BOOKS

BOOKS In Which These Novels Thrill All Thinking People

Tuesday, March 8, 2011 at 11:15AM

Tuesday, March 8, 2011 at 11:15AM

Our Novels, Ourselves

Every private library should have a handgun and bidet, for similar reasons. Assembling a distinguished private place for your books is largely the milieu of private people collecting data they've already inputted, in case they should wish for that input to happen again. Now that print is dead, data is all we have. That and unsold copies of The Lexus and The Olive Tree in the discount section of Barnes & Noble. On Thursday we issue our 100 Greatest Novels list, try to be on time. In preparation, we asked young writers and artists to list a few of their favorite novels.

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)

Alice Gregory

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

Of all the boredom-fighting antibodies I have personally tested, The Secret History is the strongest; it obliterates even the most resilient strains of ennui within minutes. I've given it to boyfriends for long flights and family members on bad vacations. It's algorithmically entertaining, like if Dr. Luke wrote a novel. Some hashtags include: Bacchus frenzy, drugs, incest, cable knit sweaters, murder. It's a pretty solid bet for anyone seduced by dead languages or charismatic scholars. Also read Maura Mahoney's 1992 indictment of Donna Tartt. It's great; you can agree with Mahoney's distaste while still loving the book.

The Ambassadors by Henry James

The Ambassadors is a transitional novel; it's the preamble to "late James," which many consider to be incomprehensible and cartoonishly overwrought. But here you'll get a taste for his psychedelic syntax while still being able to read the story without diagramming its sentences. Our middle-aged narrator, Lambert Strether, over-thinks, under-acts, and witnesses the conversations of fin de siècle Paris like a stoned 15-year-old. Experiences seem to pulsate with alternating immensity and insignificance, giving way to "the terrible fluidity of self-revelation." He'll convince you that certain capitalized verbs and italicised pronouns have the power to unlock the universe.

Mating by Norman Rush

One of the prerequisites for reading Mating is indulgent friends. They might block you on gchat and mark your e-mail address temporarily as spam. You will never so thoroughly underline a book or force more quotations on loved ones. The unnamed anthropologist at the center of the novel is a flattering, if sometimes incorrect, model of female subjectivity. Her journey into an experimental Utopian community in Botswana — and her love affair with its leader — inspires rigorous introspection. Norman Rush will get you out of a reading rut, teach you more vocabulary than Eldridge Cleaver, and show you what it really means to intellectualize your emotions. Seriously! It's as good as Moby Dick and Anna Karenina.

Alice Gregory is a writer living in New York. You can find her website here and her twitter here.

Jason Zuzga

In Youth is Pleasure by Denton Welch

If Jean Genet, Temple Grandin, and M.F.K. Fisher were whipped into a exquisitely sensitive gay lad on the edge of puberty just before WWII and left to meander around the grounds and rills of an old hotel in a stifling British summer, where each new hair seen glistens with erotic potential, something like this novel might cut its way free from a chrysalis with tiny bejeweled silver scissors. The actual novel, along with its companions Maiden Voyage and A Voice Through a Cloud, were written by Denton Welch — after he was hit by a car while riding his bike and partially paralyzed at the age of twenty, before his untimely death at thirty-two. Never before or again shall peach melba be described in such a way.

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

Millennia after nuclear volley, humans emerge once more (alas?) into language and consciousness, improvising with shards of speech still eddying among the ruins. The novel is composed in that tattered language, a explosive experiment in textuality not as virtuoso authorial performance (though it is that too) but as constitutive of the arc of tale itself, the reader struggling into mindfulness as brutal Riddley adventures in attempts to think himself into some coherent sense of place and self and purpose. The last pages, an account of adults convened in audience for a trundled-along puppet show, crushed my heart in mournful hope.

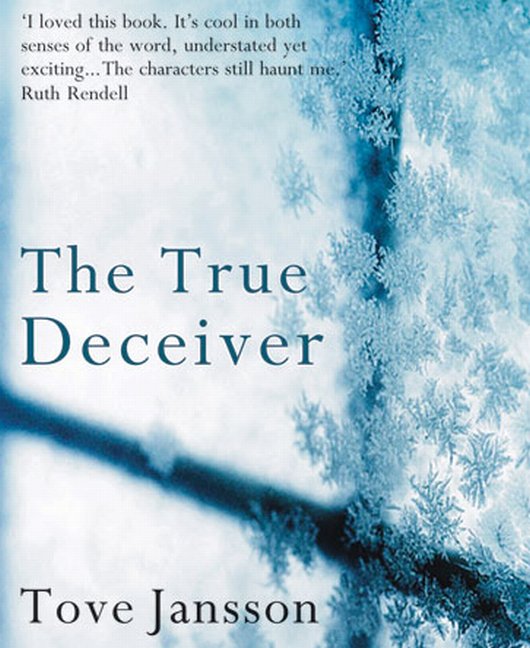

The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson

Jansson is best known for her series of essential children's books about the Moominfamily of Moominvalley, characters that one may get a swift sense of via sampling the Polish stop-motion animations of the tales crafted in close collaboration with the author in the mid 1970s, as in these two excerpts: Sorry-oo and the Wolves or The Hobgoblin Arrives at the Party, etc. In The True Deceiver, a Tove Jansson novel for adults, a strange game of wits cracks through a long scandiinavian winter in a village by the sea between young Katri Kling — good with numbers but bereft of affect, called "witch" by the village children — and local children's book writer Anna Aemelin who fears raw meat and in the short summers paints photorealistic pictures of the forest floor populated with cartoon-like flower-covered rabbits. Over the course of the novel, a dog transforms, a boat is built, contracts with distant licensees of Amelin's characters are renegotiated for better terms, and the rabbits disappear.

Jason Zuzga is a poet and Ph.D. student living in Philadelphia. He is the non-fiction and other editor of FENCE. You can find his website here.

Helen Schumacher

Reservation Blues by Sherman Alexie

In Sherman Alexie’s debut, blues legend Robert Johnson has come to the Spokane Indian Reservation searching for the tribe’s advisor, Big Mom, in the hope that she can help him get his soul back from the Devil. Upon Johnson’s arrival, he’s given a lift by the reservation’s misfit storyteller Thomas Builds-the-Fire and, as a thank you, gives Builds-the-Fire his guitar, who then starts a band and subsequently gets a recording contract in New York City. It's nearly impossible to write fictionally about music and not sound corny, and often Alexie does. But it is a small fault compared to the grace with which he writes about the contemporary life and spirituality of Native Americans on the insular reservation.

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

When I first read Carson McCullers’ "tale of moral isolation in a small southern mill town in the 1930s," I was incredulous of a 23 year old writing something so brilliant and moving. But, looking back now on the novel 10 years later, it makes sense that someone that young would write about anger and idealism and passion with the confidence that she did. As we age, our idealism tends to become a shell of what it once was, and this book is one of our best reminders that it’s a tragedy to give up on our passion, no matter how bewildering it may be to express.

The Quick and the Dead by Joy Williams

A Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2000, Joy Williams’s The Quick and the Dead centers on a pivotal summer in the lives of three motherless teen girls living in the American Southwest: eco-terrorist Alice, increasingly catatonic Corvus, and beauty-obsessed Annabel. As the story expands, it is increasingly populated by an eccentric cast of characters who orbit around each other in a state of limbo as Williams uses her tricky prose to sort the living from the deceased. Her language reflects the character of the novel’s desert landscape, her hard-boiled words both merciless and stunning.

Helen Schumacher is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find her website here.

Andrew Zornoza

The Chrysalids by John Wyndham

"The armour was gone. She let me look beneath it. It was like a flower opening. . . ." The Chrysalids' odd future is a dinosaur: that depressing final hope that refuses to die out, ergo, the Millennium Falcon spinning and Obi-Wan Kenobi, singing: I'm a high-flying astronaut/crashing while/jacking off. . . .

Danny, the Champion of the World by Roald Dahl

Possibly, the truest, clearest, novel ever written and certainly the best guide to fatherhood.

The Green Child by Herbert Reade

An alternative accounting of the sublime, like a historical deconstruction of the obelisk in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Also, one of the worst opening pages in literature — Danielle Steele's Star (She was wearing a blue dress the same color as her eyes that her father had brought back from San Francisco) had more promise.

Crash by JG Ballard

"After having been constantly bombarded by road-safety propaganda, it was almost a relief to find myself in a real accident. . . .” The strange and compulsory reverse engineering of Crash and High-Rise to achieve Empire of the Sun follows an orbital trajectory not unlike one of Ballard's own tragic space pilots, tracing out one of the densest expressions of human feeling onto the tiniest constellation of obsessions.

A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes

An adventure story with cross-dressing pirates; a fevered dream; a study of human and meteorological caprice; and, abridged, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion.

Andrew Zornoza is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is the author of the novel Where I Stay and the forthcoming Forest and Locket.

Morgan Clendaniel

Sometimes a Great Notion by Ken Kesey

Sleeper pick for the great American novel. It's about educated elite versus the working class,the taming of the west, self-determination, the merits and pitfalls collective bargaining, shattered dreams, natural disasters, infidelity, and the relationships between fathers and sons and husbands and wives. (Gatsby is about what? A super rich guy and a car accident?) More importantly, it's the book for ever plaid-wearing, faux-outdoorsmen type who went to a good school and couldn't actually chop down a tree with your decorative axe (that is me, and most everyone I know). Because it's partially about what happens when you're required to chop down that tree anyway, which is a moment of which I think many of us live in both horror and awesome anticipation.

The Odyssey by Homer

I guess this technically predates the idea of novels. But I've found that prose translations — try Butler — that treat The Odyssey more as story than trying to approximate a meter and feeling of verse are actually the best. In those cases, this reads just like a brilliant novel about a man's desperate attempts to get home to see his wife, with some monsters in the way. Most of the things that were vying for spots in my top three just contain plot devices that happened in The Odyssey first, so why not go right to the source?

Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

I read all three of these books once a year. Every time, I find some new detail that I missed before, and it's amazing that Tolkien managed to pack these books so tight with details about the fully-formed worlds. I watched the movies recently, and they pale embarrassingly in comparison. It's a real lesson in the power of the written word and the human imagination: The movies are just flat approximations of something that is so tangible and vivid while you're reading.

Morgan Clendaniel is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an editor at FastCompany.com. He twitters here.

Jane Hu

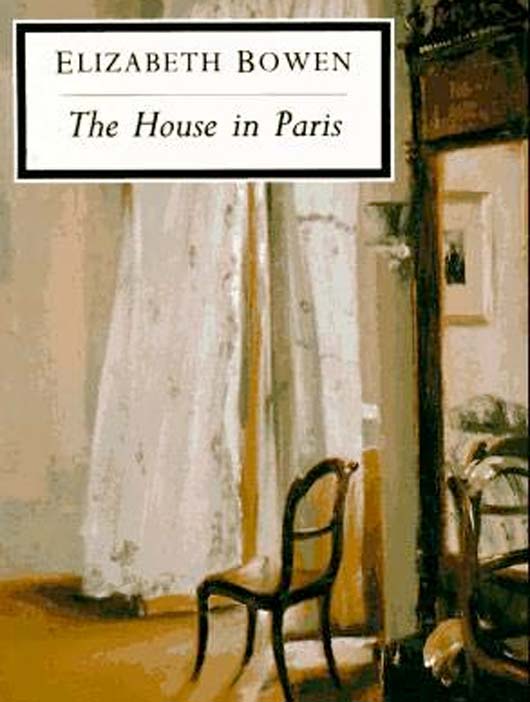

The House in Paris by Elizabeth Bowen

The pitch of this novel is perfect. Two orphaned children, Henrietta and Leopold, meet for one day in a house in Paris while on separate journeys to new homes. The novel is divided, like Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, into three parts — the middle section takes place in “The Past.” Here, we discover the world of romance and intrigue that produced Leopold and subsequently abandoned him.

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Newland Archer and Ellen Olenska’s forbidden affair is one you wished you could had, because their experience of unfulfilled love actually looks richer than any resolved or established relationship. If you’re not crying by the final pages, check and make sure you’re reading the right book.

The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

The bleakness of Faulkner's novels is part of their hopeless beauty, and I will take the desperation of Caddy Compson and Quentin Jr. over Lena Grove’s more hopeful journey always. Introduced through Benjy’s eyes, Caddy is the pure image of love. In fact, every line trembles with love, or poetry. You might not always know what happens in terms of narrative, but you will feel why.

Jane Hu is a writer living in Montreal. You can find her website here.

Ben Yaster

The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass

The Tin Drum's a memorable read for its absurdity — or magic, depending on your attitude toward the diminutive by choice. But what I remember most clearly about this novel wasn't the narrative of stunted Oskar Matzerath's misadventures in Poland and Germany before and after World War II. It's the vivid, surreal details — the eels slithering in and out of the horse's head on the sea shore, the woolly carpet Oskar lays down in the hall of his boarding house, the German pillboxes assembled as if the Axis defense line were a sculpture garden — that have stayed with me. That, and Alfred Matzerath's death upon swallowing his Nazi pin. Just desserts, I suppose.

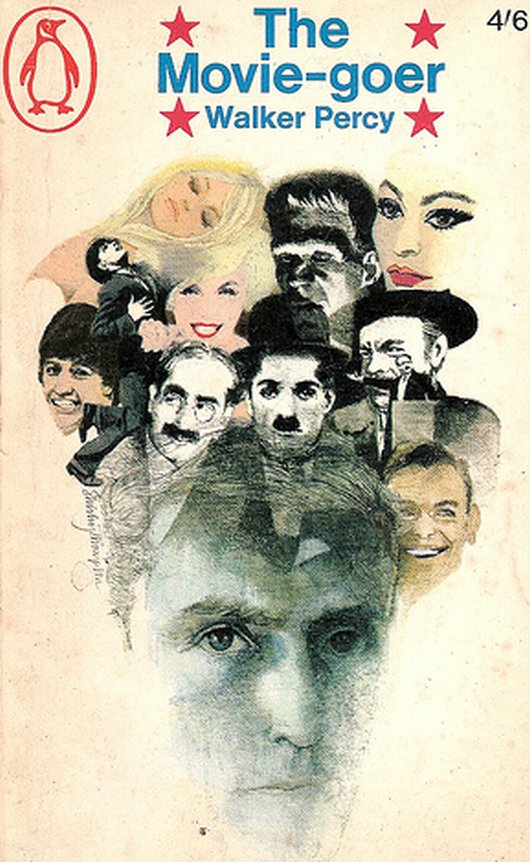

The Moviegoer by Walker Percy

There have been times in my adulthood when the idle waywardness described in The Moviegoer has struck too close. If you're a regular reader of This Recording you've probably felt the same thing. But unlike Binx Bolling, I don't go to the movies because I'm cheap. (I could have practically bought a share of News Corp. for what I paid to see 20th Century Fox's Avatar 3D. This is actually true.) Nor do I lament the passing of the southern gentleman's life of leisure, the birthright stolen from Bolling. When I read this book, I didn't understand it as an expression of existential angst so much as a comeuppance for the patrician set during the rise of middle-class postwar New Orleans. Then again, my mom has given me an unsolicited Nation subscription every year as a birthday present. (This is also actually true.) Whatever your take, this novel is a moving illustration of the sadness of not knowing what you want in life. Folks who recently graduated with humanities degrees can surely sympathize.

Lush Life by Richard Price

Let me cut you off before you begin: Clockers is the better book. I won't argue otherwise. Lush Life resonated more strongly with me, however, because it described something of which I was a part: gentrifying New York. The novel's ostensibly a crime procedural. But the story unspooled is more than a whodunnit. It's a keen examination of urban life and its contradictions, of the permanency of place and the flux of people inhabiting it, of how timeless themes of love and death emerge from the day's pettiest trifles. Don't let me get too lofty, though. It's also a fun, entertaining read, full of wry dialogue and carefully drawn characters. And I've heard that the restaurant was based on Schiller's Liquor Bar. Sounds about right to me.

Ben Yaster is a lawyer and occasional writer. He splits his time between New Haven and Brooklyn.

from a cover for 'The Sea, The Sea'Barbara Galletly

from a cover for 'The Sea, The Sea'Barbara Galletly

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

While most concur about Flaubert’s specialness, generally, and this is the most popular of his books, I imagine many would disagree with me about this choice for best book (Flaubert’s Sentimental Education was more careful still, and more male, and often comes up first for smarter people). But this is, for me, the best book and most familiar. A novel on novels, it is beautifully written, and laden with subtle and less subtle subtext: each word is the mot juste, in as many ways as possible. Each sentence appears almost living, richly embedded with precious aesthetic gifts to you, the reader; but it is also poison, and driving you mad. “She was not happy and had never been,” Emma reflects after another furtive, too-hasty encounter with Leon. “Why was life so inadequate, why did the things she depended on turn immediately to dust?”

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

This novel is no longer my favorite, but it certainly was at one point in college when I was better read. Like all of Iris Murdoch's books, it really pushed me, especially away from it. She is so brilliant and so compelling a writer though that the novel's sum total is worth the angst it will cause to see it through. Amongst other things, Arrowby will teach you something about how to write, and that the contents of memoirs matter very much.

The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas

When I’m trying not to sound like an idiot for choosing the greatest novel ever to be the “best” I call The Ice Palace my favorite novel. Written by Norwegian writer Tarjei Vesaas, it is the story of two young girls who become friends. But it is really a masterfully written story about the complexity of emotions and pain generated during, perhaps as a byproduct of the birth of a relationship between two young girls who are just on the verge of understanding who they will be and where they have come from. And it contains the most stunning description of ice and death I have ever read.

Austerlitz by W.G. Sebald

It is my opinion that W.G. Sebald is the greatest prose writer of the second half of the 20th century. His careful empathy for his difficult subjects is matched by his great ability to adapt modern media and traditional form to fit his stories. In the way that a great poem is neither billable as fiction nor nonfiction, Sebald's complex works transcend the category of novel (or non-fiction). The Emigrants and On the Natural History of Disaster are also great books, but Austerlitz, his last one, he comes closest to the sublime.

Barbara Galletly is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Elena Schilder

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

I read this once at 16 and once at 25. I remember reading the opening as a teenager and thinking that I'd identified some kind of writerly trick — an expansion of human thought and experience so exaggerated as to be comical. The second time I read it everything made me cry.

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

This book created whatever mythic landscape has since existed in my mind labelled "the novel." I'm not sure whether to be grateful for that or not. It is full of bad writing and bad values which probably misshaped my pre-adolescent brain. But I love it; it's what I think they call "juicy."

Home by Marilynne Robinson

I reread this one recently and remembered that it is a really painful book — as in, a book full of pain. The emotional dynamic among the characters stays at an unrealistically high pitch throughout. This is a book about what it would feel like if we were always thinking of other people.

Elena Schilder is a writer living in the Netherlands. You can find her website here.

Almie Rose

Lunar Park by Bret Easton Ellis

American Psycho and Less Than Zero are too obvious, though I love them also. But there is something about this one that I couldn't shake after reading it. This might be his best. It's a fake autobiography of his fake life. It made me laugh out loud: "Without drugs I became convinced that a bookstore owner in Baltimore was in fact a mountain lion." Then suddenly it turns into a horror novel and it's creepy as hell. There's one scene in particular, towards the end, with this thing...I don't want to describe it.

From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg

The best novel about New York ever written. Every time I read it I practically devour it with excitement as it twists and turns into its clever ending. Yes, I know it's technically a childrens' book. I don't care. Raise your hand if you read this and didn't want to hide out in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and bathe in a fountain. If you didn't raise your hand you are missing your soul.

The Land of Laughs by Jonathan Carroll

This book is just bizarre which is probably why I like it so much. It also has the best character name ever: Saxony Gardner. This is the novel I keep coming back to. It's like a mix of David Lynch and Roald Dahl. The main character refers to his father's Oscar winning film as Cancer House. The book is darkly funny and made me want to read every scrap Carroll's ever written. His imagination is so good it makes me angry.

Almie Rose is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Our Novels, Ourselves

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)

If You're Not Reading You Should Be Writing And Vice Versa, Here Is How

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

francine du plessix gray in paris in 1942

francine du plessix gray in paris in 1942