BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Inherited Our Proclivity For Sex

Friday, October 9, 2009 at 9:00AM

Friday, October 9, 2009 at 9:00AM

Clever Girl

by MOLLY YOUNG

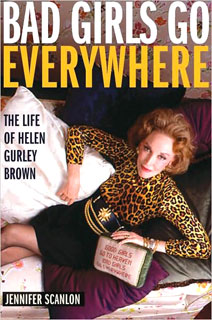

Bad Girls Go Everywhere: The Life of Helen Gurley Brown

288 pages, Oxford UP, $27.95

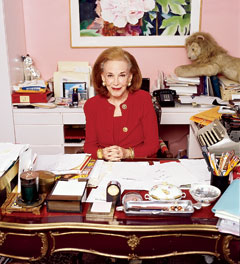

What a photograph! Here is Helen Gurley Brown on the cover of Jennifer Scanlon's new biography, resplendent in gold jewelry, cheetah print and a painted half-smile:

It is easy to be fooled by the atmospherics of Bad Girls Go Everywhere: The Life of Helen Gurley Brown, which has the look of a pulpy supermarket biography but is written by a professor of gender studies at Bowdoin and published by Oxford University Press. It is the hardcover equivalent of Alexander McQueen for Target — a high-low mix of intriguing proportions and dubious viability. Does it succeed? Yes and no.

We'll begin with an overview of the subject's life.

Helen Gurley Brown, best known as the editor of Cosmopolitan, was born in 1922 in Green Forest, Arkansas to a glum, resentful mother and a father who died while his daughter was young. Following the death of her father, the family moved to California to seek medical treatment for Helen's sister Cleo, who was crippled by polio. A self-described "mouseburger" with "wall-to-wall acne," Helen realized early on that she could surpass her poverty and hillbilly status only with thunderous charm and hard work.

People have been telling me I look good in a bikini for nineteen years. I wore my first one at age two.For years Helen supported her family with a succession of secretarial positions (seventeen to be precise), enjoying affairs with her higher-ups along the way and refining her seductive wiles with great determination.

People have been telling me I look good in a bikini for nineteen years. I wore my first one at age two.For years Helen supported her family with a succession of secretarial positions (seventeen to be precise), enjoying affairs with her higher-ups along the way and refining her seductive wiles with great determination.

The first breakthrough came in 1956, when Helen was finally able to write copy for the ad agency where her former position involved typing receipts. Her accounts included Catalina swimsuits and clothing, Sunkist, Breast O' Chicken and Pan-Cake cosmetics, for whom she wrote:

Tonight you must be more beautiful than you really are...you must be beautiful, period, when your mirror has been telling you for years the most extravagant adjective that can ever apply to you is...attractive. Poof to that! Tonight you will be beautiful!

Helen Gurley quickly became the highest-paid female copywriter on the West Coast. Cleo and Helen's mother subsequently moved out in order to provide their breadwinner with a measure of freedom and to seek polio treatment for Cleo elsewhere. Helen used her new freedom to style herself as a glamorous (and crafty) girl-about-town. She became adept at scheming in and out of the office, cajoling dates into paying for her cocktails and restaurant tabs while pinching pennies by ordering the cheapest item on the menu at company-funded lunches and spending the remainder on stockings. When her boss requested that she purchase a thermometer for the office, Brown scrounged around until she found one, then submitted a receipt for a pint of gin to share with her girlfriends that night. Clever girl.

"If you're not a sex object, you're in trouble."Self-effacing and incredibly industrious, Helen never denied that the charming, coiffed version of herself was a creation. This, in fact, would later become her platform: if she could make the glamorous switch from "mouseburger to career-woman status", then anyone could. Helen's sexiness is much discussed by Scanlon and by those interviewed in the book, who attempt to describe what it consisted of (since beauty and good breeding were not Helen's birthrights).

"If you're not a sex object, you're in trouble."Self-effacing and incredibly industrious, Helen never denied that the charming, coiffed version of herself was a creation. This, in fact, would later become her platform: if she could make the glamorous switch from "mouseburger to career-woman status", then anyone could. Helen's sexiness is much discussed by Scanlon and by those interviewed in the book, who attempt to describe what it consisted of (since beauty and good breeding were not Helen's birthrights).

The answer, of course, is that Helen Gurley's sexiness was made of wit, an unconcealed sexual appetite, coquetry and scrupulous grooming. She insisted (and continues to insist) that her natural gifts are nothing special; that her charm is learned and her sexiness self-taught.

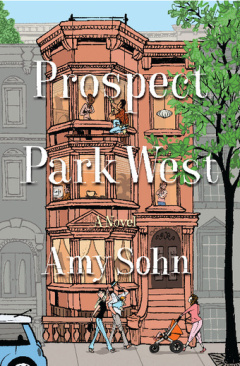

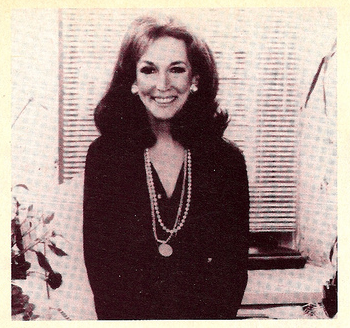

A taste of what's to come.Even at a young age Helen knew the value of a flashy gesture. With the cash saved up from her secretarial positions she bought a 190 Mercedes Benz sports car and zoomed around Los Angeles in it, strategically adding a sports car to her quiver of attractions. She continued writing ad copy and remained happily single until age 37, when she became engaged to David Brown, a wealthy businessman who admired Helen's achievements and work ethic. "I had gone through boys like popcorn," she later recalled. "I was ready to be true." The two were married in 1959 in a quiet Beverly Hills ceremony followed by dinner and a performance by the stripper Candy Barr.

A taste of what's to come.Even at a young age Helen knew the value of a flashy gesture. With the cash saved up from her secretarial positions she bought a 190 Mercedes Benz sports car and zoomed around Los Angeles in it, strategically adding a sports car to her quiver of attractions. She continued writing ad copy and remained happily single until age 37, when she became engaged to David Brown, a wealthy businessman who admired Helen's achievements and work ethic. "I had gone through boys like popcorn," she later recalled. "I was ready to be true." The two were married in 1959 in a quiet Beverly Hills ceremony followed by dinner and a performance by the stripper Candy Barr.

Although Helen credited her long period of singlehood with molding her into a sparkling, voracious woman, she was not a common specimen. A collection of essays in 1949 titled Why Are You Single? treated unmarried women as delinquents, and by 1951, one in three women were married by age eighteen. It wasn't until the birth control pill hit the market in 1960 that a young woman's sexual horizon widened, and with Helen Gurley Brown's splashy first book — 1962's Sex and the Single Girl — the public was sufficiently receptive to snap up more than two million copies in three weeks.

Sex and the Single Girl, which was given its title by David Brown, was initially a hard sell. Publishers shied away from the project, citing the book's racy content as a liability. Though written during Helen's marriage, the book chronicled the glitzy single life she invented for herself and was intended to pave the way for other like-situated girls. After reading the manuscript, Helen's mother wrote to her daughter that "it may be a sensation and get a great deal of publicity, [but] so do murder and rape!"

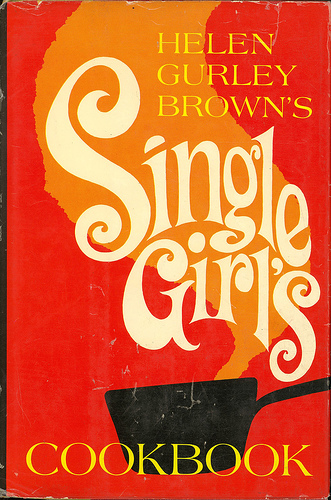

Smart women like to sex it up.Revisiting the little volume now, it is easy to recognize Brown's direct, casual style as the precursor of everything from Sassy and Jane to Candace Bushnell and Secret Diary of a Call Girl. "You inherited your proclivity for [sex]," she wrote to her audience. "It isn't some random piece of mischief you dreamed up because you're a bad, wicked girl."

Smart women like to sex it up.Revisiting the little volume now, it is easy to recognize Brown's direct, casual style as the precursor of everything from Sassy and Jane to Candace Bushnell and Secret Diary of a Call Girl. "You inherited your proclivity for [sex]," she wrote to her audience. "It isn't some random piece of mischief you dreamed up because you're a bad, wicked girl."

While Brown described the book as a gushy, bubbly slip of a thing, the author of Bad Girls Go Everywhere gives it serious consideration, offering that "Sex and the Single Girl, like Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique, introduced feminist thinking to millions of readers, documented both women's aspirations and discontents, and refused to apologize for its bold demands for women."

Brown quickly became the black sheep of the second-wave feminist movement. She adored a free-market economy where others critiqued it for encouraging male supremacy, viewed men and women as "equally competent but also equally bloodthirsty," and believed women ought to be drafted into the military. Exchanging sexual favors for gifts and dinner dates was fine by Helen at a time when some radical feminists were theorizing marriage as a form of prostitution. She shrugged this off. "In a way, we're all prostitutes."

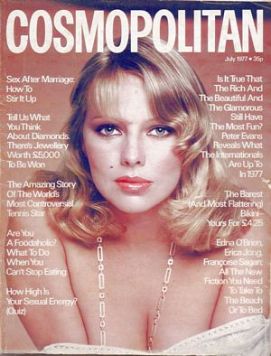

"As someone who worked her way up from secretary to copywriter to popular writer to magazine editor, Brown believed not in overthrowing the system but, rather, in working it," Scanlon notes, adding that Brown's philosophy of feminism was one "compatible with both capitalism and popular culture". Brown chafed at Gloria Steinem's insinuations that she was a victim, and while she agreed that femininity was a performance, she disagreed that the performance was malignant or insincere. Dressing sexy and wearing makeup was fun for all women, she argued. Even lesbians. Step Into My ParlorIn March 1965 Brown took over Cosmopolitan with no magazine or editorial experience. Most people assume the magazine started with her, but at the time of the takeover it was an eighty-year-old Hearst publication with a dusty history and a declining readership, filled mostly with domestic tips and world news. Brown's first issue put a chesty blond on the front cover and blurbed a story about birth control a few inches away from the model's cleavage. Sales of the inaugural issue shot up by a quarter million copies.

Step Into My ParlorIn March 1965 Brown took over Cosmopolitan with no magazine or editorial experience. Most people assume the magazine started with her, but at the time of the takeover it was an eighty-year-old Hearst publication with a dusty history and a declining readership, filled mostly with domestic tips and world news. Brown's first issue put a chesty blond on the front cover and blurbed a story about birth control a few inches away from the model's cleavage. Sales of the inaugural issue shot up by a quarter million copies.

However purposefully she might have swished through the office halls in Midtown Manhattan, Helen Gurley Brown was still a "lady editor". Her name was not on the invite list to company parties, and the male managing editor of Cosmopolitan openly dismissed her as unrefined and unfit for the job. The night after her first day at work, Brown's husband woke in the night to find his wife huddled in catatonic shock beneath her home desk.  To counter the stress of penetrating a hostile environment, the two decided to form an alliance. David began to pick up his wife every afternoon at work for a quick drive around the city and a hashing-out of the day's challenges, after which David would drop her back off at the office. She quickly gained her stride and shed the insecurities of running a huge operation. Sales climbed, Francesco Scavullo shot the magazine's covers and everyone from Joyce Carol Oates to Danielle Steel contributed stories. Helen was known to be a good boss with a loyal base of employees, and the magazine's circulation grew.

To counter the stress of penetrating a hostile environment, the two decided to form an alliance. David began to pick up his wife every afternoon at work for a quick drive around the city and a hashing-out of the day's challenges, after which David would drop her back off at the office. She quickly gained her stride and shed the insecurities of running a huge operation. Sales climbed, Francesco Scavullo shot the magazine's covers and everyone from Joyce Carol Oates to Danielle Steel contributed stories. Helen was known to be a good boss with a loyal base of employees, and the magazine's circulation grew.

One typical Helen habit that never quite dissipated, as many employees later noted, was her stinginess. The editor was particularly known for packing a brown-bag lunch every day (tuna salad in an old yogurt container) and regifting freely. One girl opened a box of chocolates to find that the truffles were imprinted with Helen's initials. Brown continued to bring her lunch to work until age 86.

Another classic Helen trait was her reed-thin frame. She made no bones about the effort required to maintain her figure, noting that she occasionally threw a glass of champagne into the house plants at parties to avoid drinking it. "I love food like a normal person," she said, "But I love being skinny more." Adhering to a permanent diet, she weighed herself daily and exercised ninety minutes per day, missing her regimen only twice in twenty years. Although she took pride in preparing breakfast and dinner for her husband, she often refrained from eating with him. "I think we should come down hard on the creeps and bullies but not go stamping out sexual chemistry at work."Betty Friedan dismissed Cosmopolitan as a "horrible monthly" demonstrating "nothing but contempt for women." What she perceived as the snobby undertones of feminist critiques outraged Brown, who fired back that only the most privileged women could renounce the feminine dress, manners and makeup required by many female occupations. Most women working as secretaries, receptionists, nurses and flight attendants had to look and act a certain way to remain employed. "One thing I do well," she said, "is deal with reality."

"I think we should come down hard on the creeps and bullies but not go stamping out sexual chemistry at work."Betty Friedan dismissed Cosmopolitan as a "horrible monthly" demonstrating "nothing but contempt for women." What she perceived as the snobby undertones of feminist critiques outraged Brown, who fired back that only the most privileged women could renounce the feminine dress, manners and makeup required by many female occupations. Most women working as secretaries, receptionists, nurses and flight attendants had to look and act a certain way to remain employed. "One thing I do well," she said, "is deal with reality."

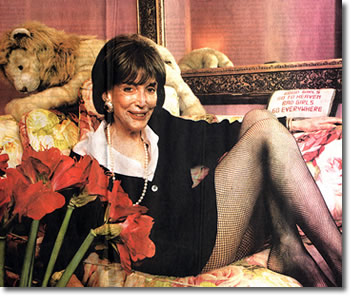

A defender of miniskirts and plastic surgery, Brown employed both in her personal mission to remain vital in her later years. "Older age is just the pits," she said, "but you have to be some kind of nutcase to assume you're escaping it. So I escape it the best I can, through my work."

Although Cosmopolitan began to decline in the 1980s, Brown held on to her position until she was forced out in 1996 and replaced with Bonnie Fuller. Fuller stuck to the old formula — which seemed to work — before leaving for Glamour and being replaced by Redbook's Kate White. The magazine remained more or less the same and continues to sell briskly, though not as well as it used to. There are now sixty editions of Cosmopolitan published in thirty-six languages and distributed in more than a hundred countries. "We owe the 'battle axes' of another era more than we can ever pay. They had to be hard as nails and drive themselves in like nails to compete with men. Not you, magnolia blossom!"What can I say about Scanlon's biography? Helen Gurley Brown is enchanting. I did not exactly find myself nodding along with the author's arguments for Ms. Brown as a feminist hero, but the claims are not absurd. Scanlon is a dedicated researcher (there are many footnotes) and a brisk writer. She digs up facts, provides connective tissue, extrapolates plausibly and makes leaps that a reader is free to agree with or shrug away. In other words, she is a competent biographer.

"We owe the 'battle axes' of another era more than we can ever pay. They had to be hard as nails and drive themselves in like nails to compete with men. Not you, magnolia blossom!"What can I say about Scanlon's biography? Helen Gurley Brown is enchanting. I did not exactly find myself nodding along with the author's arguments for Ms. Brown as a feminist hero, but the claims are not absurd. Scanlon is a dedicated researcher (there are many footnotes) and a brisk writer. She digs up facts, provides connective tissue, extrapolates plausibly and makes leaps that a reader is free to agree with or shrug away. In other words, she is a competent biographer.

A review by Charlotte Hays in The Wall Street Journal snipes that "The book's photos often capture Helen Gurley Brown more vividly than Ms. Scanlon's less-than-vivid prose. In my favorite shot, Ms. Brown is rail-thin at 68 and dancing with John Mack Carter, then the president of Hearst Magazines. She is wearing a mini-skirt, her face is hard and her smile frozen. Is she happy? Who knows. Is she a feminist hero? Who cares."

This is a silly critique. Ms. Brown's smile is frozen because it's a photograph. She looks great in a miniskirt and appears to be an enthusiastic dancer. None of these things, including Hays' evaluation of Brown's happiness, has to do with the latter's achievements. And the proposition that Brown is a feminist icon, while debatable, is no doubt worthy of discussion.

Molly Young is the contributing editor to This Recording. She blogs here and here, for Spike Jonze's new movie. She twitters here. You can buy her books here. She is creator of Salad & Candy. She last wrote in these pages about a seminal moment from her youth.