False Notes

The letters of Henry James from Italy paint a disturbing and often contradictory picture. On one hand you have an educated observer open to a variety of impressions and situations detailing events. On the other, Henry seems oblivious to much of what he experiences, so much so that you have to wonder what percentage of the world he encounters on even footing. In the following selections, James details his view of Italy — it is the view of Englishman, granted, but an appreciative one.

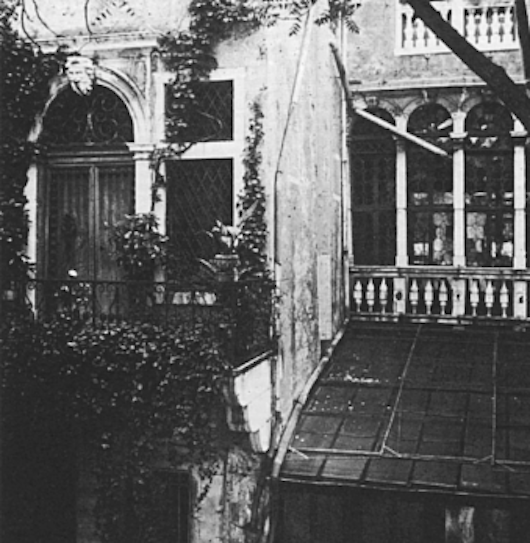

The first month I was in Florence I had a villa at Bellosguardo, kindly sublet to me by a friend (Constance Fenimore Woolson the novelist—an excellent woman, of whom I am very fond, though she is almost impracticably deaf), who had taken it for three years and was not yet ready to go into it, having another on her hands.

A cook went with it—a venerable—and veritable chef—so that I was very comfortable—and blissfully lifted out of that little simmering social pot—a not very savoury human broth—into which Florence resolves itself today.

It is a pity it is personally so tiresome, for (allowing for the comparative ugliness of its winter phase, with hard cold and dusty tramontana) it had never seemed to me, naturally and artistically, more delightful. And the views from the villas on the hills (I was at a good many) are as beautiful—really—as your memory must tell you. On January 1st my friend came into her villa and I descended into Florence—where (I am told) I went “out” a good deal. Why, I don’t know—as it was very exactly what I had left London not to do.

I am also told I was “lionized”—and the wherefore of this I know still less. On reflection, in fact, I greatly doubt it. But I did see a great many people; too many, for what they were. I won’t tell you their names, or more than that they were members of the queer, promiscuous polyglot (most polyglot in the world) Florentine society.

+

Venice is wintry yet and so little terne, in consequence; also the calles and campos impress the sense with a kind of glutinous, malodorous damp. But it is Venice, none the less, and it is a ravishment to be here and to think that every week, at this season, will bring out a little more of the colour. I have a hope, if I stay in Italy late enough, of going down to Rome for ten days in May—when the damaging crowd shall have taken itself off. I dream then of also taking a little tour of old towns in Tuscany. If I am able to do this I shall certainly give you news of Rome.

+

I enjoyed my absence, and I shall endeavour to repeat it every year, for the future, on a smaller scale: that is, to leave London, not at the beginning of the winter but at the end, by the mid-April, and take the period of the insufferable Season regularly in Italy. It was a great satisfaction to me to find that I am as fond of that dear country as I ever was—and that its infinite charm and interest are one of the things in life to be most relied upon. I was afraid that the dryness of age—which drains us of so many sentiments—had reduced my old tendresse to a mere memory. But no—it is really so much in my pocket, as it were, to feel that Italy is always there.

+

De Vere Gardens always follows me.

+

There are many things I must ask you to excuse. One of them is this paper from the village grocer of an unsophisticated Bavarian valley. The others I will tell you when we next meet. Not that they matter much; for you won’t excuse them—you never do. But I have your commands to write and tell you “all about” something or other—I think it was Venice—and at any rate Venice will do. Venice always does.

+

This is a delightful moment to be in Italy, and really nowadays, the only right one—for the herd of tourists has departed, the scramble at the stations is no more, and one seems alone with the dear old land, who at the same time, seems alone with herself. I am happy to say that I am as fond as ever of this tender little Florence, where it doesn’t seem a false note even to be staying with an “American doctor.” My friend Baldwin is a charming and glowing little man, who, coming here eight or ten years ago, has made himself a first place, and who seems to consider it a blessing to him that I should abide a few days in his house.

+

When, three mornings ago, I rose early, to take the train for Florence, and in the cool, fresh 7 o’clock light, was rowed through the delicious half-stirred place and the imbroglio of little silent plashing waterways to the station, it was really heartbreaking to come away—to come out into the dust and banalité of the rest of the world. (Venice clings closer to one by its dustlessness than perhaps by any other one charm.) But already the sweetness of Florence tastes. I am, however, seriously thinking, or rather dreaming, of putting my hand on some little cheap permanent refuge in Venice—some little perch over the water, with a bed and a table in it, to call one’s own and come away to, without the interposition of luggage and hotels, whenever the weight of London, at certain times, is no longer to be borne.

+

At Verona I collapsed upon my old hotel—which, however, this time I found excellent and not exceptionally dear.

Some day you might do worse than try it—the woods, the walks, the views, the excursions, the places to stroll in, and sit, and spend the day in the open air, all being, apparently, exquisite and extremely numerous. The only blot is that one has to make sure of quarters a long time in advance—unless one stays with Mme Peruzzi: a privilege that I am actually engaged in wriggling out of.

+

Italy is already a dream and Venice a superstition.

I have been here (in this particular desolation,) since yesterday noon, intently occupied in realizing that I am an uncle. It is very serious—but I am fully taking it in. I don’t see as yet, how long I shall remain one—but sufficient unto the day are the nephews thereof.

I can only, for all sorts of practical reasons, live in London, and must always keep an habitation “mounted” there. But whenever I have been in Venice (especially the last two or three times), I have felt the all but irresistible desire to put my hand on some modest pied-à-terre there—modest enough to be compatible with the retention of my London place, which is rather expensive; and such as I might leave standing empty for months together—without scruple—in my absence, and deposit superfluous luggage in, when I wished to “visit” Italy. This humble dream I still cherish—but it is most vivid when I’m on the spot—i.e. Venice; it fades a little when I’m not there.

I rejoice in everything that may be comfortable in your situation or interesting in your adventures.

1869-1890