FILM

FILM In Which Ben Affleck Summons Good Intentions

Monday, November 5, 2012 at 11:32AM

Monday, November 5, 2012 at 11:32AM

Argo & the Myth of America

by SHAHIRAH MAJUMDAR

Argo

dir. Ben Affleck

120 minutes

The palimpsest of America’s history and the history of Hollywood illustrate how intertwined the two are in the imagination; how, in powerful ways, they are one and the same and that the myth of the movies is the myth of America: the myth of the hero, that the good guys win, that we are the good guys— and that, though the dark lands beyond us are wild, impenetrable, often unknowable, always we fumble for order, always we grasp for meaning, struggling to emerge as finer, stronger, wiser (if somewhat chastened) selves.

Argo’s opening scenes treat us to a history of the U.S. involvement in Iran’s (and Afghanistan’s) political affairs. Floating above scenes from the streets and the revolution, a disembodied female voice reminds us that the tangled skein of modern geopolitical conflict is shot through with American interventions, secret and overt. The voice itself is a warning – velvet but distant, a quiet survivor’s voice, the accent soft and radio perfect – inflecting nuance and understanding to the senseless scenes of militant students outside the gates of Tehran’s U.S. embassy clamoring for a kind of justice and baying for American blood (#muslimrage).

These scenes are intercut with scenes from inside the embassy: diplomatic staff, pale and hushed, destroy classified documents, hands shaking, fear blanking all emotion in their eyes. As protesters crowd the door, one man –a security guard – decides to be a hero. He’ll go talk to them. He opens the heavy doors in an attempt at civilized negotiation and the next thing we know – these scenes are supremely cut – a gun is to his head; now he is the enemy banging at his own gate. He is his own Trojan horse, punished for his naivety by becoming the entry point by which the militants enter the walls.

It’s an old story to be betrayed by one’s good intentions, for one man’s sincere attempts at heroism to backfire in hellishly spectacularly ways. What’s interesting is the macro and the micro of it all: the man who breaches his own embassy doors becomes an emblem of America. The 52 Americans who are taken hostage for 444 days can be read as a metaphor – if an inexact one – for the many ways that rash American action in Iran, Afghanistan and beyond have led to further chaos and greater global bloodshed, and to a world that feels more unsafe for Americans to be American than it did before.

In the end, however, Argo is a Hollywood movie made by a big Hollywood machine, a big Hollywood star. There is redemption to be offered, a myth to be made, an audience to be assured and entertained, and the enduring figure of the American cowboy to be reified for new American generation. We must be astonished. We must have meaning. We must have our heroes and reasons to go on.

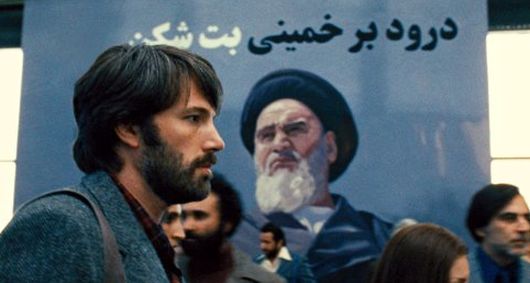

And so a movie whose foundations are littered with the bones of anti-heroes becomes a classic heist flick. The 52 hostages still in the embassy are put on the backburner and the story’s frame tightens around the six Americans marooned in Tehran’s Canadian embassy who must be extracted by Ben Affleck’s lonesome CIA agent: a man with a sad haircut but with a hero’s moral code. Also in the foreground are John Goodman’s Hollywood make-up artist and Alan Arkin’s movie producer. Both are classic types, brash but good-hearted, ingenious in that scrappy American-style and devoted to the idea of a challenge: to the fashioning of a triumphant fiction, however limited the tools. Together, our heroes select a real script (an intergalactic fantasy screenplay called “Argo”) and erect a fake movie, which will become the vehicle by which they whisk the six Americans from under the noses of the Revolutionary Guards.

A script is a powerful metaphor. When Affleck’s agent Mendez plucks “Argo” from the heaped piles of Hollywood hopefuls, it is a moment on which history seems to turn. Why this script and why not another? How, with one gesture, do we choose our fates? Once we set down that path, does it become inexorable? Is it possible to derail the narrative? Or is the script actually a thing that coalesces only in the rearview mirror? Always, all around us, we are choosing and following scripts, sometimes with, sometimes without knowledge of what we do.

When all the movie critics in all the movie rags talk to us about how Affleck the unremarkable actor has buffed brass to gold with his unexpected directing chops, that’s a script from a bag of tricks they have used before. When Mitt Romney talks to us about American exceptionalism, about how America is one of the greatest forces for good that the world has even known, that’s a historically resonant script from which he’s riffing. Obama’s election in 2008 was all about a script we wanted to write for ourselves as a nation. And the Wednesday morning after this election, we’ll wake up to another script about who we are as Americans and what kinds of heroes we envision and need.

In Argo’s script (Argo the Affleck film, not Argo the film within a film), Affleck’s character – our space age cowboy in the Middle East – has a choice to make. When best laid plans starts to crumble and the higher-ups say lets the chips fall where they will, when everything is stacked against him and everyone with power stands in his way, he has to make a decision to do the ethically correct thing. In one whiskey-fueled, dark night of the soul, he makes that choice, of course — though, cinematically-speaking, it appears to be largely dumb luck and Hollywood logic that make the fake movie-crew plan succeed. Argo’s finale is nail-bitingly tense, dense with action, finely wrought, and filled with all sorts of split-second timing decisions that — if they had gone the wrong way — would have led to failure and capture. But this time, when the hero makes the brave choice, no one can stand in his way.

You wonder how Affleck/Mendez’s decision is any different in nature than the embassy guard’s decision at the beginning of the film. The success of both are contingent on circumstances outside of their control. We are given to understand that the guard’s decision was absolutely mad – there wasn’t enough time, or prep, or forethought to make it work– while Affleck’s could lean on long, careful consideration and planning. Yet, qualitatively, we are meant to read both decisions as made on the basis of emotion: decisions made less with the head than with the heart and the gut. Neither man could stand to do nothing. You have to do what feels right. But one fails, and yet the other succeeds. We want to believe that there’s human verity to be extracted from the plan’s success: that there’s right and there’s wrong and that right will triumph. But the lesson from the film’s beginning is that sometimes the script fails us… And when that happens, what can we do?

A few days after I saw Argo, I spoke with a friend who had been young and full of fire in the 1960s and believed in the change that, together, we could bring to the world. She remembers vividly the hostage crisis and what it was like to endure day after day of not knowing what would happen, how it would end, of not understanding why it is that they seem to hate us so. She remembers this as a time when everything felt like failure, a time of great American anxiety about our sense of safety, and the good or evil we could do – or could be done to us – in the world.

Over 30 years later and this breakdown of mood and meaning feels as fresh as ever. Have any of the events that have since unfolded restored America to the longed-for position of hero? How do we help ourselves? How do we help this world be better? Can we, as individuals or as a nation, ever truly be heroes in the sense we want to be? When oh when will we feel safe again? In this age in which the enemies at the gate seem to have become more and more unknowable, is the choice between the script of electing Obama – the introspective guy with a sense of fairness who advocates diplomacy & understanding – and script of electing the hawkish, neo-con-tainted Romney even a choice that effectively makes any difference at all? The fact is that, not only do we have fewer horses and bayonets, but we have fewer cowboys and more (and more dangerous) Indians... Only we call them terrorists now, and they call us the same. (As an American-born Muslim who grew up half here and half in a troubled, insecure Muslim nation, I don’t know how to reconcile who is “us” and who is “them.”)

The film ends with an ode to heroes. There are homecomings. There are medals. There is an elegiac voiceover from Jimmy Carter as a final bracket and a parade of a child’s Star Wars figures that texture the frame. It’s an odd choice — but perhaps what it tells us is that there are no lessons to learn. Perhaps there is no sermon in the suicide. Perhaps the world is arbitrary and Luke Skywalker only a figure limned in plastic. Even when we isolate where things went wrong, how we could have done it differently, is understanding just a story we tell ourselves? And, even if so, isn’t it still a story that must be told? In the end, we turn inward and Argo is about us: about American subjectivity (in fact, there is only one Iranian character, the lovely Sahar, who is granted any subjectivity at all) and how we try to make sense of our place in the world.

If the film asks a lot of interesting questions only to elide them in favor of mostly feel-good answers, what of it? We have our movies, our Hollywood, our myths: the America that endures forever in the rearview mirror. The irony is that it is, after all, Hollywood – all those silly movie people with their foibles and tricks – that offers us something redemptive, that does what a hero does by allowing us, if not to transcend history, at least to transcend ourselves.

Shahirah Majumdar is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about a premonition of enlightenment.

Shahirah Majumdar,

Shahirah Majumdar,  argo,

argo,  ben affleck,

ben affleck,  gwyneth paltrow

gwyneth paltrow