FILM

FILM « In Which We Experience Da Vinci Through The Eyes Of Another »

Monday, February 5, 2018 at 1:50PM

Monday, February 5, 2018 at 1:50PM

Charm with a Negative Sign

by ANDREI TARKOVSKY

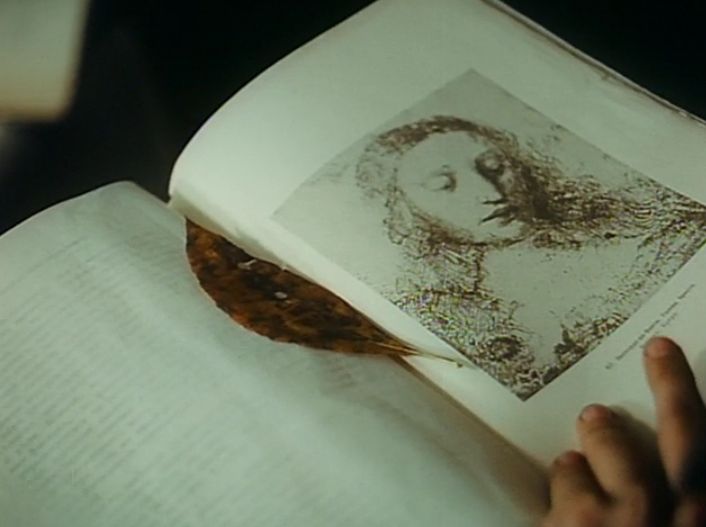

Let us look at Leonardo's portrait of "A Young Lady With A Juniper," which we used in Mirror for the scene of the father's brief meeting with his children when he comes home on leave.

There are two things about Leonardo's images that are arresting. One is the artist's amazing capacity to examine the object from outside, standing back, looking out from above the world — a characteristic of artists like Bach or Tolstoy. And the other, the fact that the picture affects us simultaneously in two opposite ways. It is not possible to say definitively whether we like the woman or not, whether she is appealing or unpleasant.

She is at once attractive and repellent. There is something inexpressibly beautiful about her at the same time repulsive, fiendish. And fiendish not at all in the romantic, alluring use of the word; rather beyond good and evil. Charm with an negative sign. It has an element of degeneracy — and of beauty. In Mirror we needed the portrait in order to introduce a timeless element into the moments that are succeeding each other before our eyes, and at the same time to juxtapose the portrait with the heroine, to emphasize in her.

If you try to analyze Leonardo's portrait, separating it into its components, it will not work. At any rate it will explain nothing. For the emotional effect exercised on us by the woman in the picture is powerful precisely because it is impossible to find in her anything that we can definitely prefer, to single out any one detail from the whole, to prefer any one, momentary impression to another, and make it our own, to achieve a balance in the way we look at the image presented to us.

And so there opens up before us the possibility of interaction with infinity, for the great function of the artistic image is to be a kind of detector of infinity... towards which our reason and our feelings are soaring, with joyful, thrilling haste.

Such feeling is awoken by the completeness of the image. It affects us by this very fact of being impossible to dismember. In isolation, each component part will be dead — or perhaps, on the contrary, down to its tiniest elements it will display the same characteristics as the complete, finished work. And these characteristics are produced by the interaction of opposed principles, the meaning of which, as if in communicating vessels spills over from one into the other: the face of the woman painted by Leonardo is animated by an exalted idea and at the same time might appear perfidious and subject to base passions.

It is possible for us to see any number of things in the portrait, and as we try to grasp its essence we shall wander through unending labyrinths and never find its way out. We shall derive deep pleasure from the realization that we cannot exhaust it, or see to the end of it. A true artistic image gives the beholder a simultaneous experience of the most complex, contradictory, sometimes even mutually exclusive feelings.

It is not possible to catch the moment at which the positive goes over into its opposite, or the when the negative starts moving towards the positive. Infinity is germane, inherent in the very structure of the image. In practice, however, a person invariably prefers one thing to another.

I am always sickened when an artist underpins his system of images with deliberate tendentiousness or ideology. I am against his allowing his methods to be discernible at all.

1986

Reader Comments