Destroy Everything

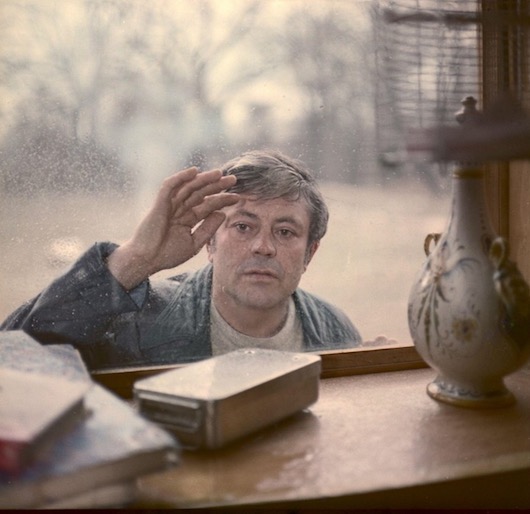

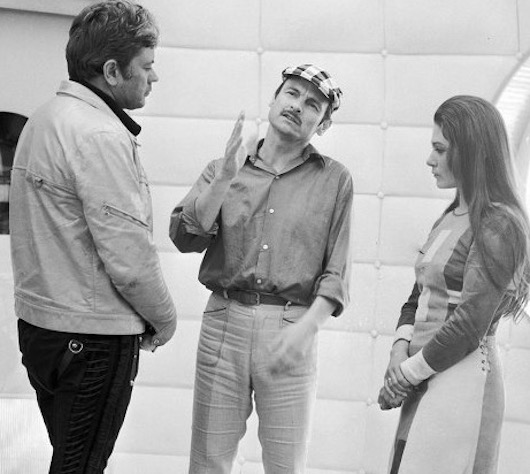

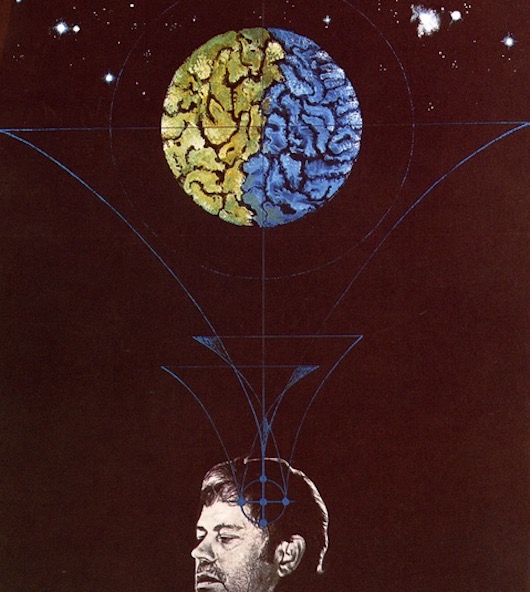

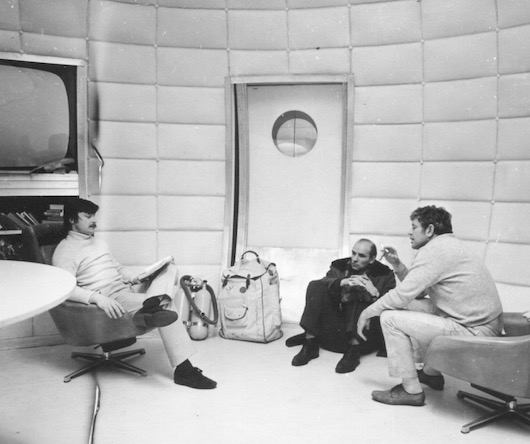

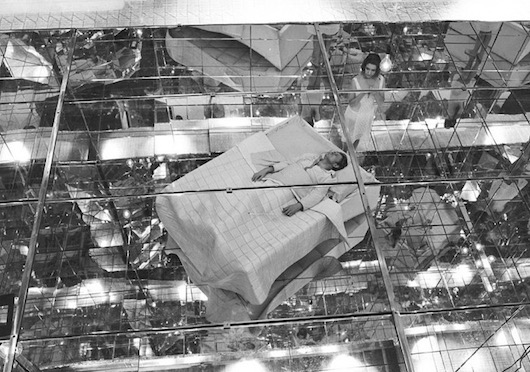

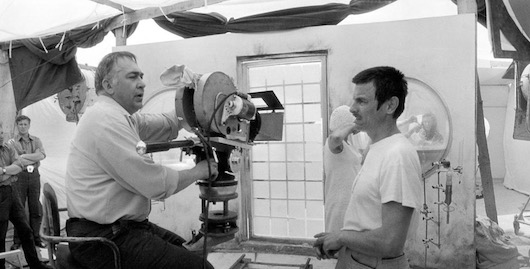

The diaries of the Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky are the notations of a man whose real enterprise was elsewhere. In the 1970s Tarkovsky's frustrations boiled over as he reached the peak of his cinematic powers. Tarkovsky's writing was purely a means to end — a way of framing his real language of filmmaking. As translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair, these notes on films like Solaris, Andrei Rublev and unfinished and unrealized projects reveal Tarkovsky's struggle with the state, his family and himself.

May 10

On 24 April 1970 we bought a house in Myasnoye. The one we wanted. Now I don’t care what happens. If they don’t give me any work I'll sit in the country and breed piglets and geese, and tend my vegetable patch, and to hell with the lot of them!

We shall gradually put the house and garden in order, and it will be a wonderful country house; stone.

The people here seem nice. I’ve installed a beehive. We’ll have honey. If only we could get hold of a pick-up we’d be all set. Now I must earn as much as possible so that we can finish the house by the autumn. It has to be habitable in winter as well. Three hundred kilometers from Moscow—people won’t come dragging out here for nothing.

The two important things now are:

1. Solaris has to be in two parts.

2. Maximum distribution for Rublev. Then I’d be free of debt. And—the agreement in Dushanbe.

To be done in the house:

1. Reroofing.

2. Re-lay all floors.

3. Make second frame for one window.

4. Use tiles from house to roof shed.

5. Make stove for steam heating.

6. Repair cracks in gallery.

7. Put up fence all round house.

8. Cellar.

9. Remove plywood from ceilings.

10. Open up door between rooms.

1 1. Put stove in gallery.

12. Build bath-house in kitchen garden.

13. Make lavatory.

14. Install pump (electric) from the river to the house (if it’s not going to freeze up in winter).

15. Shower (by bath-house).

16. Plant garden.

17. Paint floors and walls of gallery, and beams.

June 3

Yesterday Bibi Anderson was introduced to me. I spent the entire evening wondering if she would make a Khari. Of course she’s a marvellous actress. But she’s not that young, although she looks very well. I don’t know, I haven’t yet decided what to do about her. She’s willing to work for our currency. She’s going to be filming for Bergman through the summer and she’ll be free in the autumn. We’ll see. For the moment I haven’t made any decision. I must talk to Ira.

On the 12th I took Senka to school. My impression was that he had failed, but the headmaster is liberal-minded and didn’t say anything, so for the moment everything is all right as far as school is concerned.

June 12

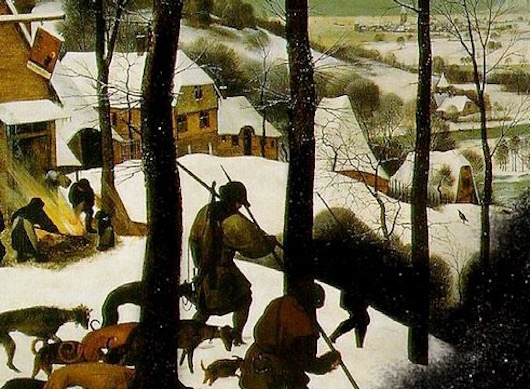

Last night I had a terribly sad dream. I dreamed again of a northern (I think) lake somewhere in Russia; it was dawn, and on the far share were two Orthodox monasteries, with amazingly beautiful cathedrals and walls.

And I felt such sadness! Such pain!

September 18

I saw a very bad film by Bunuel—I forget the name—oh, yes, Tristana, about a woman who has her leg amputated and who some- times dreams of a bell with her husband/stepfather’s head in it instead of a clapper. It’s unbelievably vulgar. Just occasionally Bunuel allows himself lapses like that.

Read Akutagawa’s story about water-sprites — ‘kappas’. Rather mediocre and limp.

Chukhrai asked me to bring them the screenplay of The Bright Day. He wants me to make it with their team. They’re allegedly thinking of buying Ariel as well. We’ll see. I don’t trust Chukhrai. He’s often let people down. Betrayed them.

November 15

I really have to make a note of the fact that on 12 November 1970 I gave up smoking. Frankly, it was high time. The last few weeks I’ve been feeling somehow empty and dull-witted. Either because I’ve been ill, or because I feel frustrated. You could very easily expire without ever having done anything. And there’s so much I want to do . . .

Reading Thomas Mann’s stupendous Joseph and His Brothers. The whole approach is as it were from the far side. Kitchen gossip from the far side. I can see why the typist, as she finished typing out Joseph, said, "Now at least I know how it really happened." Yes, but as for screening it, I really don’t know what to say. For the moment, I don’t see how it would come across.

I want to restore the house in the country — then there’d be some point. Build a bath-house, cultivate the garden. The children could graze. My father came to see us yesterday. He was introduced to his grandson who wore his smart blue suit for the occasion. Please God.

February 18

"Fear of the aesthetic is a first symptom of weakness." — Dostoievsky’s notebooks, about Crime and Punishment, p. 560.

"The supreme idea of socialism is machinery. It turns a person into a mechanical person. There are rules for everything. And so man is taken from himself. His living soul is removed. It is understandable that one may be calm in such Eastern quietism, and these gentlemen say they are progressives! My God! If that is progress, then what is Eastern quietism!’

"Socialism is despair at the impossibility of ever being able to organize man. It organizes tyranny for him and says that is freedom itself!" — ibid., about Svidrigailov, p. 556.

I’m very strongly affected by diaries and archives and "laboratories" of every kind. They’re a wonderful catalyst.

So — Ariel has turned out really well. Only no one must be told what the script is about.

It’s about —

I. The creative pretensions of the mediocre.

2. The greatness of simple things (in a moral sense).

3. The conflict within religion. (The ideal has collapsed. It’s not possible to live without an ideal, no one is able to invent a new one, and the old one has collapsed: the church.)

4. The emergence of pragmatism. Pragmatism cannot be condemned because it is a stage and a condition of society: indeed an inevitable stage. It started at the turn of the century. Life can’t be condemned. It has to be accepted. It is not a question of cynicism. The war of 1914 was the last war to have a romantic aura.

5. Man is a plaything of history. The ‘madness of the individual’ and the calm of the socialist order.

Parallel between Ariel and the turn of the next century. Super-pragmatism on a state scale, as viewed by the man in the street. Consumerism.

I showed Ariel to Klimov, he said he liked it. Whatever happens I must let Yussov have it, so that he can be ready.

August 14

Culture is man’s greatest achievement. But is it more important, say, than personal worth? (If one doesn’t take culture and personal worth as being one and the same thing.) The person who takes part in the building of culture, if he is an artist, has no reason to be proud. His talent has been given him by God, whom he obviously has to thank.

There can be no merit in talent, since it is only yours fortuitously. The mere fact of being born into a wealthy family does not give a person a sense of his own worth and thus the respect of others. Spiritual, moral culture is created not by the individual—whose talent is accidental—but by the nation, as it spontaneously throws out that individual endowed with the potential for artistic creation and the life of the spirit. Talent is common property. The bearer of it is as insignificant as a slave on a plantation, or a drug addict, or a member of the lumpen proletariat.

Talent is a misfortune, for on the one hand it entitles a person to neither merit nor respect, and on the other it lays on him tremendous responsibilities; he is like the honest steward who has to protect the treasure entrusted to his keeping without ever making use of it.

A sense of self-respect is available to anyone who feels the need for it. I don’t understand why fame is the highest aspiration of the artistic confraternity. Vainglory is above all a sign of mediocrity.

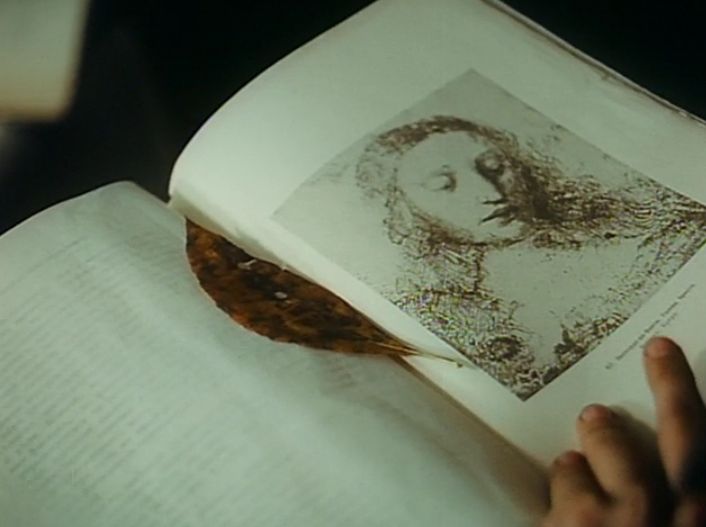

Reading extracts in Novy Mir of S. Birman’s memoirs, with the pretentious, tasteless title, ‘Meetings Granted Me by Fate’. God help us! It’s about Gordon Craig and Stanislavsky. She quotes from a conversation between them about Hamlet, in particular where they are talking about Ophelia.

What rubbish it all is!

Craig’s interpretation of Hamlet is metaphysical and pretentious and stupid. Hamlet as construed by the idiot, megalomaniac Stanislavsky is equally absurd.

At the same time Craig is right when he says that Ophelia falls out of the tragedy, that she is insignificant, whereas Stanislavsky, with one eye forever on the audience because he was scared to death of their verdict, maintains she was a pure, beautiful girl. I’m irritated by this silly claptrap from a silly old woman who wants to attract attention.

August 15

Stanislavsky did great harm to future generations of the theatre; roughly the same as Stassov did for painting. All those lofty ideals — that so-called ‘sense of direction’ as Dostoievsky put it — falsified the functions and the meaning of art.

September 14

Dostoievsky read by the light of two candles. He didn’t like lamps. He smoked a lot while he worked and occasionally drank strong tea. He led a monotonous life, starting off in Staraya Russya (the prototype of the town where Karamazov lived). His favourite colour — the waves of the sea. He often dresses his heroines in that colour.

January 2

If only we could start filming.

February 15

The film was sent to the Committee without any discussion. Sizov telephoned today and said that the film is now much better and more harmonious. But he hinted that there would have to be more cuts. I shall resist them. The length is actually an aesthetic consideration.

I’m going to see Sizov on the 17th; he asked me to; he has to talk to me about something. I can’t bear surprises, they’re always unpleasant.

I am tired. In April I shall be forty. But I’m never left in peace, and there is never any silence. Instead of freedom Pushkin had ‘peace’ and ‘will’, but I don’t even have those.

People are sending me letters after seeing Rublev. Some are very interesting. Of course audiences understand the film perfectly well, as I knew they would.

February 23

Am I really going to be sitting around again for years, on end, waiting for somebody graciously to let my film through.

What an extraordinary country this is — don’t they want an international artistic triumph, don’t they want us to have good new films and books? They are frightened by real art. Quite understandably. Art can only be bad for them because it is humane, whereas their purpose is to crush everything that is alive, every shoot of humanity, any aspiration to freedom, any manifestation of art on our dreary horizon.

They won’t be content until they have eliminated every symptom of independence and reduced people to the level of cattle.

In the process they’ll destroy everything: themselves and Russia.

Tomorrow I’m going to Sizov and he’ll explain what is happening about Solaris. No doubt he’ll try to persuade me and win me over and convince me. The usual story.

I must read the Korolenko story Friedrich was talking about; it’s all about peasant life miles from anywhere in Siberia, and their prejudices and so on . . . It may be a bit like Echo Calls? Screening an existing book is an easier way of doing things.

I somehow think that it’s better to screen inferior literature, which nonetheless contains the seed of something real — which can be developed in the film and grow into something wonderful as a result of going through your hands.

February 26

Late this evening I looked at the sky and saw the stars. I felt as if it was the first time I had ever looked at them.

I was stunned.

The stars made an extraordinary impression on me.

April 2

Evening.

I’m very excited by Zen. At present I’m reading somebody’s dissertation (or simply research notes) about Koan. Very interesting.

"In order to write well you have to forget the rules of grammar.” (Goethe)

"Dostoievsky gives me more than any thinker, more than Gauss." (Einstein)

"We are being sentimental when we attribute more tenderness to a person than the Lord God has endowed him with." (R. T. Blice)

April 6

Here I am forty. And what have I done in all this time? Three pathetic pictures. So little! So ridiculously little and insignificant.

I had a strange dream last night: I was looking up at the sky, and it was very, very light, and soft; and high, high above me it seemed to be slowly boiling, like light that had materialized, like the fibres of a sunlit fabric, like silken, living stitches in a piece of Japanese embroidery. And those tiny fibres, light-bearing, living threads, seemed to be moving and floating and becoming like birds, hovering, so high up that they could never be reached. So high that if the birds were to lose feathers the feathers wouldn’t fall, they wouldn’t come down to the earth, they would fly upwards, be carried off and vanish from our world forever. And soft, enchanted music was flow- ing down from that great height. The music seemed to sound like the chiming of little bells; or else the birds’ chirping was like music.

‘They’re storks’, I suddenly heard someone say, and I woke up.

A strange and beautiful dream. I do sometimes have wonderful dreams.

FILM

FILM  Monday, February 5, 2018 at 1:50PM

Monday, February 5, 2018 at 1:50PM