BOOKS

BOOKS In Which Daphne Du Maurier Marries Young

Tuesday, December 29, 2015 at 10:32AM

Tuesday, December 29, 2015 at 10:32AM

Little Points

by ELLEN COPPERFIELD

Daphne du Maurier's father was convinced his line would end with him, given that he fathered three daughters, and his only brother was killed in the world war. Gerald du Maurier hated being an actor, and occupied himself by plowing young actresses between scenes.

Daphne spent a lot of time with her father; things were cold and contentious with her mother for a long time. At first Gerald concealed his indiscretions, before openly introducing his conquests to his daughters. Perhaps Daphne had sensed them.

Daphne wished she had been born a boy, explains Margaret Forster in her sterling biography of the writer, Daphne Du Maurier: The Secret Life of the Renowned Storyteller. I It would have made her father happy, and ensured she could do whatever she liked. She called her male self "Eric Avon." Eric was a lot more like her father than she would probably care to admit.

She was a restless and unhappy teenager, quickly disgusted by the London environment she inhabited, all blue eyes and boyish shirts. When she first received her menstrual cycle, she named the flow 'Robert.' "The future is such a complete blank," she told her governess. "There is nothing ahead that lures me terribly. If only I was a man."

She judged her parents' marriage quite harshly, given that her mother knew of her father's cheating and accepted him despite it. Her father was a successful actor, and the du Mauriers were quite wealthy.

Gerald du Maurier was friends with J.M. Barrie, whose acquaintance gave Daphne the idea to start writing. She had virtually no friends her age, and was completely within herself. "I only think of myself and pity anyone who likes me," she wrote. Her parents sent her to finishing school in France, hoping she might figure things out there. The school was quite austere in comparison to what she was used to, but Paris caught her attention right away.

A teacher named Yvon took an erotic interest in Daphne, who became her pet. She could not think of herself as a homosexual, since her father hated gays. Identifying herself as male is the only way she could make sense of her feelings. She more than liked the attention from Yvon, who was rather handsy with her.

Daphne was 18 when she went on holiday with Yvon, who had just turned 30. Things never got overly physical, but time relaxing with a hardcover copy of Katherine Mansfield's latest and a woman who loved her reassured Daphne that things were not all bad. She only loathed the idea of going back to England and living with her family again.

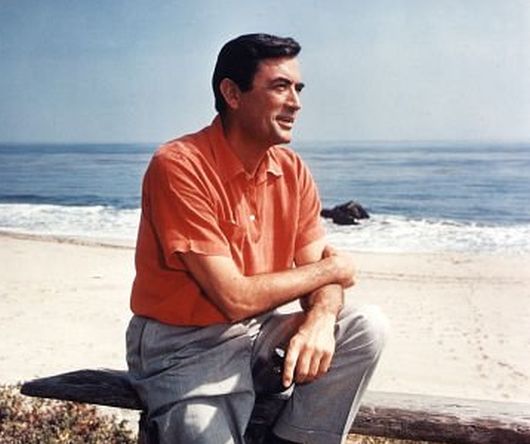

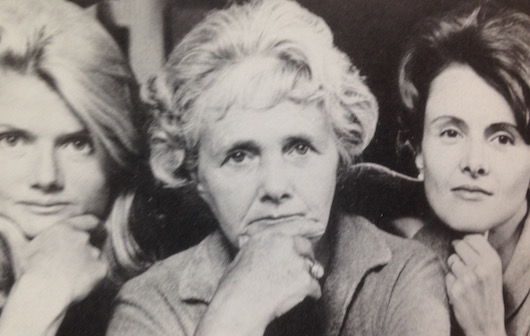

Daphne, right, with her sisters

Daphne, right, with her sisters

She knew that in addition to being attracted to women, she also found something compelling in men. Her father did not accept this proclivity, displaying extreme jealousy when she emerged for or returned from a date. Gerald told her that he wished he were her brother, not her father, and that if he died he would enjoy returning as her son. Her father's possessive attitude pushed her further into literature. She had completed three stories; all of them concerned bullying, disreputable men.

Distancing herself from her father, Daphne learned to sail. She put aside writing and supervised the construction of her boat, which was to be called the Marie-Louise. It was then that she met her first boyfriend, Carol Reed. Together they smoked in cafes and observed other people. Reed reflected her moodiness, and was just as capable of doing something rash out of nowhere. She was 22 when she and Carol fucked for the first time.

with her first child, Tessa

with her first child, Tessa

Carol immediately began to take the relationship with the utmost seriousness, a development that frightened Daphne. Carol ensured he would stay around by praising Daphne's writing; her former teacher Yvon told her that her stories proved Daphne would never achieve anything. To get her away from Carol Reed, Daphne's parents secured her a quiet cabin for the summer, where she was to focus on her writing.

In was in this setting, consistently decimating the marital hopes of Carol Reed, that she wrote her first novel, The Loving Spirit. This melodrama is clearly an early effort, and it is mostly in du Maurier's prose style itself - effortless and clear — that we recognize her distinctive way of saying something was so.

Reading The Loving Spirit today is quite a struggle, but for the time it was an advanced work from a writer with no advanced training. Her second novel, I'll Never Be Young Again, was a clear measure ahead of her first effort, using a strong first person voice to create her first ghostly effect. Rebecca West called it "a whopper of a romantic novel in the vein of Emily Brontë," which was almost, but not quite, a backhanded compliment. But hey, Daphne du Maurier was just 23.

Daphne's ideas about everything changed when she met Frederick Browning, known to his friends as Tommy. Browning's service in the war had traumatized him plenty — it took him a good six months to work up the courage to even enter battle. Once he became a career man, he never left. Even stricken as he was with PTSD, Browning was a quite attractive 34 year old man.

At first Daphne was reluctant to commit. "It will take at least five brandy-and-sodas, sloe gin and a handkerchief of ether to push me to the altar rail," she claimed, before proposing to Browning herself. The wedding took place in the middle of July, and her parents gave them a cottage as a present.

Six months later, Daphne was pregnant with her first child, a girl named Tessa. She stopped breastfeeding as soon as she could: "The child hiccups most of the time and kicks me in the stomach. But then I never was sentimental." Daphne suffered from postpartum depression, and struggled to bond with her daughter. The strains of her marriage wore on her, too. Browning was in Surrey when she was at home, and she felt adrift.

Then her father died. Daphne did not go to the funeral, and fantasized she saw her father as a ghost. She channeled her grief into a monograph about her father entitled, Gerald: A Portrait, which managed her best reviews yet. Her new publisher was Victor Gollancz, and under his encouraging influence she began the novel which would become her first solid hit: Jamaica Inn.

Just as she was achieving her largest public response to date, her husband's service took them both to Egypt. She loathed the city of Alexandria, feeling confined to a scrubby house since there was simply no place where she could realistically walk. After giving birth to a second daughter, Flavia, she decided not to return to the country. Yet it was in this inharmonious setting where she would conceive the idea for her next novel, "a rather sinister tale about a woman who marries a widower."

Rebecca was slow in emerging from Daphne's brain. Initially, Daphne trashed the first 15,000 words of the manuscript and began again. In a new house in Hampshire, she finally found the routine she needed. Servants handled her children while she focused on her new book. "It's a bit on the gloomy side and the psychological side may not be understood," she worried to Gollancz. Rebecca became instantly popular in England, but it was a smash in the United States.

in her writing room

in her writing room

Daphne felt a bit confused. She had a full family to fear for whenever her husband started repeating his predictions of a Europe hurtling towards war. She expected her kids to lead quiet lives where they expressed their inner imagination. Instead, Tessa and Flavia could be loud and disobedient like any children, and Daphne disapproved of this behavior. "Instead of thinking my children are marvelous, I am super-critical," she told her mother.

Disgusted by the film version of Jamaica Inn, Daphne attempted to construct a version of Rebecca that might play well on the stage. As war came to London, she refused to send her children to America, fearing she would never see them again. Instead, she had a third child, a son they named Christian.

her friend Ellen Doubleday

her friend Ellen Doubleday

Depression was a feature of her everyday life, though she loved her son in a way she had never felt close to her daughters. She felt distant from Browning and resented their many weeks apart. She was, however, finding herself as a a mother. "I am very grateful for being given the power to deal with all these little domestic worries," she wrote, "and I am sure it has been a discipline. I've always shirked responsibility before. Now I find I can bear it. I seem to know the children more through looking after them. God is testing me out on those little points."

With her husband away, Daphne flirted with a family friend so much their relationship became a bit of a scandal. There was no sex, only a connection that evaporated both of their marriages. She wrote a book about the man's family called Hungry Hill. It was her husband's glider accident that wrecked his shoulder and returned him to her. Nursing him back to health effectively ended Daphne's infidelity.

After the war, when Browning came back to the family for good, he did not want Daphne anymore. The pain of the rejection stung, and abandoned them to separate beds, where each barely slept. "If Tommy just looks upon me as a dull old thing he is fond of, the outlook is dreary," she confessed to a friend. Browning's drinking made it impossible for him to get an erection in any case.

In America for the first time: Daphne was there unwillingly, forced to defend herself against charges of plagiarism that were focused on Rebecca, a story so old it could properly be called a fable. She won the case and left as quickly as she could, but not before developing a crush on the wife of publisher Nelson Doubleday. It could never be consummated, but she wrote the woman as many letters as she could.

Too much had gone on since she had married Tommy. She saw an older man who barely knew his children, grew frustrated at the first moment his oldest daughter was not what he expected. His strangeness with his own blood only made it less likely he could ever be close to Daphne, and she resented that he did not even make the effort, that there had been no homecoming whatsoever. He had brought a young girl with him, in fact, his war secretary, in her twenties. Daphne found her beautiful.

She was not happy, and every person in her life could tell.

Ellen Copperfield is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. You can find an archive of her writing in these pages here.

"I've Known For Long" - Alberta Cross (mp3)