In Which We Survive Appalling Experiences With Grace

Friday, February 13, 2009 at 11:50AM

Friday, February 13, 2009 at 11:50AM This is the latest entry in our series about writers of the American South. For past entries, look here.

On Tennessee Williams

by Karina Wolf

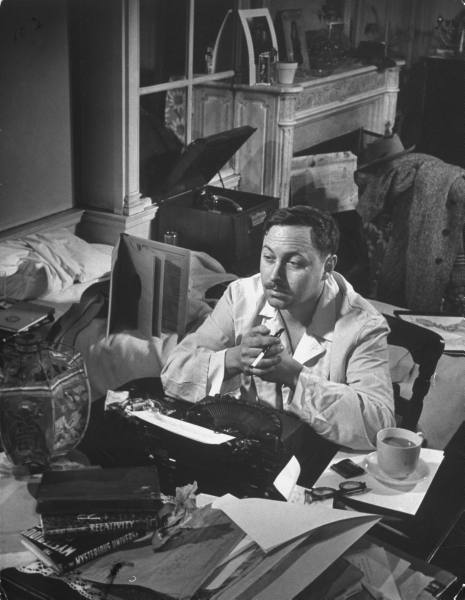

“High station in life is earned by the gallantry with which appalling experiences are survived with grace.” Tennessee Williams’ remarks at the death of his sister allude to the difficulty of living with mental illness -- his relationship with his schizophrenic sibling had been fraught.

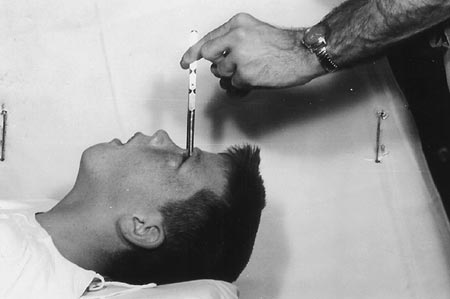

Rose was a perpetual source of concern, constraint, and provocation for the family, and while the playwright was in rehearsals for The Glass Menagerie, his parents allowed surgeons to lobotomize her. Psychosurgery has often been coercive at best, and the operation is medieval in its imprecision. The doctor severs the brain’s prefrontal lobe by inserting metal spikes through holes in the skull or through the eye sockets. The surgery left Rose permanently compromised and terminated her hopes for recovery.

Williams called Menagerie a memory play. Perhaps this designation was meant to excuse its elliptical narrative; certainly it alluded to the story’s biographical conflict, about a mother’s hope for her daughter’s return to normalcy and the sibling who acts as mediator. “It is sad and embarrassing and unattractive,” Williams admitted, “that those emotions that stir…are nearly all rooted…in the particular and sometimes peculiar concerns of the artist himself…a web of monstrous complexity…from the spider mouth of his own singular perceptions.”

For the Williams family, madness was an impenetrable cloister. The diplomacy of insanity demands anticipation, misdirection, suppression. A spouse or visitor can never comprehend the hidden hurts that bind, the minutely calibrated behaviors and the disappointed hopes in the family of the disturbed. Outside the tempest, one bears witness. It’s arguable that most writers create memory plays in one way or another; that Williams would name his form reflects how intimately these conflicts branded him.

*

I came late to Tennessee Williams. Maybe this is a function of the American paradox. To paraphrase a Yankee poet: we Americans contradict ourselves, we are a multitude. I hope the purpose of literature isn’t just to reify the importance of our own concerns, but the gentility of the South, its norms and mores and modes of expression seem utterly alien to this Northerner.

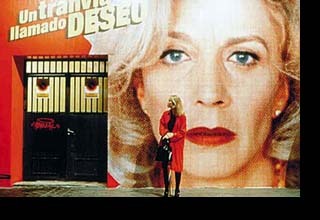

I recognized Williams, at last, in the works of contemporary film-makers: in the febrile moods of Wong Kar-Wai (an entire section of Blueberry Nights is lifted straight from Streetcar), in David Lynch’s pathological normality and expressionist experiments. When discussing All About My Mother, in which a character plays Blanche Dubois onscreen, Pedro Almodovar acknowledges a debt to Williams but insists that his character performs scenes from Streetcar as preparation to negotiate her own conflicts.

We can all learn from his conceit. The Spanish director dedicates his film to “women who act.” The idea, of course, is that "woman" and "performer" are exchangeable terms – and therefore the film is dedicated to more than biologically-mandated actors. Certainly, to be gay when Tennessee Williams was alive was to perform. And to be insane in the South of Tennessee Williams is a highwire act.

Despite the good breeding and the heavy drawl that earned him the handle “Tennessee,” Williams is not the most Southern of writers. He aspired to Southernness, and he came from a family with a society name (Lanier), but he was also gay, which left him at odds with the culture beyond his gothic family. (When queried about the provenance of her son’s toxic female characters, Williams mother regularly issued the disclaimer: “I have no idea where he comes up with them.”)

*

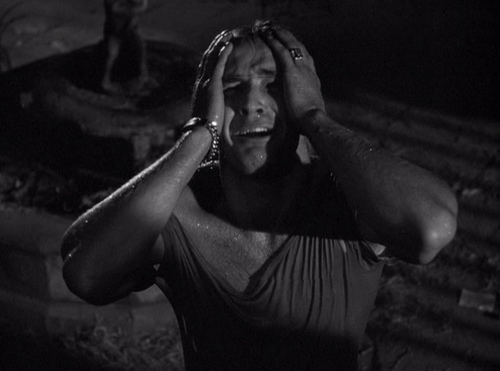

When you think of Tennessee Williams, what do you think of first? Marlon Brando’s tortured screams and the comfort from the woman he loves, when he shoves his brutish head against her belly. It’s hard to imagine a character of more inchoate passion than Marlon Brando’s Stanley Kowalski.

You have to understand Williams' cultural genealogy. He is the descendant of Artaud, Brecht and Cocteau. He was aiming for a theater of gesture; after all, when it works, writing is more of a sculptural than a logical art. “I think of writing as something more organic than words, something closer to being and action,” he wrote. Suddenly, Last Summer has nothing in common with contemporaneous dramas by Miller or Osborne – its roots are in European Expressionism and the Gothic romance of the Brontës. Williams’ emotional landscapes are elemental and volatile and poisonous. The Southern artifice is just a fractal outgrowth of the characters’ pathologies.

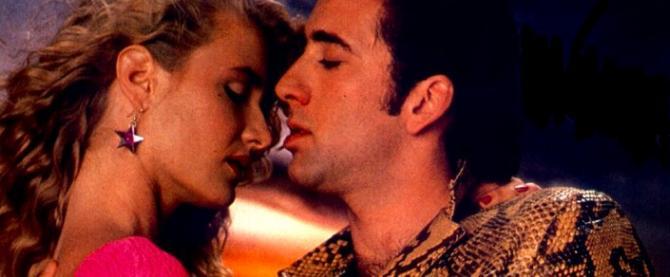

Williams’ success also coincided with the development of method acting, itself an exponent of rawness, not merely of naturalism. I find I can’t really talk about Williams without talking about film because that is how I was introduced to him – through the framings of Elia Kazan and Joseph Mankiewicz – and how I finally understood him – through his filmic imitators.

Even so, it took me a long time to understand the appeal of the plays. At a young age I could discern how Marlon Brando’s performance differed from the mannered banter of other actors. But he was repellent – it’s only later that you can see he’s appealing, how his coarseness is an antidote to the delusions of his wife and her sister.

In Suddenly, Last Summer I found my skeleton key. There are more famous and more revived works, but Suddenly, to me, is the yardstick by which all others can be measured. The play contains Williams’ archetypal characters: the fragile woman-girl “like a piece of her own glass collection, too exquisitely fragile to move from the shelf”; the arachnid mother; the depressive young man who must mediate an arena of monsters.

In the drama, brilliant and sensitive Dr. Cukrowicz is charged with eliciting funds from wealthy socialite Mrs. Venable in order to build a new psychosurgical hospital. The price of the new building is clear: Dr. Cukrowicz must perform a lobotomy on Mrs. Venable’s niece, who has been unmanageable since the death of Mrs. Venable’s son. Kathy, the niece, was witness to Sebastian’s violent and mysterious demise while the two were on vacation in Spain.

Before meeting the patient, Dr. Cukrowicz presses Mrs. Venable to specify her niece’s illness. The diagnosis is imprecise, but the affliction is universal: “Memory. She lacerates herself with memory.”

There’s that word again. Caught in memory, the self becomes two mirrors facing one another – an endless feedback loop in which the singular ego, or identity, gets lost. You start searching for yourself. As Kathy does, you start writing your diary in the third person.

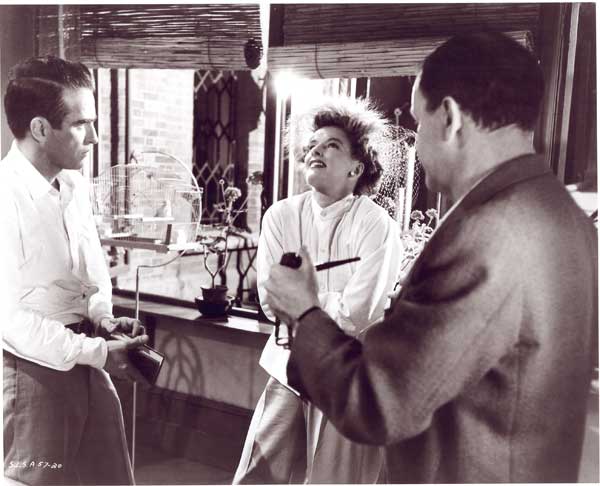

A bizarrely un-Southern triad of players enact the filmic version of Suddenly, Last Summer. Katharine Hepburn is the widow Venable, whose name seems to be a conflation of veniality and veneration. Her comportment is loathsome to her niece and subservient to her beloved son. Hepburn struts around in the headgear and outfits of an older version of her screwball character from Bringing Up Baby, but here the gaffes reveal deadly intentions.

Elizabeth Taylor has always been decadent; the instability we associate with her compensates for any thinness in performance. Her beauty is dated but manifest. She was made for perfume commercials or the affectless formalism of Last Year at Marienbad; she's perfect for the film, where the framing creates the drama as much as anything she says. Her power is not only her illness but in her knowledge. There’s something about Sebastian that Mrs. Venable wants to contain.

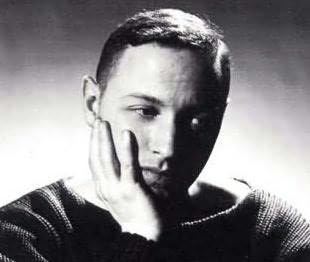

Montgomery Clift’s Dr. Cukrowicz has a welcome detachment. In essence, he’s allowed entry to the family secrets as he tries to determine whether to agree to perform the lobotomy. As he defers his decision, the surgeon develops an odd intimacy with his patient. He lights her cigarettes like a lover, allows her to wear high heels and Paris-bought fashions.

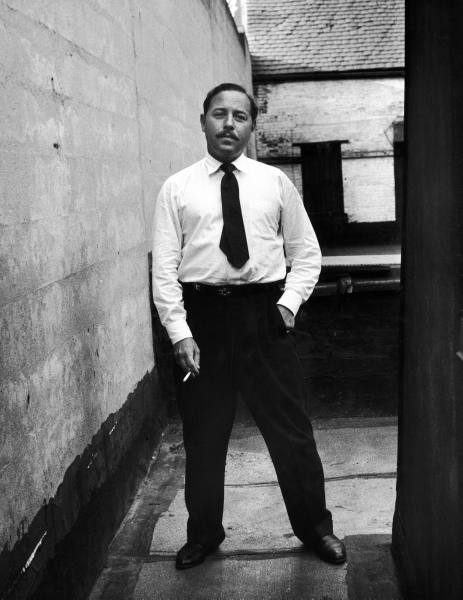

Clift, like Brando, was an actor of his moment. He embodied a new technique and carried a vulnerable, pansexual mien – a type of male so repellant to John Wayne that the star refused to socialize with Clift when they shot a film together. Clift was tortured by the sensitivities that can go hand in hand with addiction. He was further handicapped by changes to his appearance after a gruesome car accident. Marilyn Monroe once said of Clift that he was the "only person I know who’s in worse shape than I am.” Because the crew indulged his poor behavior, Hepburn reportedly spat in the face of the director at the end of filming.

It’s spot on casting, though, for a character who must serve as a Williams stand-in. As the ethical surgeon, he dithers, asking Mrs. Venable, "I can't guarantee that a lobotomy would stop her—babbling!!!" To which the aunt responds, "That may be, maybe not, but after the operation who would believe her, Doctor?"

Mental illness, particularly hysteria, has often been the affliction of women. Straight men may offer protection, comfort, diagnosis or salvation; but illness is a feminine domain. The pseudo-diagnosis of hysteria is similar to that vague term with which Kathy is classified, “dementia precox.” Even the doctor knows that this is a blanket categorization, empowering the doctor and belittling the diseased.

In many of Williams' plays, the arrival of a man offers hope and redemption – all thwarted by the hysterical behavior of the patient. There’s the sense that madness is consequent to a family imbalance that has no outlet. At best, the patient can achieve an awareness of the illness as it damages host and those around her. Think about Britney Spears’ helpless dissociation as she markets her bi-polarity versus the adult recognition of Sinead O’Connor, who talks with self-awareness about her disease, even as she periodically erupts into mad behaviors.

All this is to say: madness is viral. The lives of those surrounding the afflicted are irradiated by pathology. As in Grey Gardens, the illnesses must be symbiotic or the unit fails.

*

Something has failed in Williams’ Gothic spook sonata – a character has died and another must be silenced. So what is the need on the part of Mrs. Venable to hide from the strange facts about Sebastian? She can hardly speak the truth about him: his mother, and then his cousin, act as nurse/muse/procurer for the gay poet. As Kathy rightly says: “Sebastian wasn’t a man, he was a vocation.”

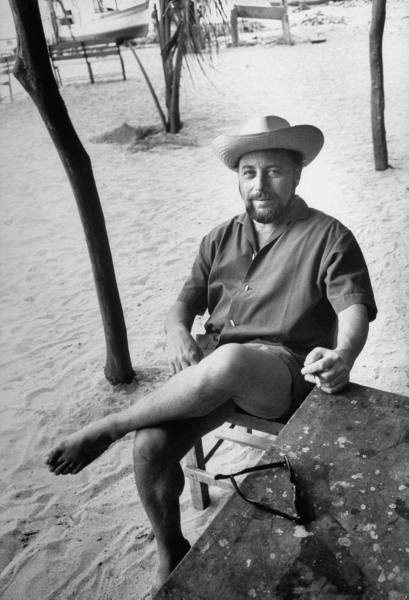

Like a good actor, Williams finds himself in his characters. Tennessee was prone to depression and limited by endless sensitivities. Certainly, his suffering must’ve inspired the troubled Doctor as well as the relationship between Kathy and Sebastian, which trespasses into Wuthering Heights’ incestuous taboos.

Williams’ first erotic experiences were closely linked to his sister: his concern for Rose transferred to the student pianist who arrived at the house regularly to practice with his sister. Williams writes: “For the first time, prematurely, I was aware of skin as an attraction. A thing that might be desirable to touch. This awareness entered my mind, my senses, like the sudden streak of flame that follows a comet. And my undoing... was now completed.”

A shocking ambivalence of thought and sensation tortured him, "Yes, Tom, you're a monster!" he told himself. "But that's how it is and there's nothing to be done about it. And so continued to feast my eyes on his beauty."

In Suddenly, Last Summer the self-loathing and the compulsion are both present. As much as Tennessee had to battle with his domineering mother and fragile sister, he himself was also damaged.

Mrs. Venable’s speech about Sebastian suggests something of Tennessee’s delicacy:

A poet’s vocation is something that rests on something as thin and fine as the web of a spider, Doctor. That’s all that holds him over!—out of destruction….Few, very few are able to do it alone! Great help is needed!

And then there are Williams’ letters. When his good friend Carson McCullers considered visiting him in Rome, Tennessee warned her: “You must remember all the bad things about me, my sensuality and license and neurotic moodiness at times – all the irregularities of my life and nature – I cannot put all those things into a letter! – and then ask yourself if you could really endure a close association or would I perhaps add to your worries and your emotional strains.”

Who is the greater monster in Suddenly, Last Summer? Mrs. Venable, who wishes to suppress the truth, or her son, who uses people to perverse ends? Williams imbues a toxicity to all. Kathy is fragile, but the entire family is mad. Ultimately, the doctor elicits the story of Sebastian’s behavior and violent death with a serum – as if the truth will solve the family’s pathology.

Truth, in fact, is Williams' second subject. In Streetcar, Blanche Dubois admits: “I don’t want realism. I want magic. I don’t tell the truth. I tell it as it ought to be….A line can be straight or a road. But the heart of a human being?” And here I find the greatness of Williams: truth and lies coexist – as do love, hatred, and indifference. Sane or mad, the human heart is troubled because it embraces contraries.

Karina Wolf is the senior contributor to This Recording. She lives in Manhattan, and she tumbles here.

"Siren Song" - Bat for Lashes (mp3)

"Daniel" - Bat for Lashes (mp3)

"Moon and Moon" - Bat for Lashes (mp3)

"Peace of Mind" - Bat for Lashes (mp3)

PREVIOUSLY ON THIS RECORDING

Molly Young enters the box.

Sarah just wasn't that into this movie.

Reader Comments (4)

fantastic piece

[...] In Which We Survive Appalling Experiences With Grace [...]

[...] Karina on Tennessee Williams [...]

[...] the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a [...]