MUSIC

MUSIC In Which We Were Born Like Jeff Buckley

Thursday, March 27, 2014 at 11:39AM

Thursday, March 27, 2014 at 11:39AM

Creative Inertia

by KARA VANDERBIJL

Jeff Buckley’s brief intro before launching into a cover of “Dido’s Lament” is murmured in a ghost’s timbre, barely outdoing the white noise on the recording even at highest volume. His audience laughs, spooked, then the piano opens. “Thy hand, Belinda,” Jeff sings.

His is a freakish voice, made all the more odd by the grainy quality of the recording; a high falsetto mimicking the dramatic mezzo-soprano for which Purcell wrote the aria. He wails — his voice almost breaks, but doesn’t. Listening, we want it to break; the melody is too pure, its perfect desperation too stringent for this wild, unpredictable thing. Remember me, forget my fate.

It is this drama, the constant rediscovery and redelivery of a familiar, worked-over, oft-repeated tune that defines Jeff Buckley’s work. Like his voice, each song defies an original genre or mood, turning back to a more primal source. Is it a lament? A mockery? A strange self-issued prophecy from a man who, two years later, would walk into the Wolf River in Memphis, TN and drown?

Like many of his other performances, this one (a set at the 1995 Meltdown Festival in the UK) now only exists on the web, maybe even on fragments of a video somewhere. Had Jeff Buckley lived past the age of 30, it might have remained among the other, less-than-perfect detritus of a long and successful career. But when the talented die young, we like to watch their home videos. Their unprotected moments. Their failures, blow-ups, fuck-ups. Anything that might give us clarity about their end: what “brought them to this point.” Short of simply accepting that it was death that did Buckley in, we might say it was the success that got him.

Only four years earlier, Jeff had sung in public for the first time, at a tribute concert for his estranged father Tim Buckley. They had met once, when Jeff was eight, after one of Tim’s shows; two months later, Tim overdosed on heroin. Neither Jeff nor his mother Mary Guibert were invited to the funeral. When Jeff stepped onto the stage at Saint Ann’s in Brooklyn to sing Tim’s “I Never Asked to Be Your Mountain”, most people weren’t aware that Tim had a son, and most people who knew Jeff didn’t know he could sing — he’d patented himself, stubbornly, as a guitarist — so the evening unveiled not only Jeff’s vocal talent but also exactly where it had come from. This pissed Jeff off. If anything, he had hoped to use the brief set as his way of paying his respects, of breaking away from Buckley senior.

Years later, when a fan shouted a request for one of Tim’s songs, Jeff looked her straight in the eye and said, “I don’t play that hippie shit.”

Jeff escaped his hometown of Anaheim, leaving behind what he described as a “rootless trailer trash” existence. He’d been struck by New York fever. Over the next year and a half, he played at coffee shops and nightclubs in Lower Manhattan, and eventually earned a regular Monday night slot at Sin-é in the East Village, accompanying himself on the guitar. He covered Bob Dylan. Nina Simone. Van Morrison. Once, singing “Sweet Thing” with Glen Hansard, the still-obscure Buckley drew a crowd by taking the second verse through a series of vocal gymnastics that lasted fifteen minutes. People outside the club began pressing up against the window to hear him perform.

A brief writing streak with Gary Lucas resulted in two original songs, “Mojo Pin” and “Grace”, that Jeff nevertheless rarely played in his set. Lucas also invited Buckley to perform in his band, Gods and Monsters, early in 1992. By that time, however, the streets outside Sin-é were lined with record label executives hoping to snag Buckley for a solo album. That October, Buckley signed with Columbia, hired a drummer and bassist, and recording for what would be his first and only studio album, Grace, began the next summer. A quick EP, Live at Sin-é was released in November ‘93, documenting Jeff’s coffee-shop years, a time he’d long for intensely almost as soon as he left it.

Jeff was not prolific; of the ten songs on Grace, he penned only three on his own. Lee Underwood, Tim Buckley’s guitarist, said once that Jeff suffered from an all too-relatable sort of creative inertia. “[He] felt uncertain of his musical direction, not only after signing with Columbia, but before signing, and all the way to the end. He did not know himself — which musical direction he might want to commit himself to, because taking a stand, making a commitment to a direction, or even to composing and then successfully completing the recording of a single song, was extremely difficult for him. One the one hand, creativity was his calling. On the other hand, any creative gesture that offered the possibility of success terrified him.” To speak nothing of the looming shadow of a father he never spoke of, to whom he was inevitably compared, as well as a sort of dogged perfectionism that plagued his studio sessions.

Spending hours, as he did, overdubbing the vocals until he had reached what he felt was the optimal delivery, Jeff seemed reluctant to pin any one mood onto his work. Andy Wallace, Grace’s producer, had to piece several of the songs together from dozens of takes. The music was in constant metamorphosis, to the point where later, live renditions of the songs sounded different, singular, wed to whatever Buckley had learned or felt or needed in between one performance and the next. He seemed to rewrite them each time.

Grace is disparate, wavering between the almost cacophonous landscapes of “Mojo Pin”, “Grace”, “Last Goodbye”, and “Eternal Life”, the hushed, sacramental “Corpus Christi Carol”, and the desperate “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over”. Buckley alternately whispers or wails, seems to laugh and growl, shreds remarkably. The music is a story as emotionally complex as its author — calling it simply brooding or romantic minimizes its scope. In reality it is confused, mystifying, indecisive.

The album, like the EP preceding it, sold in a slow trickle. Jeff’s songs rarely made it to the airwaves. Critics were either charmed by its triumph or turned off by what, altogether, seemed to be a confusing melange of emotions and genres. The French loved it, though, and in 1995 awarded Jeff with the Grand Prix International du Disque, an honor he shared with the likes of Edith Piaf, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, and Bob Dylan. David Bowie claimed that Grace was the one album he’d want with him on a desert island. Meanwhile, Jeff silenced restless crowds in concert halls across the globe with a few strums of his guitar, with a Buddhist-like opening chant called “Chocolate” that hushed chatter until you could hear a pin drop. Only then would he break into “Mojo Pin”.

Putting Buckley’s cover of the Cohen song in a separate category — as I undoubtedly must — “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over” is Grace’s masterpiece. Jeff introduced it first at Sin-é when he signed with Columbia, luring listeners who had previously doubted his ability to produce a decent song of his own. Back then it was just Jeff and his guitar, sans the divine harmonium intro, the swelling gospel choir, absolutely pure. Lyrically, it’s as seductive as it is sad — as Jeff escalates to “It’s never over/my kingdom for a kiss upon her shoulder,” a tingle begins deep down. It’s as much the power of his voice as the power of his poetry. He chokes it out, like an old love letter he’s been forced to read aloud.

I will say this about “Hallelujah” — everything blooms from the single, conquered breath that opens it.

Buckley is remembered for these quieter contributions, and appropriately so; in a way they serve as auto-epitaphs. An incredible mimic, he nails Nina’s voice during brief moments in “Lilac Wine” and rivals any choir boy with Britten’s “Corpus Christi Carol”, which had been introduced to him by a friend in high school. But it’s palpable anger that colors the rest of Grace, anger that Jeff would take with him on tour and into the beginnings of his second album, My Sweetheart, The Drunk. He butted heads with the bigwigs at Columbia when he refused to make a music video. He alienated friends, his photographer Merri Cyr, and some of his strongest supporters with careless words. Seamlessly integrated into his public image were frequent moments of conflict, uncertainty, and stubbornness, most of them related to his burgeoning fame, and almost always triggered by casual comparisons with the late Tim Buckley.

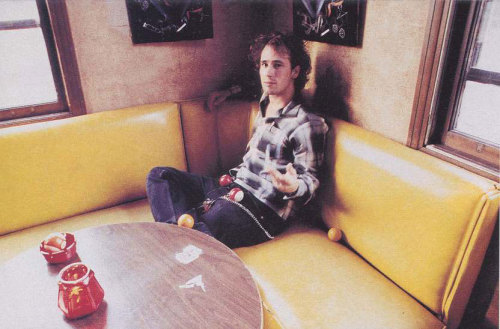

When People Magazine nominated Jeff as one of their “50 Most Beautiful People” in 1995, something snapped. He dyed his hair black and stopped washing it. He wallowed, thin, in giant thrift-store plaid shirts and Doc Martens. On stage, Grace changed: “Buckley and the band were now playing harder, faster, and louder than ever before, transforming slow-burning epics — ‘Last Goodbye’, ‘So Real’, ‘Eternal Life’ and the title track — into rock and roll firestorms that bordered on the metallic. ‘Mojo Pin’ circa 1996 was almost unrecognizable: Buckley screamed so hard as the song built to its thunderous climax that you feared he’d cough up a vocal cord,” wrote Jeff Apter, one of Buckley’s biographers.

Touring took its toll on Jeff; he needed peace and quiet to work things out, to create, but the frenzy of the road worked up a hysteria in him. Once, in Ireland, he disappeared for a few hours in the afternoon and walked around singing and playing guitar in the pouring rain, skipping interviews and a sound check. Another time he arrived so drunk on stage he broke into a rendition of one of his father’s songs. Yet another time, wasted, he fell asleep underneath a table at a show in Manhattan. Another musician would have been thinking of giving the public a second album to chew on; Jeff was just trying to stay alive. Returning to New York in 1996 after two years on the road, he found the Village, which had once afforded him the comfortable hum of cappuccino machines, the safety of coffee shop anonymity, completely transformed. Sin-é had closed its doors. What few shows he did play, he had to advertise under pseudonyms. He needed a quiet spot, a shrine. So, in early ‘97, he went to Memphis.

During the last few months of his life, Jeff Buckley lived in a shotgun house which he rented for a paltry $450 a month. He owned little more than a couch, a telephone, and a telephone book. What time he did not spend cycling back and forth from a Vietnamese restaurant he spent lying in the grass in his backyard, or at the butterfly exhibit at the Memphis Zoo. He played at a beer joint called Barrister’s, quietly. He recorded sketches of new songs on Michael Bolton cassettes that he’d picked up for pennies and sent them to his band in New York. My Sweetheart, The Drunk tremulously came together. On May 29th, the band flew into Memphis to begin recording.

That night, Jeff sang Led Zeppelin as he waded into the river.

Kara VanderBijl is the managing editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Chicago. She tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about Call the Midwife.

with chrissie hynde

with chrissie hynde

"Ghost in the Room" - Numbers (mp3)

"Shortly Broken" - Numbers (mp3)

jeff buckley,

jeff buckley,  kara vanderbijl

kara vanderbijl