FILM

FILM In Which Joan Didion And John Gregory Dunne Write Together

Friday, August 31, 2012 at 10:16AM

Friday, August 31, 2012 at 10:16AM

In Hollywood

by DURGA CHEW-BOSE

We’ve written twenty-three books between us and movies financed nineteen out of the twenty-three.

– John Gregory Dunne, The Paris Review, 1996

When he was done, the executive asked the writer, “Do you know what the monster is?” The writer shook his head. The executive said, “It’s our money.”

–John Gregory Dunne, Monster, 1997

The millennium is here, the era of “fewer and better” motion pictures, and what have we? We have fewer pictures, but not necessarily better pictures. Ask Hollywood why, and Hollywood resorts to murmuring about the monster. It has been, they say, impossible to work “honestly” in Hollywood.

–Joan Didion, I Can’t Get That Monster Out Of My Mind, 1964

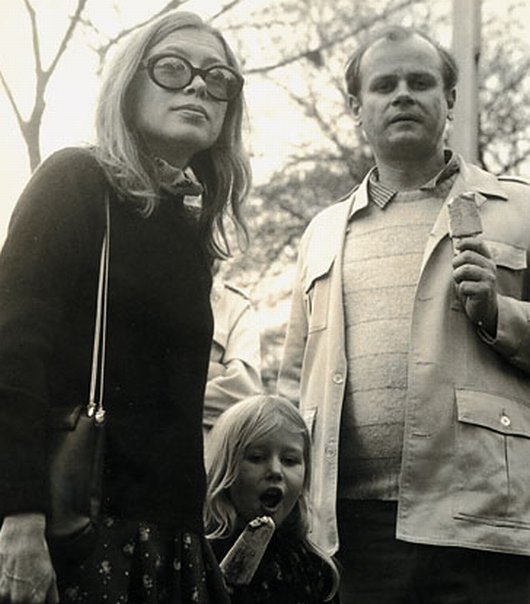

Scriptwriting partners Joan Didion and her late husband John Gregory Dunne had a code for when it was time to cut their losses with a production company and fly the coop. In meetings, while negotiating the terms of a script, if Joan and John sensed the beginnings of disaster — studio dawdling, uneven notes, nonplussed silence — one would look at the other and say, White Christmas. Their choice of words, however, had little to do with Bing Crosby and Rosemary Clooney, with treetops glistening or sleigh bells in the snow. Instead, it relates to Vietnam. As Dunne explains in Monster, his 1997 account of Hollywood’s pecking order detailing the eight-year, twenty-seven-draft saga of Up Close and Personal, Joan and John’s code was a nod to the Fall of Saigon. In April of 1975, “White Christmas” was played by army disc jockeys on the Armed Forces Radio Network as a secret signal to the remaining Americans that “the war was over, bail out.”

John shares this anecdote a quarter of the way through his two hundred page book as part of an epiphany he and Joan have days before his aortic valve replacement surgery in 1991. To a degree, their penchant for weighing a project’s cost imitates Dunne’s expedient writing style. Bottom line? Utility leverages storytelling. Luckily, his reserve of keenly culled nuggets on Hollywood types, like Didion’s and his brother Dominick’s (perhaps the most imbued by celebrity) is never scarce. For every six or so tailored sentences, one diverges and is often marvelous. Hollywood hobnobbing, near spurious hooey.

For instance, at a breakfast meeting with Scott Rudin, the producer detailed to John and Joan a visit he took to Michael Jackson’s Neverland with director Barry Sonnenfeld. Michael was late, en route but still in the air. And so, Rudin kicked back, enjoying the Ranch’s amusement park and zoo. He and Sonnenfeld were invited to stay for lunch and were seated at a table set with expensive linen. They were served ham and cheese sandwiches under silver domes on expensive china which they “washed down with Pepsi-Cola,” as Michael was the company’s spokesperson. For dessert? Bite-sized Snickers in a silver bowl.

Similarly absurd was Dunne’s account of Sunny von Bülow’s room in the Pavilion at Columbia-Presbyterian where John coincidently was recovering. Every afternoon a high tea was served “while a cocktail pianist in black tie played such the dansant favorites as “Send in the Clowns,” and “Isn’t it Romantic?””

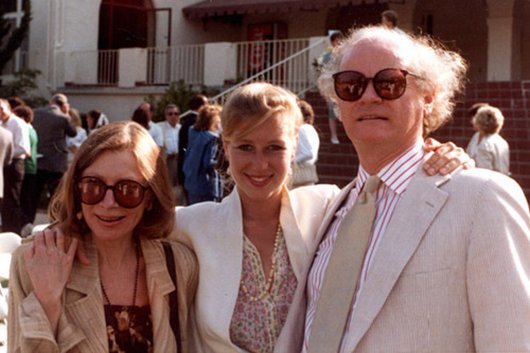

As a quick aside, Sunny had been comatose for close to ten years at this point and her husband, Claus, had been twice accused of attempting to kill her. Incidentally, Dominick had covered the second trial for Vanity Fair, having only written for the magazine once before — a March 1984 piece entitled “Justice” chronicling the trial of his daughter’s killer. Like his sister-in-law, who zeroes in on diagnostic if not sometimes distracting ritz (in Blue Nights, the red soles on her daughter’s wedding day Louboutin’s that showed when Quintana “kneeled at the altar” or Madeleine-type episodes brought on by Saks or the St. Regis) Dominick too, never missed an occasion to mention Sunny von Bülow’s embroidered Porthault sheets.

Despite the Hollywood mixing, Monster is in many ways the ultimate articulation of Dunne’s pragmatic writing style and accordingly, the writer’s and any writer’s inherent nearness to the idea of End. After all, in it he admits that the central reason he and Joan agreed to write Up Close and Personal in 1988 was due in large part to Dunne’s health. Earlier that year John had suffered his first collapse while speed walking in Central Park. “When I regained consciousness, I was stretched out in the middle of the road rising behind the Metropolitan Museum, a stream of joggers detouring past without looking or stopping, as if I were a piece of roadkill,” he writes. Heart surgery was inevitable and as doctors’ visits, tests, and hospital bills were soon to pile — a “very expensive gig” — the WGA’s health insurance became crucial. The deal was closed.

Later in the book, in a rare moment of self-reflection Dunne describes the replacement valve’s clicking sound and how it signified “reassuring proof [he] was still alive.” This newer, louder heartbeat, so to speak, appealed to John’s mortality. So much so that Monster itself is structured around Dunne’s many hospital visits, often yielding for more thoughtful bits as if the narrative, like John, had been ordered to meter the pace.

Even Joan, whose voice is rarely heard in Monster, has her say with respect to John’s condition. One evening, a couple years after John’s surgery while dining at Chinois in Santa Monica, a certain Michael Eisner, who too had had a similar operation, expressed to Dunne that his bypass surgery was in truth “more serious” than John’s. Didion, maddened, immediately shouted, “It was not!” "[She’d] never been an easy fit in the role of the little woman."

The clicking sound of John’s valve resonated with Quintana too who, entertained by the sound, began calling her father the Tin Man. While throughout Monster many friends and colleagues fall ill or die—of old age, of a sudden heart attack, of complications from AIDS, of unhealthy sped up lifestyles—there is an indistinct quality to that last image as both John and Quintana have since died. As though John was writing from his prophetic gut, from that sense of congenital doom and loss that writers are born with, of which his wife described in her 1966 essay “On Keeping a Notebook.” Perhaps it is Dunne’s use of “reassuring proof,” like a child who despite being promised something, commands an actual “Promise.” Or maybe it’s him and her, father and daughter, paired in a single moment, attune to each person’s inherent rhythm. Or maybe it’s simply this reader’s willingness to let the image go there. Either way, the “clicking” abides. It greets the page and far outlasts it.

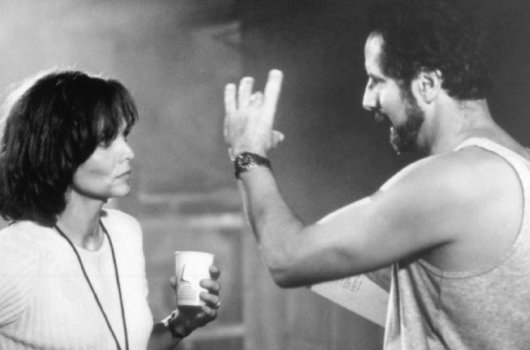

It was John Foreman, a friend and producer, and former Princeton classmate, who first approached Joan and John about writing a screenplay based on Golden Girl, Alanna Nash’s biography of the network correspondent, Jessica Savitch. Five years prior, Savitch had died in a car accident. Martin Fischbein, president of the New York Post, was also in the car. At this point, John and Joan had already written the screenplays for The Panic in Needle Park, Play it as it Lays, A Star is Born, and True Confessions. At this point, they were still incapable of “good meetings,” meaning, they could not schmooze or quicken deals. They were not ‘package’ material and certainly understood that screenwriters occupied an “inferior position on the food chain,” or as Jack Warner (of the Brothers) once said, were thought of as “Schmucks with Underwoods.” But they liked Nash’s book and were ready to proceed with Disney. Or so they thought.

With Disney comes the Kingdom. And with the Kingdom comes the fairy tale. But Jessica Savitch’s story was no fairy tale because in the fairy tale the princess never dies. She is however made over.

Savitch was a woman whose news reporting inexperience was outdone by her ambition. Impelled by some inner fidget, she restlessly wanted more. Her strive had presence, prompting collateral excess. As Dunne describes, she had “an overactive libido, a sexual ambivalence, a tenuous hold on the truth, a taste for controlled substances, a longtime abusive Svengali relationship, and a certain mental instability.” In Disney’s eyes, her “ugly duckling turned golden girl” story possessed too much ugly. Interracial love affairs, cocaine, a gay husband who eventually hung himself, and abortions, were all embargoed narratives. The stuff of Didion and Dunne. A couple who no matter what city they visited, made sure to stop at its courthouse.

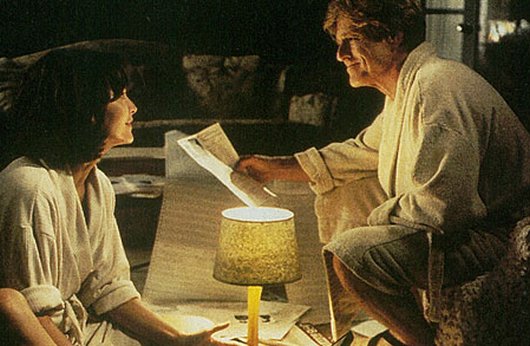

Having come off the success of Pretty Woman, Disney wanted a similarly Cinderella setup. As Dunne puts it, they wanted a Pretty TV Reporter. That is, they wanted a Rodeo Drive sequence, in which instead of swapping sky-high over the knee boots for a polka-dotted polo dress, Michelle Pfeiffer as Tally Atwater would lose her perm and pink blazer for more beige, more poise, and ultimately, the guidance, respect, and love of her news channel director. His name would be Warren Justice — “an appropriately classless first name” — and the role would go to Robert Redford. Near the end of Monster, Dunne fondly remembers one evening when while watching Three Days of the Condor on cable, Redford called him to discuss his character in Up Close. There he was, code name Condor, on Dunne’s television. And there he was too, on the other end of Dunne’s phone. For John, “he was, when all was said and done, Robert Redford.” At a glance, infinite.

But returning to Up Close, where within the first seven minutes of the movie, Pfeiffer clumsily spills the contents of her purse everywhere. Redford, forever wearing a collared shirt, bends down to help her clean up one tube of lipstick, a loose tampon, some change, and a crumpled dollar bill. Nickels, dimes, no Money, and a pair of female things. Pfeiffer is crestfallen, and in her boss’ eyes, nothing but nerves and legs. Within the first ten minutes, he asks her, “Do you always wear that much make-up?” Later he offers her a job as the weatherperson in which she wears oversized clown glasses and a goofy yellow rain jacket and hat.

An early draft of Up Close was given to Mike Nichols who responded with the “graciously noncommittal comment” that his marriage to ABC’s Diane Sawyer created an unfitting atmosphere for any project about TV news. While Joan and John never mentioned this detail to Nichols, Diane Sawyer’s first on air experience at a channel in Louisville, Kentucky, was what inspired Tally Atwater’s debut.

A few years past and not much came of Didion and Dunne’s original Up Close script. In those in between years, Joan worked on her Central Park Jogger piece for The New York Review of Books and John finished Playland. They had meetings with Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer detailed in a section titled, “Bully Boys,” began writing a script in which they called Michael Crichton for advice on string theory, and endeavored incorporating with Elaine May and Peter Feibleman as a rewriting team and company, only agreeing to work on productions that had already began shooting. No more first drafts, no more free meetings or readings; “the meter would start running the moment the screenplay arrived.”

Then Scott Rudin rolled in. Monster is dedicated to him, along with director, Jon Avnet and in memory of John Foreman. Rudin did as Rudin does: he got the movie made. He was “the bully boy’s bully boy.” But most importantly he offered Dunne the most producer-ly advice ever. When asked by Dunne what he thought the movie was really about, Rudin, forever skewed to money and éclat, answered, “It’s about two movie stars.”

Which briefly brings to mind Aaron Sorkin’s HBO drama The Newsroom. Rudin is an executive producer on the show and one cannot help but wonder if he gave Sorkin similar advice. The show, much like Up Close is less about the news and more about the dopey hearts of those involved. Basically, it too is centered on two or more “movie stars.” The newsroom is their stage and so far, their love entanglements are its crux. Everything else is merely crosstalk. Women with alliterative names in silk shirts flail their arms, stutter, shriek, and may as well be spilling the contents of their purses everywhere. Meanwhile, the men speak in sports metaphors, are romantic dolts, and threaten to congratulate their female coworkers for having gumption and good ideas. Music swells, smug smirks are protracted. Sorkin, forever the guy who writes soap operas about guys on their soapboxes.

While Rudin did push for more romance in Up Close, reminding Joan and John that it was a love story after all — to “deliver the moment, deliver the moment” — John was adamant about one thing. He told Rudin, “I don’t do love.” Thing is, composer Diane Warren and Céline Dion sure do. Avnet hired both and the song “Because You Loved Me” came to be. Number one in the United States for six weeks, its music video featured Céline in a makeshift control room performing with burning credo as clips of Pfeiffer and Redford, punch-drunk and sweet for each other, fade in and out. Today, sixteen years later, clips of Emily Mortimer and Jeff Daniels’s Mac and Will could comfortably replace those of Tally and Warren.

While an appraisal of Sorkin, Dunne and Didion, all in one breath, is slightly offhand, it does invite a closer look. In October 2011, A.O. Scott did exactly that for his review of Bennett Miller’s Moneyball, which was co-written by Sorkin. In it, Scott opens by referencing Didion’s 1988 New York Review of Books piece on the presidential election entitled, “Insider Baseball,” published mere months before she and John agreed to write Up Close. “The process” as she explains and as Scott quotes, is “not about ‘the democratic process’ or the general mechanism affording the citizens of a state a voice in its affairs, but the reverse: a mechanism seen as so specialized that access to it is correctly limited to its own professionals.” As Scott spells out: narratives that function as “durable forms that cater to this appetite for exclusive knowledge, inviting the reader or viewer to learn something about how the professionals do it and to feel vicariously, like one of them.”

Sorkin’s breakneck dialogue deals with characters, mainly men, who run countries, television networks, professional sports teams, who invent algorithms in order to make friends and humiliate girls. As Scott points out, these characters are all, by some means, a performance of Didion’s sentiment. They claim “specialized” speak, when inevitably the tensions return to sex and money, and winning. Proximity to transparency, to insider-y yackety-yak, assumes entrance. And yet, as Didion reminds, “what strikes one most vividly about such a campaign is precisely its remoteness from the actual life of the country.” Her remarks about the electoral process could be applied to Sorkin’s Zuckerberg, to Will McAvoy, President Bartlet and Billy Beane: “These are people who speak of the process as an end in itself, connected only nominally, and vestigially, to the electorate and its possible concerns.” All that walking, all that talking.

Interesting then to examine Dunne’s Monster, which in many ways is the ultimate insider’s look into Hollywood’s process. Written from the vantage point of someone who was involved from the very start, from meetings to rewrites, rewrites to more meetings. From the Beverly Hills Hotel where Nora Ephron, who was staying across the hall, volunteered business advice or to Tony Richardson’s Bonjour Tristesse-type St. Tropez hamlet — Le Nid du Duc — where his daughter, the late Natasha ‘Tasha’ Richardson was once a chain-smoking teenager who wore a micro miniskirt and as Didion writes in Blue Nights, “devised the fables, wrote the romance.” Or back in LA, a few years later, for the funeral of Tasha’s father and a gathering of friends in his Hills home — the Kings Road house that once belonged to Linda Lovelace. The list of trivia goes on and on. Who, what, when, where, why, how, Hollywood!

John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion were deeply embedded in the “private idiosyncrasies of very public people.” As Dunne affirms, he was simply there — “the reporter’s justification for what he does.” Surely, Sorkin could sniff out his next script there too. Didion and Dunne’s ‘White Christmas,’ an elucidation of what A.O. Scott terms the “half-secret language…a body of artisanal lore.”

It was recently announced that Didion would be penning a script with Todd Field. Todd Field who wrote and directed In the Bedroom and Little Children, and who in Nicole Holofcener’s 1996 Walking and Talking, proposes to Anne Heche’s character by hiding the ring in her round birth control pack.

As a filmmaker, his movies look like worlds Didion might mine: tortured, grieving parents in one, and the crepuscular, discontented mood of middle-class suburbia in the other. Both films are literary. Both films portend menace, as if from the opening credits, somebody has a hunch. Both are carefully constructed — quiet and sustained like a yawn. Both are all whites, pale blues, and greens, with freckled, sun kissed skin. In both films, light filters through windows no matter how melancholic the scene. Even each poster’s plain serif font: exactly bookish. Precisely Joan. And yet, no matter how ideal the pairing of Field and Didion, Dunne tolls — that “clicking” sound, sounds. Her all white office; his wood-paneled office. His, hers. His first draft and her reworking of it. “The version the studio sees is essentially our third draft,” Dunne told George Plimpton. He went on to share that he and Joan, before beginning any script, would watch Graham Greene and Carol Reed’s The Third Man. “The best collaboration between writer and director I can think of.”

Monster, despite little emotional bulk is nostalgic by nature. Eight years, twenty-seven drafts, and two presidential elections later, John wrote it as though summoning memories at a table of close friends, far into the night, long after dessert was served and more drinks were poured, at that delirious hour when leftovers are pulled out of the fridge, unwrapped, and eaten without plates. One gets the sense he could have written twice as much. One gets the sense his memory was trained to pocket stories, not for sentimental reasons, but because he knew what he was seeing, others would savor. His account is entirely generous, if not a little boastful. His last words, “We also had a good time,” belong sincerely to Joan.

Durga Chew-Bose is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here and twitters here. She last wrote in these pages about Mariel Hemingway.

"Leaving Pieces" - Triste L'Hiver (mp3)

"Spiral Blue" - Triste L'Hiver (mp3)