FILM

FILM In Which We Walked Through Fire To Save Our Lives

Monday, August 14, 2017 at 7:00AM

Monday, August 14, 2017 at 7:00AM

What a Country!

by ALEX CARNEVALE

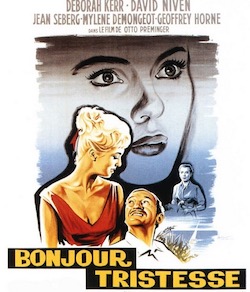

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

dir. Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell

163 minutes

Imagine making the most rah-rah pro-British film in the history of mankind and the British government preventing your distributors from releasing it outside England for a predetermined period of time. Churchill hated Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, although I have no idea why. Were England not such a bizarre and astonishing place that thrives on such contradictions, this would seem sort of Kafkaesque. Maybe the reason it made him so cross is that the film suggests it is a lot easier to admire England from afar - unless you find that over time you have become English.

Imagine making the most rah-rah pro-British film in the history of mankind and the British government preventing your distributors from releasing it outside England for a predetermined period of time. Churchill hated Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, although I have no idea why. Were England not such a bizarre and astonishing place that thrives on such contradictions, this would seem sort of Kafkaesque. Maybe the reason it made him so cross is that the film suggests it is a lot easier to admire England from afar - unless you find that over time you have become English.

There are a lot of jokes about this idea in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Here are some witticisms regarding England that are made in the miniseries-length project, almost all of which I disavow or would insist apply equally to the people of Toronto:

The English can't cook worth a shit.

The English bring England everywhere they go.

The English, when rich, are insufferable.

The English subscribe to their own rules.

The English have poor teeth and limited or awful facial hair.

The English have fantastic women.

The English sometimes patronize or dismiss their fantastic women.

Clive Candy (Roger Livesey) is one hell of a guy with basically zero flaws. He fought in the Boer War, which a soldier in the Great War later dismisses as a skirmish. Upon his return to London, he immediately heads to Berlin to defend England's role in the war. There he meets a woman named Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr). He finds her the utter essence of femininity, and when he observes her body in a striped blue top, he is nearly overwhelmed with a sexuality he expresses by growing a mustache. When she attempts to make Clive Candy jealous by flirting with a German man, Theo (Anton Walbrook), he pretends to be happy for her. She is deeply upset, but because she is English, instead of giving up the game, she marries Theo and bears his two sons. Both boys become Nazis.

In an American film, this would be a serious tragedy that would drive the protagonist to drink or worse. In a Russian film it would be a prologue. In a French film it would be a prelude to a three-way. In an English film, things are likely to get much better – after all, the people involved live in the greatest country on earth!

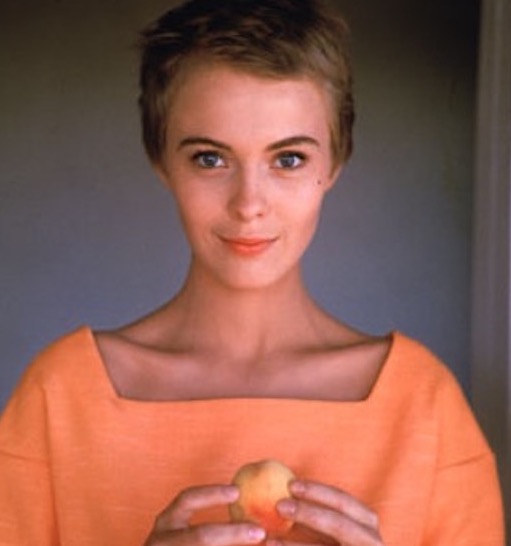

In the film's second act, Clive Candy is still obsessed with this brainy redhead type. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp flashes forward twenty years to the tail end of the Great War, when Candy sees a nurse named Barbara Wynne (Deborah Kerr again) who looks just like Edith Hunter. He marries her, even though he is 40 and she is 20. They have two adorable cocker spaniels, and live in an apartment in London with eighteen rooms. This was Deborah Kerr's first big role after catching the eye of director Michael Powell, who used her as a walk-on in a previous film, and she is spectacular in it. When she initially appears as Edith, you're just so-so on her, because she has these really awful-looking bangs. As Barbara she only lasts about twenty minutes of screen time, but those are twenty of the most special minutes of my entire life.

This is, of course, a metaphorical ideation of England's glee after the war. Meanwhile, Clive Candy's German friend Theo is utterly devastated by his country's defeat, so he becomes a chemist. His wife wants to come back to England, but he gives her a hot "Nah" and they stay in Berlin. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is mostly savage to the German people, pointing out their salacious methods of war, and ultimately framing the triumph of Nazism as the dominance of one way of thinking over a moral but weak Germanity. All I know is that the only Jew in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is the one who wrote the script.

Emeric Pressburger assimilated himself into one hell of an Englishman. Where he is buried, in Suffolk, his is the only Star of David on any grave. (Then again, Jews most often have their own cemeteries.) Pressburger was of a generation with my grandfather Abe, who left Poland when he was a teenager. (He loathed the anti-Semitic Poland that he fled.) Pressburger's private school education was a side effect of his father's wealth, but after his father died, he was forced to make it on his own.

Abe Bernstein never had even a high school education, although he was widely read and laboriously self-taught. He possessed very strong feelings about Europe in general, and especially Germany. (New Jersey was his new mother country.) No one could have been less English than he was, but he admired the English because he could not conceive of one tiny island creating all that culture. (Some of this benign, naive admiration no doubt passed along to his grandson.) There was also a certain cynicism to his respect, however, since I think he was convinced that Nazism never would have been possible without the English. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp suggests much the same thing.

Although the considerable amount of hair on his body testified to his Jewishness, I don't think my grandfather believed in God, and he had good reason to think God had abandoned his people. There is something of that in this film, too, of how those who are not believers see events differently from those who do. Among the many millions that perish over the fifty years this nearly perfect film accommodates, no one ever says a prayer for living, let alone the dead. Like my grandfather, Pressburger put his faith in an historical-economic view of the world. "We'll need to trade with your country," opines Candy to his dispirited German friend, who had spent the better part of the six months following the end of war in the nicest POW camp on record.

As I mentioned last Monday, the Museum of Modern Art is screening Deborah Kerr's best films through August 31. The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is a very long movie, and at some point in the film's third hour, a woman cried out, "And it's still going!" Most of the audience was very fucking annoyed with her outburst, since talking is intensely frowned upon at MoMA screenings. I once saw a older woman who spoke actually pushed by another theatergoer, and everyone around was like, "She had to push her, there was no choice." It's a real tough environment.

Kerr pops up again in the third act, where she portrays Candy's driver, Angela Cannon. For some reason, army fatigues really suit her – probably related to the fact that all redheads look good in green. Candy has lost his wife to cancer by then, and he picks Angela as his driver so he can check her out and be reminded of his only love. In the film's key scene, he states that he never got over losing out on Edith, which is quite the admission considering he never contacted her after she tried to troll him by getting engaged to that German fellow.

Anyway, Pressburger gives Angela a few scenes to establish she is really nothing like the ghost of the woman that Candy admired all those years earlier. Her boyfriend is a really intelligent fellow who is clueless as to how good he has it. This angel was fresh and proud, beautiful and free, and English. God damn was she English.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.