My Only Advice

In every relationship, romantic or otherwise, one of the two people feels slightly closer to the other, if only by a matter of degrees. So it was with Gustave Flaubert and his hypochrondriac, flaky friend Ivan Turgenev. These two barnacles met when Flaubert was 40 and Turgenev was three years older. From the tenor of their conversations, which Flaubert seemed to treasure above all else, we can deduce that their spirits remained substantially youthful. Flaubert's self-professed love of literature was so all-encompassing it almost crowded out other parts of himself; Turgenev shared his friend's basic interest but saw the underlying reality for what it was. (Turgenev called his friend, "the only man in existence really devoted to literature.")

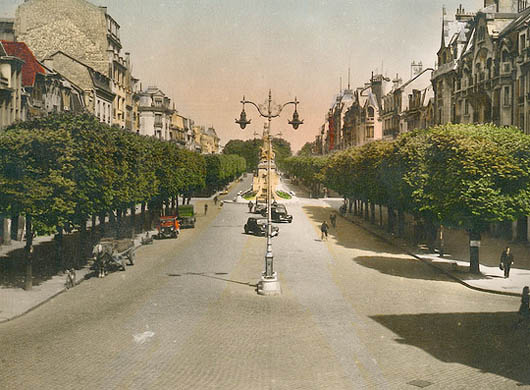

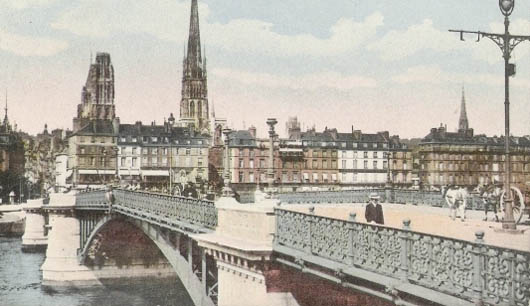

Turgenev would visit Flaubert at his retreat in Croisset in the summer, or in Paris during the winter season. Many of the hours they passed together consisted of Flaubert reading his novels or plays aloud, a difficult task even for one of his most central admirers. The written correspondence between the two in the 1860s leaves the mortal plane behind; it can be classified as the first bubbles of modernity to enter the universe.

March 1863

My dear Turgenev,

Your letter was most kind and you are too modest. For I have just read your latest book. I found your essential qualities in it, and more intense, more rarified than ever.

What I admire above all is the distinguished quality of your art — a wonderful thing. You manage to ring true yet avoid banality, to be sentimental without morbidity, and comic without being at all low. Without looking for high drama, you achieve it none the less by the sheer professionalism of your tragic effects. You seem very casual, but you have great skill, 'the skin of the fox combined with that of the lion', as Montaigne said.

Elena's is a fine story. I like this character, as well as Shubin and all the others. While reading you one says to oneself 'I've experienced that'. Thus I believe that page 51 will be felt with greater intensity by no one than by me. What a psychologist! But I'd need many lines to express all my thoughts on that.

As for your First Love, I understand it all the better for its being the story of one of my closest friends. All old romantics (and I who slept with a dagger under my pillow am one) should be grateful to you for this little story that has so much to say about their youth! What a real live girl Zinochka is.

The creation of women is one of your strong points. They are both ideal and real. They have the attraction of saintliness. But what dominates this work, indeed the whole collection, is the two lines: "I had no bad feelings towards my father. On the contrary he had, so to speak, increased in stature in my eyes." That strikes me as being startlingly profound. Will people pick it up? I don't know. But for me, it is sublime.

Yes, dear colleague, I hope that our relationship will not stand still, and that our mutual sympathy will tum into friendship.

In the meantime, one thousand handshakes from your

Gustave Flaubert

April 1863

My dear colleague,

I don't need, I hope, to tell you how much pleasure your second letter gave me — and more than pleasure! If I didn't reply straightaway, it was because I had to extricate myself from a host of disagreeable little matters that made me ill-humoured and lazy at the same time. These miseries continue, but my conscience will not permit me to delay any longer. I have been counting, and still do, on your indulgence — and above all I want to thank you and shake you by the hand.

I am very glad to have your approval and you should be convinced of it: I well know that an artist and man of goodwill such as yourself reads a host of things between the lines of a book, for which he generously appreciates the author's effort: but it doesn't make any difference. Praise coming from you is worth gold — and I pocket it with pride and gratitude.

Shall we not see each other during the summer? An hour of good, frank conversation is worth a hundred letters. I'm leaving Paris in a week's time to go and settle in Baden. Will you not come there? There are trees there such as I've seen nowhere else — and right on the tops of the mountains. The atmosphere is young and vigorous and it's poetic and gracious at the same time. It does a power of good to your eyes and to your soul. When you sit at the foot of one of these giants, it seems as if you take in some of its sap - and it's good and beneficial. Really, come to Baden, even if it were only for a few days. You will take away with you some wonderful colours for your palette.

Before I leave, you will receive a book by me which has just been published. I am cramming you full — but you are partly to blame.

A thousand friendly greetings, keep well, work well, and come to Baden.

Yours

I. Turgenev

Turgenev,

Cram me full then, dear colleague! I await your book impatiently and I shall read it with delight, I am sure.

I also have had a number of little aggravations just lately. The affinity between us is complete, you see.

I don't think I shall be able to go to Baden, because I shall have several obligations that will disturb my routine this summer. When will you be back? And send me your address.

I shall spend the whole of June or the whole of August in Paris. In any case, we shall see each other next winter.

A thousand very long and very vigorous handshakes from your

Gustave Flaubert

May 1868

My dear friend,

I'm very grateful to you for thinking of writing to me. Your letter gave me much pleasure — for it re-established relations between us and because it showed that you liked my book.

These days every single artist has something of the critic in him.

The artist is very great in you — and you know how much I love and admire it; but I also have a high opinion of the critic and I am very happy to have his approval. I well know that your friendship for me counts for something in all this: but I have the feeling that a master has stood in front of my picture, has looked at it and has nodded his head with an air of satisfaction. Well, I'll say again that this has given me great pleasure.

I was very sorry not to have seen you in Paris — I only stayed there three days, and I regret even more that you are not coming to Baden this year. Your novel has you in harness — that's good — I await it with the greatest impatience — but could you not take a few days rest, to the profit of your friends here? Since the first time I saw you (you know, in a sort of inn on the other bank of the Seine) I have felt a great liking for you — there are few men, particularly French men, with whom I feel so relaxed and at ease and yet at the same time so stimulated. It seems to me that I could talk to you for weeks on end, but then we are a pair of moles burrowing away in the same direction.

All this means that I should be very glad to see you. I'm leaving for Russia in a fortnight's time, but I shan't stay there long, and I shall be back by the end of July — and I shall go to Paris to see my daughter who will probably have made me a grandfather by then. I shall be game enough to come and chase after you even at home — if you are there. Or will you come to Paris? But I must see you.

In the meantime I wish you good fortune. The living, human truth that you pursue indefatigably can only be captured on good days. You have had some - you will have more — and many of them.

Keep well; I also embrace you — and with true friendship.

I. Turgenev

July 1868

My dear Turgenev,

This is simply to remind you of your promise. You were supposed to be in Paris at the end of July or the beginning of August. As for me, I am here, and I await you.

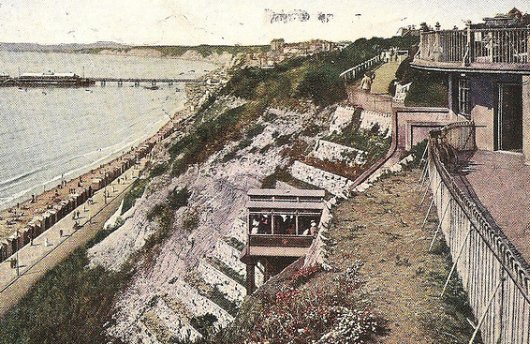

So as to avoid your making unnecessary arrangements, here is my programme: from 30 July (next Thursday) until August I shall be at Saint-Gratien at the Princess Mathilde's. Then I shall return to Paris for two days. I shall then spend another two days at Dieppe at one of my nieces. Then I shall return to Croisset, to get on with my book.

We must spend a few good hours together.

I embrace you wishing you cooler weather than we're having in Paris, and I remain yours

G. Flaubert

August 1868

My dear friend,

I have waited until now to reply to your kind little note, because Iwas still hoping to be able to announce my arrival; but my devilish gout is obstinately refusing to leave me, and I cannot yet contemplate any kind of long journey. It's annoying — but what can I do about it? I shall come as soon as I can; and in the meantime I embrace you and beg you to present my respects to your mother, whom I shall be very happy to meet.

Work hard in the meantime.

I. Turgenev

November 1868

My dear friend,

The cheese has just arrived; I shall take it to Baden with me, and with every mouthful we shall think of Croisset and of the delightful day I spent there. Decidedly I feel that there is a real affinity between the two of us.

If all of your novel is as good as the extracts you read to me, you will have written a masterpiece, I'm telling you.

I don't know if you've read the book I'm sending you; in any case, put it on one of the shelves of your library.

Present my respects to your mother — and let me embrace you.

Your

I. Turgenev

P. S. My address is: Carlsruhe, poste restante. It would be very kind if you were to send me a photograph of yourself. Here is one of me that looks very forbidding.

P.P.S. Find another title. Sentimental Education is wrong.

January 1869

But I must have news of you, my dear friend. Let's see now — in two words: where are you — and how is the novel going? I am writing to you at Croisset, and perhaps you are in Paris, sniffing out what's new.

In any case, I don't think you'll stay there long.

I have not yet thanked you for the photograph, which makes you look very military and well groomed — but it's you all right — and it's always good to look at it. Why don't you have some good ones taken?

I have often thought of Croisset, and I think to myself that it's a nest to fledge songbirds in. As for me, I have done almost nothing. I have embarked on a task that I find repugnant and I am floundering about sadly in it. There's no going back, but when it's finished, I shall give a great sigh of relief! It's a sort of anthology of literary reminiscences that I promised my publisher; I have never worked in that field and it's not at all amusing. Oh! Two hours of being Sainte-Beuve! I'd like to know if he enjoys it very much.

My best greetings to your honourable mother, who seems to me the best possible of mamas one could imagine, and a good vigorous handshake to you.

Your

I. Turgenev

P. S. I am here for the whole winter because my friends the Viardotl are here. It's not very gay, Carlsruhe, but it's better than its reputation. I shall come to Paris towards the end of March.

My dear friend,

Yes, people have certainly been unfair to you, but this is the time to brace yourself and hurl a masterpiece at the reading public. Your Anthony could be such a projectile. Don't tarry too long over it, that's my refrain. Don't forget that people judge you according to the standards that you yourself have established, and you're bearing the weight of your past. You have energy; el hombre debe ser feroz as the Spanish proverb says — and artists especially. Even if your book has only gripped a dozen people of any worth — then that is enough. You understand I'm saying all this not to console you, but to spur you on.

I have been here for about ten days — and my sole preoccupation is keeping warm. The houses are badly built here, and the iron stoves are useless. You'll see a very little thing by me in the March edition of the Revue des 2 Mondes. It's nothing very much. I'm working on something more 'solid', that is, I'm getting ready to work.

I shall go to Paris before returning to Russia; that will be towards the end of April. I shall stay a good ten days — we shall see each other often.

If you see Mme Sand, give her my regards. Greetings to Du Camp and the Husson family.

I embrace you and wish you courage! You are Flaubert after all.

Your I.T.

April 1870

I was very sorry to hear in your last letter that we shan't see each other this summer, my dear friend. I had counted on a good chance to let myself go with you, before your departure for Russia. But how difficult everything in this life is!

The great sadness I've had this winter has been the death of my closest friend after Bouilhet, a good lad called Jules Duplan who was devoted to me. These two deaths, coming one on top of the other, have overwhelmed me. Add to that the pitiful state of two other friends (not such close friends, it's true, but none the less they were part of my immediate circle). I'm referring to Feydeau's paralysis and the madness of Jules de Goncourt. The loss of Sainte-Beuve, money worries, my novel's lack of success etc., etc. even down to my manservant's rheumatism (the one who looks like Lassouche), everything, as you can see, has conspired to aggravate me. And to do so to no mean extent.

I can easily say that the only good thing to happen to me for a long time was your last visit, which was too short. Why do we live so far away from one another? You are (I think) the only man I enjoy talking to. I can't see that anybody else bothers about art and poetry! The plebiscite, socialism, the International and other such garbage are cluttering up everybody's brains.

I fear I shan't be able to accept your invitation this summer. Here's why. In four or five days' time I shall return to Croisset, where I'm going to write the preface to the volume of Bouilhet's verse straightaway. It will take me two or three months — after which, I shall tackle St Anthony which will be interrupted in October by the rehearsals for Aisse. They will rob me of a good two months. So between now and next New Year I shall have barely six weeks to devote to the good hermit. I would like to spend not more than two years on that fellow. So you see how pressed for time I am. I must get on with that work, as quickly as possible, as I'm already starting to feel I've had enough of it. I have consumed too many books, one on top of the other — but it was in order to make myself numb to my personal sorrows.

Send me your news when you're at home in Russia — and think of me often, because I often think of you, and I embrace you, ex imo

G. Flaubert

My mother was, as they say, very touched by your kind regards.