everything we think we know about donkeys (and even though this didn't surprise me, it did impress me): the donkey is not a stubborn animal. Or if it is, it's only because it's so much more sensitive than others. When a donkey is brutalized, it will freeze and stop reacting. The trainer (an intelligent man and an excellent trainer) told me when I asked if donkeys are harder to train than horses: It's exactly the opposite: horses, which are stupid, are fairly hard to train, but donkeys, as soon as you tell them something, as long as you don't make the wrong gesture, they know exactly what they're supposed to do.

J-LG: I'm thinking now of a different point of view, a formal one: the angle, or the width, you had to use to film the donkey's expressions so that we can see them.

RB: Of course.

J-LG: The donkey looks to the side, while our eyes face front.

RB: Yes, of course.

J-LG: And you had to be certain . . . You couldn't be a millimeter too far to the left or the right . . .

RB: There's another thing too: With this animal I didn't experience the obstacles I expected, but did experience other obstacles of an entirely different order. For example, when I shot the exteriors in the mountains or around Paris, I was using a small camera that made some noise. As soon as the camera came too close to the donkey, the noise prevented it from doing anything at all. You can imagine how much of a challenge this presented! So I had to distract the donkey in order to capture his expression. But I was also able, at times, to make use of his attention to the noise to capture other expressions. In any case, this kind of challenge, plus the rain, it all made the filming very difficult and I was forced to improvise. I was constantly having to change my plan. I couldn't do this thing at that location; I had to do some other thing at some other location. For the whole final scene, the death of the donkey, I was terribly worried that I wouldn't get what I wanted. I had such trouble getting the donkey to do what he was supposed to do, what I needed him to do. And he did it only once, but at least he did it. And sometimes I had to provoke him using strategies that weren't the ones I'd planned. This occurs at the moment in the film when the donkey hears the bells and perks up his ears. It only worked because I caught something at the last minute, when he gave me the reaction I needed. He did it only once, but it was wonderful. That's a kind of joy that filming can sometimes deliver. You're in deep trouble, and then a miracle happens.

And I love the title. Someone said to me, "I don't like the rhyme in the title." I replied, "But it's marvelous, a rhymed title."

J-LG: Yes, a title like that is a marvelous thing.

RB: And, on top of that, how appropriate it is for the film: By chance Balthazar . . .Which brings us back to Jansenism, because I really do believe that our life is made up of both predestination and chance. When we study the lives of individuals, especially of exceptional individuals, it's something we see very clearly. I'm thinking of the life of Saint Ignatius, for example, about whom I once thought I would make a film (I won't). Well, in studying the curious life of this man who founded the greatest religious order (the most popular, in any case, and one that spread all over the world). In studying his life, you get the sense that he was predestined for it, and yet all along his path to founding the order there are these chance events, chance encounters, through which you can see how, little by little, he came to understand what he had to do.

It's also the case, to some degree, with the escapee in A Man Escaped. He's heading toward a certain point. He has absolutely no idea what awaits him on the other side. He gets there. And once there, he has to choose. He chooses. And he arrives at another point. And there, again, chance makes him choose something else.

Because essentially, if you pay enough attention you see that things resemble each other in life. Even the simplest life, the most mundane, resembles another life, another human being. But with accidents, with different strokes of luck . . . In the case of great men, it's clear because we talk about them, because we know the details of their lives, but I am persuaded that all of our lives are made in exactly the same way: out of predestination and chance. We're well aware that the essence of who we are is already formed by the age of five or six. By that point it's more or less finished. At twelve or thirteen, it starts to become visible. And after that we continue to be what we've been, taking advantage of different opportunities. We use them to cultivate what was already in us, what — if we don't get the chance to cultivate it — might not be visible about us. I'm convinced that we're surrounded by people with talent and genius, I'm certain of it, but the chances that life give us . . . it takes so many coincidences for a man to be able to make use of his genius.

I have a feeling that people are much more intelligent, much more gifted; but that life crushes them. Immediately. They get crushed because nothing is more frightening than talent or genius. It makes us uneasy. Parents fear it. So they squash it. And in animals, there must be some very smart ones that we destroy with training, by beating them. . . .

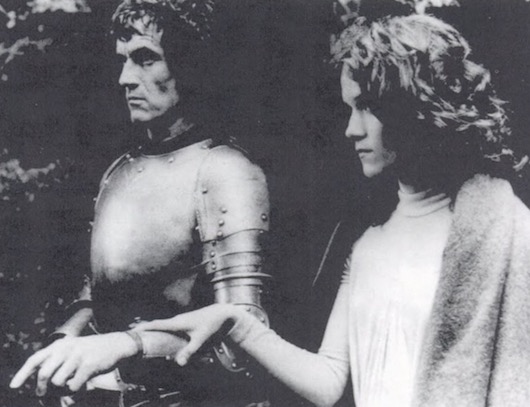

J-LG: As far as your projects go, are you still thinking about Lancelot?

RB: Yes, I hope to make that film. But in two languages. In French, of course, and in English. It's exactly the type of film that should be made in two languages (and I should really also make it in German), because the same legend exists in our mythology and in the Anglo-Saxon. Plus those stories were originally written in the two languages. We have the transcription of Chevalier de la charrette. Then there came Perceval le Gallois, and also Tristan . . . So these are the first poems, sung and recited, that emerged from the legend of the Grail; later written down by scribes and by monks who added elements from their religious orders. What interests me is this: to revive an old legend that is known all over Europe. And if I can make the film in English, I'll have a little more money in the beginning, which is important since I can't make this film with exclusively French money . . . unless I hire movie stars. French movie stars. And I don't want to. But I do hope I'll be able to make it in the two languages.

However, I won't be emphasizing the fairy-tale aspect of the legend — I mean the actual fairies, Merlin etc. Instead I will try to transpose that element into the domain of emotion: to show the ways in which emotion modifies the very air we breathe. In any case, I think we wouldn't believe in fairies of that kind today; and in film, belief is crucial. So I'll try to transpose the fairy side of things into emotion and make it so that the emotions have an effect on the incidents that occur in the film. So if I can inspire somebody's confidence, I'll get to work.

And I would also like — as an exercise — to make La Nouvelle histoire de Mouchette. It's a difficult one, of course.

J-LG: The character of Marie in Au hasard Balthazar resembles Chantal in Bernanos's other novel, La Joie, which at one point I wanted to make into a film myself.

RB: Yes, perhaps. I'm sure I've read La Joie, but you know I don't read many novels . . . But I must have read at least some passages from it. The ending, maybe . . . And the novel ends, if I remember correctly, with the death of a priest.

J-LG: Yes, that's right.

RB: But the character in La nouvelle histoire de Mouchette is quite wonderful, in that it's still about childhood — that period between childhood and adolescence — shown in all its difficulty. Which is not to say inanity, but really something like catastrophe. And that's admirable, and it's what I would try to do. And rather than spreading out (I've always tried not to spread myself too thin) among a proliferation of lives and people, I'll try to remain constantly, devotedly, on one face — the face of this young girl — to observe her reactions. And, yes, I'll choose the girl who is most awkward, the least like an actress, the least like a performer (which children, especially girls, so often are, and incorrigibly so). Basically I'll take the most awkward girl I can find and try to get from her everything that she'll think I can't. That's why this interests me. And why, obviously, the camera won't stray from her.

J-LG: Would you consider giving her an accent? Bernanos talks about her horrible Picardie accent.

RB: No. Absolutely not. I don't like accents . . . Bernanos has wonderful flashes of brilliance. There are two or three things that he discovers, that he says about the girl, that are extraordinary. Not having to do with psychology . . .

J-LG: Yes, I remember. He says that just as they're talking to her about death, it's as if they've told her that she gets to be a grand dame under Louis XIV . . . I mean, there's a fabulous elision there. And it's true, it's not psychology, but it's something so profound.

RB: It's not psychology, but I think that's the point (and we will return to what interests us so much about that). Psychology is something we know well now, it's accepted, familiar; but there could be a whole psychology to extract from the kind of cinematography I imagine, in which the unknown happens to us all the time, in which this unknown is recorded, and this happens because a mechanical structure has caused it to appear. And not because we wanted to find it (this unknown thing) in advance; which is impossible, because the unknown reveals itself rather than being revealed. But I think we shouldn't be making psychological analyses; and psychology is too a priori. You have to paint. It's through painting that things will happen.

J-LG: There's an old expression we no longer use: the painting of feelings. That's what you're doing.

RB: Painting, or writing (in this case, it's the same thing). And in any case, yes, more than psychology, I think it's painting.

1966