The Gift

by JOHN MONTAGUE

What really interested Brendan were my impressions of life on the Left Bank, which was then the intellectual capital of post-war Europe. The underground clubs like the Tabou, and the Rose Rouge, where Juliette Greco sang, the terraces of the ‘Maggots’ or the Mabillon were all well known to Brendan Behan. And they had already heard of him as a writer: Sinbad Vail, son of Peggy Guggenheim, had printed Brendan’s delicate story “After the Wake” in his magazine Points, though Brendan later repudiated it because it exposed his liking for boys.

In the exuberant bohemian atmosphere of Saint Germain, where Genet and Baldwin were leading lights, and Gide was the local Nobel laureate, no one cared a ‘fig’ about homosexuality. But back in melancholy Dublin, such sexual diversity was dangerous, and the naturally loquacious Brendan had to try to keep his mouth shut.

Brendan’s sexuality was complex and seldom fulfilled. He liked women but his early years in prison had given him a feeling for the fine manly forms of his fellow felons. He confided to me that what he would really like was ‘a boy on top of a girl, and myself on top of that,’ a pyramid not easily choreographed in the pious Ireland of our youth, or indeed, anywhere west of Bangkok.

Brendan Behan

Brendan Behan

When we re-met three years later, in 1954, we were both young married men, and by lucky chance, living more or less side-by-side, in Dublin’s genteel Herbert Street. It was noticeable that Brendan was migrating steadily from the North Side slums of his youth to the more sedate south, perhaps in a curve towards respectability?

Few people think of Behan as a husband, but that was the role in which I finally came to know him best. And my own wife took to him immediately, as she was meant to. When they first met, as Madeleine and I were walking by the misty Canal, he surprised her by asking if he could put his finger in her mouth.

”Bite, daughter,” he cried, “bite as hard as you can, on the knuckle.” A surprised Madeleine did as she was instructed, until Brendan’s face whitened.

”Jaysus, girl you’re a fine specimen, and may you have many children. But,” he continued, his eyes narrowing with mischief, "do you know what you’ve gone and done? You’ve married an Ulsterman. A grand girl like yourself, you’d expect a bit of appreciation and affection. But all you’ll get from one of that lot is a pair of cold feet in the bed.”

Madeleine Montague, John's first wife

Madeleine Montague, John's first wife

Then he launched into a fluent stream of street French, which delighted her exile’s heart; she found his command of argot unusual and impressive.

Brendan was now at the height of his powers, a formidable little bull crackling with energy and affection for the world. A trip to the Markets for an early morning cure, home to heavy breakfast, a few hours hammering at his antediluvian typewriter: that was how he completed Borstal Boy and began The Hostage, plus a new novel that opened sensationally: “There was a party to celebrate Deirdre’s return from her abortion in Bristol.” If he spent the rest of the day in the pubs, it seemed a natural enough reward, and, if you caught him early enough, there would be a gas session.

We did not discuss writing much, but there was a mutual respect despite the disparity in our achievements; Brendan’s fame was now worldwide, and I was only getting back to real writing after three years of wandering and teaching in the States. If I published a poem or review, he usually found something decent to say about it, although he still smarted from what he regarded as the unfair treatment he received. Dubliners like Iremonger, Jimmy Plunkett and even John Jordan he always spoke well of, but beyond the lingua franca of Dublin men and oppressed and besieged by culchies, there was his simple belief that writing was something sacred. He might joke about it, as he did about everything else, but it was what mattered. “You may roll in the gutter, as long as you don’t destroy the gift.” It seemed to me a very romantic attitude but later I came to regard it as almost a prophetic summary of his descent into the toils of self-destruction.

During these early years of marriage, Brendan tried his best to harness his demons. He was very proud of Beatrice and her extraordinary capacity, at least at the beginning, for quiet amusement at his antics, even when they were sometimes excessive. There is a lovely picture of him crushing his great animal head against her pale face, and his imitation of her, brush in hand before her easel, was one of his new party tricks. If the daughter had arrived earlier, I am convinced that Brendan would have lived, because he loved children as much as or more than he desired young men. I have a favourite image of him festooned with children at Blackrock Baths, performing elaborate belly flops for delight. And whenever Madeleine’s pretty little niece came to stay with us, Brendan would fire bags of bon-bons through the window, ‘pour la petite.’

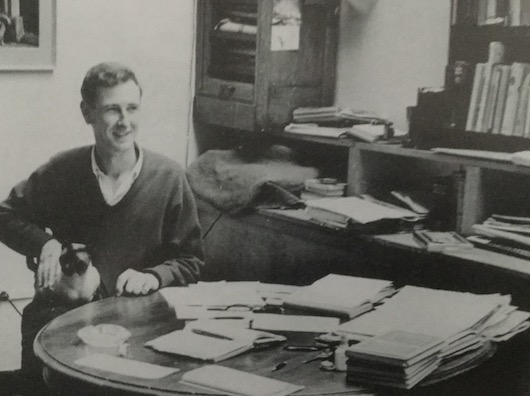

Montague, center

Montague, center

By eerie coincidence, my first marriage was also childless, and I recall a sadly hilarious exchange with Brendan cross-examining the novelist Benedict Kiely, in genuine puzzlement, as to how he had managed to have so many children, while Ben mumbled some vague consolation. It was as if he truly believed that he might be doing something wrong in the love department. For, despite the casual exchanges that sometimes prevailed in Dublin’s bohemia, we actually knew very little about sex in those days. And almost certainly nothing about problems like infertility, which even doctors discussed in hushed tones.

In my experience, in a childless marriage there is a tendency to revert to former habits, because the anchor that children provide is missing.

What aspects of his ‘peculiarly complicated personality’ brought about his downfall? There was his sexual ambiguity, for Brendan was, to use a Dublinism, a ‘bicycle’, or bisexual, pedalling forlornly with both feet. Most of his younger male contemporaries endured the occasional pass from Brendan, if he took a shine to you. But the advance usually so shy and stumbling as to be easily brushed off: the publicity-hungry Behan, who sought the crowd’s applause, was also deeply vulnerable. At the height of his fame, when he was staying in a West End London hotel, he took a fancy to a telegraph boy, who was bringing him messages of congratulation. Brendan was afraid to lay a hand on him, but liked him so much that he began to send telegrams to himself, just in order to see the boy and exchange a few pleasantries.

For all his impulses in that direction, Brendan seemed reluctant to pass through the mirror, to use Cocteau’s image. For, after all, one does not love in a vacuum, and declaring his homosexuality would have entailed a whole change of lifestyle that Brendan ultimately shied from. Or perhaps his real torture was that he was more or less equally attracted to both sexes, an ambivalence which might have been an albatross.

The above is excerpted from John Montague's memoir Company: A Chosen Life, which was published in 2001. Montague passed away in December in Nice at the age of 87.