Our New York series continues with Nancy Jo Sales' classic Vanity Fair piece about Theresa Duncan and Jeremy Blake.

The Golden Suicides

by Nancy Jo Sales

On a rainy October night in Washington, D.C., the friends and family of Jeremy Blake gathered for a private memorial service at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Blake, an art-world star acclaimed for his lush and moody “moving paintings,” shape-shifting innovations mixing abstract painting and digital film, had ended his life on the night of July 17, walking into the Atlantic Ocean off Rockaway Beach, Queens, never to return.

“I am going to join the lovely Theresa,” Blake, 35, had written on the back of a business card, which he left on the beach, along with his clothes. Police helicopters searched for him for days on the chance he might still be alive. Friends prayed that he was, talking of how his passport was missing, he had bought a ticket to Germany. Then on July 22, a fisherman found his body floating 4.5 miles off Sea Girt, New Jersey.

“The lovely Theresa” was Theresa Duncan, a writer, filmmaker, computer-game creator, and Blake’s girlfriend of 12 years.

He had found her lifeless body on July 10, in the rectory of St. Mark’s Church in Manhattan’s East Village, where the couple had been renting an apartment. There was a bowl full of Benadryl pills, a bottle of Tylenol PM, and a champagne glass on the nightstand. There was a note saying, “I love all of you.” Duncan was 40.

The last post on her blog, “The Wit of the Staircase,” was a quote from author Reynolds Price about the human need for storytelling and the impossibility of surviving in silence.

No one who spoke at Blake’s memorial service that evening at the Corcoran said anything about Theresa Duncan. Almost no one mentioned her name. (It happened to be her birthday, October 26.) No one talked about the dark stories and wild speculation that had emerged after news of the couple’s “double suicide” hit the media. There had been reports they had become “paranoid,” obsessed with conspiracy theories, believing they were being harassed by Scientologists.The Internet filled up with conjecture about government plots and murder. Something about their story seemed to capture the modern imagination, if only because no one knew exactly why two such accomplished and attractive people had chosen to make their exit.

Nancy Jo Sales archive at New York Magazine

“In the summer of 2006, I saw my brother for the first time in years,” said Blake’s 18-year-old sister, Adrienne, crying, “and I could tell he was completely different from what he had been. It frightened me.”

In their final days in New York, Blake and Duncan would seek refuge from the demons they believed were chasing them in the company of a radical Episcopalian priest, Frank Morales. Morales became one of their closest friends and confidants. He is also my ex-husband. We were married in 2004 and separated in 2006, a few months before he met the couple. The day after Jeremy Blake disappeared, Frank showed up at my door. He was visibly upset and said he wanted to talk. “What about?,” I asked. I hadn’t seen him in months. He started to tell me the story. “He slipped through our fingers,” Frank said of Blake.

blake

In a letter dated August 9, 2006, Blake and Duncan’s landlord in Venice, California, Sabrina Schiller, informed them that they had to move out. The neighbors on either side of their quaint Craftsman bungalow had told her, Schiller said, that they were “determined to seek police protection if necessary.”

A statement in support of their eviction was taken from one of the neighbors, Katharine O’Brien, 25, then the girlfriend of indie movie producer Brad Schlei. Earlier in the year, Schlei, a collector of Blake’s work, had hired him to direct an adaptation of the George Pelecanos novel Nick’s Trip.

“On the evening of May 9, 2006,” said O’Brien’s statement, “Theresa approached my bungalow and rapped on the window. Upon opening the door I was immediately greeted with the following questions… Theresa said to me, ‘Jeremy and I have started a club where we’ve found a bunch of old men and we’re letting them fuck us in the ass, and we wanted to know if you wanted to be a part of it.’ I asked Theresa if she was joking. She said ‘no’ and repeated herself. I asked if she was trying to imply something about the age difference between my boyfriend and me.” (Schlei is 41.) “She said ‘no,’ smiled, and walked away.

“That night”—a night Blake seemed to be away, uncharacteristically leaving Duncan alone—“Theresa … returned to my bungalow five or six times,” the statement continued. “Out of the blue, she asked if I was a Scientologist.… For the record, I have no connection whatsoever with Scientology, and have never been a Scientologist.”

In the months prior to this encounter, the two couples—Duncan and Blake and O’Brien and Schlei—had become friendly with each other. Schlei had even signed the “loyalty oath” Blake and Duncan had taken to asking of some friends. “I just want to get this film made,” Schlei told someone.

“Theresa was acting very strangely,” O’Brien’s statement said. “She was displaying jerking body movements; her face and hands were twitching. She continued to accuse me of being a Scientologist and part of a Scientology conspiracy to defame her.… At times I would hear her cackling and hooting from the alley.

“The next day, May 11, [Blake] withdrew from the business relationship he had with my boyfriend, claiming that I was a Scientologist and that my masters in Santa Barbara (my parents’ home) were instructing me to defame Theresa.”

Schlei says that Blake later told him he could provide him with “proof” that O’Brien was a Scientologist, but he never did. In July, when O’Brien came home and picked up her mail, she wrote, Duncan “shrieked ‘cult whore’ and ‘cult hooker’ repeatedly. She was very frightening.”

In 2002, the year she and Jeremy Blake moved to Los Angeles (they had been living in New York since 1995), Duncan was riding the crest of a seven-year wave of success. Stories about “Silicon Alley’s dream girl” had appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, People, along with dozens of photographs of her looking glamorous. She had been to “new media” what Jane Pratt was to magazines or Tabitha Soren to MTV—the pretty girl, the chosen one. Her CD-roms, Chop Suey, Smarty, and Zero Zero, had been hailed as breakthrough games for girls. Chop Suey was named Entertainment Weekly’s “CD-rom of the Year” in 1995.

When she moved to Los Angeles, Duncan had a two-picture deal with Fox Searchlight and had written and directed a pilot for Oxygen Media. She had “my boyfriend Jeremy Blake”—she was always bringing him up—literally the poster boy of the 2001 “BitStreams” exhibition of digital art at the Whitney Museum. That same year, Blake had been tapped by director Paul Thomas Anderson to create a hallucinogenic dream sequence for Punch Drunk Love, and singer-songwriter Beck had asked him to do a series of covers and a video for his album Sea Change (both released in 2002).

And then, something began to go very wrong.

“Yes, it looks like New York is a good idea for a few,” Blake wrote breezily in an e-mail to a friend on December 22, 2006, announcing that he and Duncan were moving back. They had evacuated their Venice bungalow two weeks after receiving their landlord’s August letter, cramming themselves into the small office space near the beach Blake had been using as a studio. They were low on funds.

Blake wrote of how he and Duncan had been “harassed here to the point of absurdity” by people who were so “paranoid” that it made him “laugh.” He said that they had been “defamed by crazy Scientologists,” threatened and followed by “their thugs.” (The Church of Scientology has denied any knowledge of the couple.) He wrote of how New York was starting to seem like the place for them to be, a place where they could speak “freely” to “exceptional people” and get their projects started.

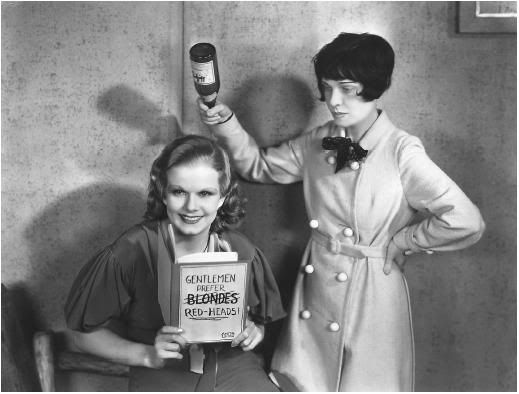

It was The History of Glamour—the witty, 40-minute-long animated film Duncan made while at Nicholson—that got her noticed by Hollywood. The film, a semi-autobiographical satire about the rise of an indie-girl rocker, showed in the 2000 Whitney Biennial—another milestone in Duncan’s own ascendance. (Glamour was co-illustrated by Jeremy Blake.) It’s hard, watching it now, to understand how Duncan ever wound up a suicide. Her movie is full of wry humor and silliness, and is a cautionary tale about the emptiness of fame and the corrupting influence of ambition.

The cosmic pileup was in overdrive when, in mid-January of 2007, Blake and Duncan moved into the St. Mark’s Church rectory and instantly befriended Father Frank Morales.

Morales, 58, is a longtime East Village activist, generally credited as being the leader of the New York squatter movement of the 80s and 90s. In the last 10 years, he has refashioned himself as a journalist, investigating what he refers to as “the domestic operations of the Pentagon” and the “militarization of the police.” He is the winner of two Project Censored awards (for “The News That Didn’t Make the News”) from Sonoma State University, most recently for his Internet-published piece “Bush Moves Toward Martial Law” (2006).

In short, he’s the radical left’s Fox Mulder, a man who makes mere “conspiracy theorists” look like Sunday drivers.

“My paranoia is rooted in reality,” he says, half joking.

When Blake and Duncan moved back to New York in early January of 2007, Duncan very much wanted to get the rectory apartment at St. Mark’s. It was both beautiful, overlooking the church’s garden, and bizarre, allegedly haunted by the ghosts of Edgar Allan Poe and Harry Houdini.

Morales, who saw them as the sort of people who belonged at the church—long a hangout for artists, from Andy Warhol to Allen Ginsberg—walked out of the meeting with them and assured them he would put in a good word. “Jeremy kind of looked at me sideways and said, ‘You’re a priest?’ And I looked back at him and said, ‘You’re an artist?’ We immediately liked each other,” he said.

Frank Morales

And yet, she seemed to fear that she was becoming unknown. One night, at a gathering of New York friends at the rectory apartment—she and Blake were once again throwing lively soirées—Duncan dragged out of a closet her old CD-roms and a copy of The History of Glamour. “Everybody kind of looked at each other like, Oh no, what is she doing?” said someone who was there.

Maybe it was Morales’s refreshing lack of knowledge of anything connected with Hollywood that made the couple gravitate so heavily now toward the hip pastor. Or maybe it was his knowledge of subjects which had come to interest them, which other friends of theirs considered a bit nutty. “The U.S. government invaded Iraq on the basis of lies and still some people want to deny the existence of conspiracies,” said Morales.

her death

Around seven p.m., Blake came home from work. Walking through the church garden he saw Morales and invited him up. Morales said he would join them in a few minutes.

Then, about 10 minutes later, Morales said, he noticed there were a number of police cars outside the rectory entrance on East 11th Street. He hurried up to the apartment, where Blake was in the living room, “sobbing, pounding the walls with his fist, screaming, ‘Dammit, fuck, no, this can’t be happening.’ ”

The police were with Duncan’s body in the bedroom. Blake never went back inside. He had found her on the bed. Her face seemed almost smiling. Somehow, one of her hands had traveled up toward her cheek and was frozen there, as if she had just thought of something else she wanted to say.

Some detectives arrived and began questioning Blake in Duncan’s office. Was she depressed? Was she stressed out? they asked him. “No more than usual,” Blake said, shaking his head. Did you have an argument? “No.”

Morales asked to be let into the bedroom to perform last rites over Duncan’s body. She was now on the floor, where the E.M.S. workers had been examining her. He knelt down and spoke the prayers. “It didn’t seem possible,” he said. “It seemed so out of character.”

For several hours, Blake had to wait for the morgue workers to come and take away her body. He wouldn’t leave Duncan’s office or go near the bedroom, continuing to sit motionless, “looking very withdrawn.” One cop stayed, standing watch in front of the bedroom door.

Finally, around 11 p.m., the men from the morgue arrived. (The official cause of Duncan’s death was suicide by acute intoxication due to the combined effects of diphenhydramine—which is present in Benadryl and Tylenol PM—and alcohol. The New York City medical examiner’s office would not comment on whether there were other drugs found in her system.)

Nancy Jo Sales' article on which movie is being made

his death

‘Dear All,” read the e-mail Blake sent to a few people, including his gallerist and curator, on the morning of July 12. He apologized for having to relay the news that he had “suffered a terrible and unexpected personal tragedy this week.” He then told everyone that Theresa had “passed away.”

Blake said that Theresa was “never a person to compromise,” and that he had a “clear understanding” that she had made the decision to end her life. He said that in doing so she had exhibited the same “strength” that she had shown when she was alive.

He asked his friends that they mention to everyone they spoke to of her death that she was “beautiful, generous, and lived by a code all her own,” that they not “spread more sadness in the world,” but “show respect” for someone who had loved them all.

And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate.

The blog post Duncan set for January 1st, 2008

And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate.So here I am, in the middle way, having had

twenty years -

Twenty years largely wasted, the years of

l'entre deux guerres -

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind

of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better

of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or

the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so

each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate,

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what

there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already

been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom

one cannot hope

To emulate - but there is no competition -

There is only the fight to recover

what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now,

under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither

gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not

our business.

--T. S. Eliot

East Coker

Four Quartets

"Rent a Cop" - Blitzen Trapper (mp3)

"New Shoes" - Blitzen Trapper (mp3)

"Fire & Fast Bullets" - Blitzen Trapper (mp3)

PREVIOUSLY ON THIS RECORDING

A series of essays exploring the history, architecture, art, film, music and culture of New York City.

Part One (Will Hubbard)

Part Two (Matt Lutton)

Part Three (Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Four (Molly Young)

Part Five (Alex Carnevale)

Part Six (Rachel B. Glaser)

Part Seven (Brittany Julious)

Part Seven (Andrew Zornoza)

Part Eight (Bridget Moloney)

CELEBS

CELEBS  Tuesday, March 17, 2009 at 11:41AM

Tuesday, March 17, 2009 at 11:41AM