Science Corner: The Happening Of The Triffids

by Molly Lambert

Plant Monsters are making a comeback in science-fiction, starring as the villains in The Ruins and The Happening. Cold war classic Invasion Of The Body Snatchers has plant monsters; alien seeds that drift to earth, take over human bodies and replace them with simulations grown from plantlike pods, perfect physical duplicates who kill and dispose of their human victims. It's all very timely in light of the new evidence of Panspermia causing controversy and excitement in the scientific world.

Also we might get to check out Martian Ice soon. Which reminds me of Howard Hawks's classic sci-fi film The Thing From Another World. Black and white fifties horror movies are the best. Something about there being no color adds an extra dimension of suspense and otherworldliness to what are already eerie stories. Although I'm glad Mad Men is in technicolor and not black and white, I'm surprised we haven't seen continuous B & W used as a TV style gimmick yet. It would be perfect for a Twilight Zone throwback horror serial, whether set in the past or not.

The Thing From Another World's Alien Antarctic Plants

I'm beyond excited at the idea that David Fincher might direct Charles Burns's graphic horror novel Black Hole, especially if he does it in Black & White, because I can imagine it reaching ungodly heights of beauty and terror. The scene in Zodiac with the couple on the dock (which really recalled seventies slasher flicks) was one of the film's best. My favorite comic right now that reminds me of Black Hole is Rick Altergott's Raisin Pie. It touches on similar themes of drugs, sex, and teenage dread.

A Frame From Charles Burns's Epic Black Hole

While Charles Burns draws in a darkly intense expressionist style, Rick Altergott is a masterful mimic of the masterful mimics of golden age MAD Magazine, guys like Will Elder, Harvey Kurtzman and Wally Wood. As with his previous strip Doofus (whose heroes recur in Raisin Pie), Altergott constructs rivetingly offbeat narratives while packing each frame full of details and jokes. I think he still lives in Providence with wifey Ariel Bourdeaux.

Art from Rick Altergott's Raisin Pie

I also love John Carpeter's (color) reinterpretation of Hawks's film, The Thing, which had some special effects by just passed on special effects god Stan Winston (R.I.P.). And I think real life plant monsters are fascinating, especially when they are underwater. So maybe we will find some underwater martian ice plant monsters. Most likely we won't find anything at all. Either way, it's pretty cool we've reached this point in the process of looking.

BACK TO THE PLANT MONSTERS:

"If the sea rocket detects unrelated plants growing in the ground with it, the plant aggressively sprouts nutrient-grabbing roots. But if it detects family, it politely restrains itself."

“Plants,” Dr. Dudley said, “have a secret social life.”

PLANTSTR: It's An Online Social Networking Site, For Plants

"The studies are part of an emerging picture of life among plants, one in which these organisms, long viewed as so much immobile, passive greenery, can be seen to sense all sorts of things about the plants around them and use that information to interact with them."

"Plants’ social life may have remained mysterious for so long because, as researchers have seen in studies of species like sagebrush, strawberries and thornapples, the ways plants sense can be quite different from the ways in which animals do."

a little parasitic Triffid growing on another plant

Some plants, for example, have been shown to sense potentially competing neighboring plants by subtle changes in light. That is because plants absorb and reflect particular wavelengths of sunlight, creating signature shifts that other plants can detect.

Scientists also find plants exhibiting ways to gather information on other plants from chemicals released into the soil and air. A parasitic weed, dodder, has been found to be particularly keen at sensing such chemicals.

Dodder is unable to grow its own roots or make its own sugars using photosynthesis, the process used by nearly all other plants. As a result, scientists knew that after sprouting from seed, the plant would fairly quickly need to begin growing on and into another plant to extract the nutrients needed to survive.

But even the scientists studying the plant were surprised at the speed and precision with which a dodder seedling could sense and hunt its victim. In time-lapse movies, scientists saw dodder sprouts moving in a circular fashion, in what they discovered was a sampling of the airborne chemicals released by nearby plants, a bit like a dog sniffing the air around a dinner buffet.

The title story Jizzle refers to a monkey in a circus side show

Then, using just the hint of the smells and without having touched another plant, the dodder grew toward its preferred victim. That is, the dodder reliably sensed and attacked the species of plant, from among the choices nearby, on which it would grow best.

“When you see the movies, you very much have this impression of it being like behavior, animal behavior,” said Dr. Consuelo M. De Moraes, a chemical ecologist at Pennsylvania State University who was on the team studying the plant. “It’s like a little worm moving toward this other plant.”

Although a view of plants as sensing organisms is beginning to emerge, scientists have been finding hints of such capabilities and interactions for 20 years. But discoveries have continued to surprise scientists, because of what some describe as an entrenched disbelief that plants, without benefit of eyes, ears, nose, mouth or brain, can and do all they are seen to do.

The problem, for many scientists, is that as obvious as the behaviors sometimes are, they can seem just too complex and animal-like for a plant. “Maybe if we understood more mechanistically how it’s happening,” Dr. Karban added, “we’d feel more comfortable about accepting the results that we’re finding.”

Plants are not “sensitive new age guys who cringe when something around them gets hurt and who love classical music and hate rock,” Dr. Dudley said as she referred to depictions in popular works of plants living tender, emotion-soaked existences, in particular the 1970s “The Secret Life of Plants”

Even mainstream researchers do not always completely agree on which ideas are clearly within the realm of science and which have gone a bit too far.

Recent debates have revolved around a longstanding question: which of the abilities and attributes that scientists have long considered the realm of just animals, like sensing, learning and memory, can sensibly be transferred to plants?

At the extreme of the equality movement, but still within mainstream science, are the members of the Society of Plant Neurobiology, a new group whose Web site describes it as broadly concerned with plant sensing.

The very name of the society is enough to upset many biologists. Neurobiology is the study of nervous systems — nerves, synapses and brains — that are known just in animals. That fact, for most scientists, makes the notion of plant neurobiology a combination of impossible, misleading and infuriating.

Authors from universities that included Yale and Oxford were exasperated enough to publish an article last year, “Plant Neurobiology: No Brain, No Gain?” in the journal Trends in Plant Science. The scientists chide the new society for discussing possibilities like plant neurons and synapses, urging that the researchers abandon such “superficial analogies and questionable extrapolations.”

Defenders point out that 100 years ago, some scientists were equally adamant that plant physiology did not exist. Today, that idea is so obviously antiquated that it could elicit a good chuckle from the many scientists in that field.

Blooooop! Itsa Me, Plant Monstorio!

As for the “superficial analogies,” the new wave botanists are well aware that plants do not have exact copies of animal nervous systems. “No one proposes that we literally look for a walnut-shaped little brain in the root or shoot tip,” five authors wrote in defense of the new group.

Instead, the researchers say, they are asking that scientists be open to the possibility that plants may have their own system, perhaps analogous to an animal’s nervous system, to transfer information around the body.

“Plants do send electrical signals from one part of the plant to another,” said Dr. Eric D. Brenner, a botanist at the New York Botanical Garden and a member of the Society of Plant Neurobiology.

Although those signals have been known for 100 years, scientists have no idea what plants do with them.

“No one’s asked how all that information is integrated in a plant, partly because we’ve convinced ourselves that it isn’t,” Dr. Brenner said. “People have been intimidated from asking that question.”

The mention of the possibility of plant neurobiology elicits such visceral responses that Dr. Brenner said he had at times worried that it could harm his career.

Molly Lambert is managing editor of This Recording

IT'S MY HAPPENING AND IT FREAKS IT ME OUT!

Zooey Deschanel and Marky 'Mark' Wahlberg Diggler in M. Night Shyamalan's Christian Blockbuster The Happening

Daughter Of Two Pastors And Former Christian Rock Artist Turned MySpace Anthem Generator Katy Perry

Andrew W.K. Demonstrates The Fight Face

Gender Double Standards In Media Coverage

Bulbapedia Is Wikipedia For Pokemons

Worst Crap E-Mail From A Dude Ever

Katy Perry Kissing Some Girls, Liking It

"42" - Coldplay (mp3)

"53 and 3rd" - The Ramones (mp3)

"1-800-Suicide" - Gravediggaz (mp3)

PREVIOUSLY ON THIS RECORDING

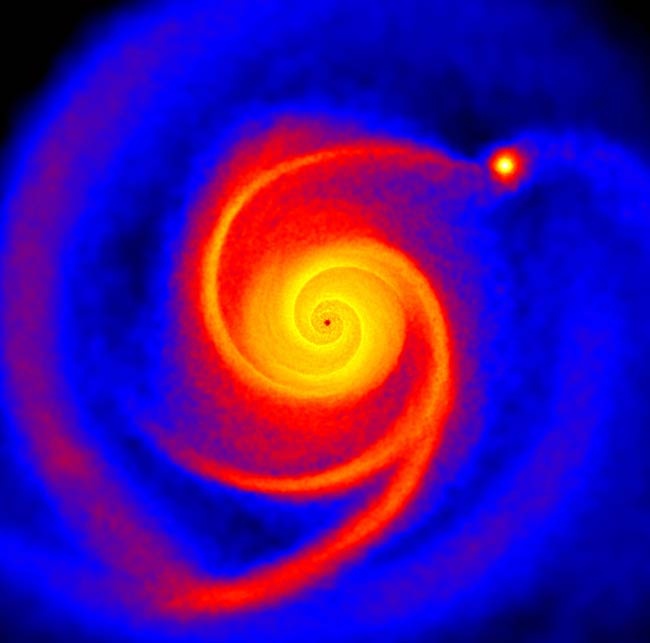

Alex Is A Galaxy

Seeds Of Life On Saturn

Panspermia And H.P. Lovecraft

Thursday, July 3, 2008 at 4:00PM

Thursday, July 3, 2008 at 4:00PM