Tunnelling

by JAMAL MALIK

Quantum theory and general relativity are increasingly finding skirmishes across science, with physicists hoping to finally resolve their incompatibilities. A simple way to describe their conflict is one of scale. It can be hard to shrink down the properties of gravity, a relativistic theory, to the purview of small things; the corollary, extrapolating quantum rules to macroscopic phenomena, is also messy.

A patchwork fix was proposed decades ago: string theory. If it helps make sense of it all, maybe there are eleven dimensions, or 26 or ten, and they bend around on themselves. I like this idea because it's ambitious and bizarre and hasn't actually, to date, reconciled anything.

+

Some events, like immigrating to the so-called first world, seem to be so profound and improbable that it might as well be crossing over from one universe to another. At age 30, my father left Bangladesh for the U.S., seeking asylum; although I know it happened, it still vexes me.

When you cross an ocean, how can you tell if you've made it completely?

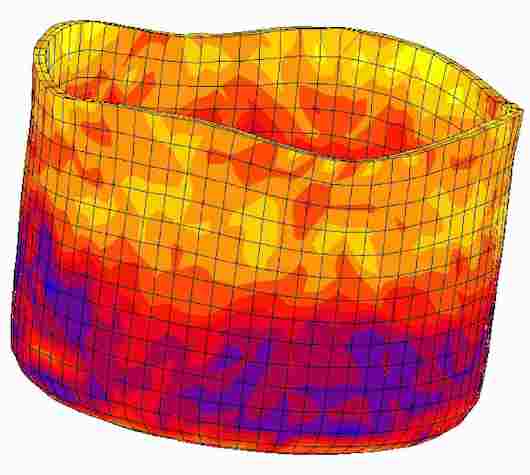

Physical space is often regarded as infinitely divisible: it is thought that any region in space, no matter how small, could be further split. Time is similarly considered as infinitely divisible.

However, the pioneering work of Max Planck (1858–1947) in the field of quantum physics suggests that there is, in fact, a minimum distance (now called the Planck length) and therefore a minimum time interval (known as the Planck time) smaller than which meaningful measurement is impossible.

Even if you split a mortgage, marry a white woman, and speak fluently in a new tongue, by all appearances looking assimilated from the outside, you likely know that there remains some distance unbridged, ineffable.

+

I moved from DC to Berlin this year to study carbohydrates at the Max Planck Institute. In tenth grade I believed chemistry to be a lingua franca. Now, in the 23rd grade, simple questions can return dizzying answers.

My father sent an insane e-mail and is maybe moving back to Bangladesh because my sister and I didn't become the Muslim adults he expected. But is there anything more speculative or experimental than having a child, much less with someone from another continent?

+

A month ago I fell down near Kottbusser Tor and I think I tore my meniscus. I want to talk to God so I was sober all Lent as a cover letter. I am also not religious but I wonder if He cares.

I think I owe, cosmically — it's an intuition, like the feeling of being watched. I’ve coasted for too long thinking I am mostly a decent person, and that is not enough in a world that trends towards hell.

Other debts: a long letter requiring a precise amount of contrition, several thank-you notes, 33000 USD, polite wedding declines, a DC Public Library fee.

String theory etiquette: if you have a dream about someone you can tell them or fuck them but not both.

If you find your friend’s doppelgänger at Hermannplatz, it’s okay to hit them with a tire iron. If you text your ex from a German number, you have to expect nothing in return. It is essentially a message in a bottle.

+

Half third-world, half second-generation. Only Americans call the children of immigrants "second-generation," elsewhere it’s first. Now that I am elsewhere, I am everything from a 2.5 to a 1.5 to a one (my friend says these things are up to me.)

We’ve killed the coral reefs and the ice caps are on the way out. In Arrival I thought the aliens had more faith in us than I do. In Interstellar we went through a wormhole to find a new planet and I wasted three hours.

+

I have always felt like somehow my life was out of sync. I assume living your life commensurate with time feels like walking smoothly, you don’t even notice it at all.

I used to think my asynchronicity was because I skipped first grade. But maybe the hubris or fear involved in crossing an ocean, from this generation or a previous one, comes with a penalty. Maybe I'm off by a Planck time and a Planck length, a debt to an uncertain and unknowing collector.

+

If we are in one of many possible universes, it feels cruel to be so limited in accessing them. In crisis we always wish to break the rules: I want to go back to this time, I want to be in that place.

We like the corollary in our high points: There is one path governed by fate. I was meant to meet this person, or to have that experience.

One measure of maturity is your ability to invert these instincts. Having the faith — it feels like a leap — to resist escapism during the lows, accepting that bad things can be done by or to you; and the humility to be grateful in happiness, knowing that it very possibly may not have met you.

+

Still, we can make choices, the venue by which we can slip from one universe into the multitudes. These possibilities, of course, seem tied to youth, and watching them disappear can be darkly mesmerizing.

Avoiding one-ways is limiting in itself, and after a certain point evading permanent choices is a somewhat petulant attempt to resist time.

It took until my late twenties to realize that not making a decision is, ironically enough, totally still a decision, and often the worst one.

Jamal Malik is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is a writer living in Berlin. He last wrote in these pages about reasons to run. You can find his twitter here.