FICTION

FICTION In Which There Is Another Life Besides This One

Friday, November 29, 2013 at 10:16AM

Friday, November 29, 2013 at 10:16AM  by laura tryon jennings

by laura tryon jennings

Rocquefort

by MARK ARTURO

I saw my first painting by John Rocquefort when I was fifteen.

He was a friend of my father's brother David. My father was three years older, and the pride of his parents. Dad had inherited the family jewelry business and kept it solvent during very lean years. In contrast, David had been something of a wayward son, and the entire family seemed to view him with apprehension you show overly precocious children who never grow out of their eccentricities. There was also something darker there that I never completely understood.

They knew David owned a Rocquefort canvas — they kept it for him while he was away — but they did not know where he had procured it. David had spent the decade in the Orient until he came back in a coffin. The Orient was what my father called it, maybe because he had misunderstood a joke David told him, conceivably for other reasons. Unlike the rest of his family, my father did love David sort of effortlessly, the way a bird of prey encounters the air he had already moved beyond.

I too loved my uncle, but only in an absent fashion. Memories of him were hard to come by. Since he always wrote to me until he died, I assumed he wrote to my parents and many others that way.

I learned at David's funeral that this was not the case. None of the family had very much idea what David had been up to over the years. I told Dad some but not all of what David told me, as the letters hinted I should.

+

John Rocquefort arrived at the cemetery looking as a businessman might. He was a large man, towering over my entire family. He stuck out for this reason, and his presence there almost eclipsed the casket. It seemed to my aunt and my mother that his arrival had been both completely gauche and strangely relieving. David could not really have been so bad if this great man attended on him at death.

David went in the ground after that. I watched my father as the casket descended; slowly Dad's face was purloined of all affection, I remember thinking. When I think back on it, only one word centers in my mind to describe the entire affair: crass.

Rocquefort greeted all my relatives, introducing himself. They did not ask him to speak of David, and at the time I wondered why that might be — now I know it was because they were afraid of what he might say.

It was my father who made a show, at the reception, of offering Rocquefort his painting back. We all knew it was worth a substantial sum, and by the aghast expression on my mother's visage I knew she did not really want my father to do it. I saw Rocquefort, resplendent in the finest suit at the party, pause a moment. Others including myself centered our attention on his response. He shook my father's hand but did not take the painting. Instead he whispered a few words in my father's ear. My father nodded and Rocquefort excused himself.

Before I could ask either of my parents what had happened, my mother came over to me and explained that Rocquefort was waiting outside for me, and didn't he seem like a strange sort of tumbleweed? I did not have to go, she explained, but would I like to? You know what I said.

You also know the painting. It seems to open on a marsh. At first the greenish algae glimmering over the surface appears to extend roughly forever, but then it pulls back over the nose of an airplane, tumbling perspective itself askew. It is no marsh.

Outside, peeling back a rhododendron flower, Rocquefort shuffled a bit suspiciously. He loomed over me, though I was not short for my age, and had surpassed my mother's height when I was only ten years old. He stood nearly twice my size.

He did not move towards me, only asked if I knew who he was.

"Suppose I don't," I said.

"I was a friend of your uncle's," he said, ignoring my inflection. "I don't know what they - your family -" he choked. Then he seemed to stop at some new idea. I realized that he did not like them, and with that came the knowledge that I was not sure if I did, either. That insight too vanished with the wind.

He now looked, instead of brave and smiling, slightly corrupted. "What did they tell you of your uncle?"

I asked him quite sincerely by what right he felt he could ask me about my uncle. Instead of bristling, he smiled a bit wider and stood up.

"You're right, of course." I shuffled uncomfortably, but something crept into his eyes. I asked him how old he was.

"I'm 47," he said. "Well, that's what I tell people anyway. It's close enough. It must seem very old to you."

"I'm fifteen," I said, since I could think of nothing else, and had to fall back on fair play.

He twisted a flower in his hand and dropped it. "If you wish," he said brightly, "you may live with me, until you are 18, and then you may stay or do as you like." Blood rushed into my face. I leaned forward to capture some of the meaning I felt I must have missed in this sudden change of topic.

Rocquefort offered me a cigarette and I declined. I began to answer him with a question, and did not complete it. Out of respect, I made it a statement.

"You loved my uncle."

"Yes."

"Once he wrote me he was not sure."

Rocquefort sighed and said, "In every relationship, you understand, one person is more responsible for it than the other, if only by degrees." He suggested the cigarette again and I took the offering, holding it my hand. He said, "You're Jewish. Did you know?"

I asked if he was a Jew.

"Yes. My mother was. She was a wonderful woman. The only thing she loved more than God was me."

I asked if he missed David.

"He was my life. He reminded me of my mother, I'm not ashamed to say. I have always felt, you understand" — he said this often, I noticed, usually when he thought I was not really going to understand — "that something was missing in me. I learned it could not be filled, not really, only abrogated. But here I am telling you that life is full of concessions. You live in this place. You know."

You can probably imagine how difficult it was for me to wrap my mind around this. Finally I asked whether he had known my true mother. He nodded, and explained he had come here to tell me of her, and other things. "David did not want you to know. She was taken, along with other members of her family. She would have known you if she could." He made an expansive gesture I could not recognize.

"He longed to stay with you, you understand. You must know how much he wanted to take you with him, but he could not. They would have brought him back in chains." His face took on a wretched cast, and he turned away. I said I thought I understood, and that David had tried to tell me without telling me.

My father emerged from the house then, carrying Rocquefort's painting under his arm like a scolded child. "It belongs to you," Rocquefort whispered to me. He smelled airily of carnations, I have always remembered that as important. "It has always belonged to you. And many others do as well, no matter what you decide to do." I could see in my father's eyes that he thought the artist was telling the truth.

+

The next days passed uneventfully. My parents did not ask me what Rocquefort had spoken to me about, and they seemed glad he had not accepted their offer of his own painting. My life went on as before. I went to school, did my lessons, and nothing seemed very different, except there was suddenly the presence of another possible life parallel to my own that I might have been living all this time.

The fact that David was gone dimmed my anger at him leaving me for the second time. Mitigated, but not at all completely. In the interim, I sought out all I could find about Rocquefort in the local library. My mother saw me at this.

One night, as I rested my head against a pillow, I felt something hard and flat instead. It was a retrospective on an exhibition of Rocquefort's work entitled The Lantern Beyond the Ceiling. In those pages, the elements in his paintings were rendered if not comprehensible, then clearer. Each was far more individuated, and the curator of the exhibition explained the themes and relative movement in the man's evolution. Personal comments sometimes filtered in; she appeared to hold her subject in unbelievably high regard, but there was still considerable distance between them, as between a toad and a marsh, a soldier and his country, or a woman and her nightmares.

Naturally I reviewed the letters from David in a new light. Still, I did not feel I was uncovering very much, and I packed up. You know where I went.

The lavishness of his hotel surprised me, even though I had mentally prepared for what I believed I would see. Although I knew it was very far beyond the means of anyone I knew to live this way, I also sensed that John Rocquefort himself was not entirely comfortable in such places either.

Since that time, I have learned Jews believe this is an aspect of their existence that can never be removed or forgotten completely.

Seeing Rocquefort in robe and slippers, divested of the order David had described in his detailed, abstruse letters, relaxed me. I showed Rocquefort that I held David's words in my hands without saying anything. I placed them on the bed. They were not very painful to me, as I had read them too many times to be fearful of what they contained, but in case they upset him, I said, "You need not look at them at all."

The expression of surprise and pleasure on his face told me everything else I needed to know about him.

His house, in the south of France was magnificent. I stopped counting all the people he paid to get us there. When I could stand it, I was attended on by an ancient servant named Alexandros. There was a maid who prepared my bed and washed my clothes. Her name was Velma, and she had a daughter whose eyes were the deepest shade of green I had ever seen.

Since I had not taken any clothes with me, I had been prepared to wear my best blouse and pants for as long as I had to. Rocquefort, or someone he knew, seemed to know what I might be comfortable in. The weather there afforded me the luxury of wearing very little. He taught me himself from the first day I arrived. At the end of my first lesson, a survey of the troubadour civilization of the Languedocs, he asked me if I wished to write to the people who had, inescapably, raised me.

I said I thought they knew, if not exactly where I was, then where I had been going. I told him I did not see the point of saying any more.

After a month of getting fat and slim again by swimming in the ocean, Rocquefort packed me away in his car on a random Tuesday. I supposed we were going to his dealer, a tiny man named Jerome, or to his friend Elaine who lived a few miles away as a happy widow.

Instead we arrived at a bustling, impossible building in the heart of Marseille.

The sun hit David at a distance, any distance, alongside a magnificent locomotive. It seems completely silly then and now, but watching him come into view, I felt so thankful for progress, for whatever engines had brought my true father to me. Advancement was marvelous, at heart, and those who disapproved of it were nothing more than detritus. The world, the old world that was, would still be there if I wanted it, though I did not. I hoped it was lost.

Mark Arturo is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is a writer living in Brooklyn. He last wrote in these pages about the run of the play. You can find an archive of his writing on This Recording here.

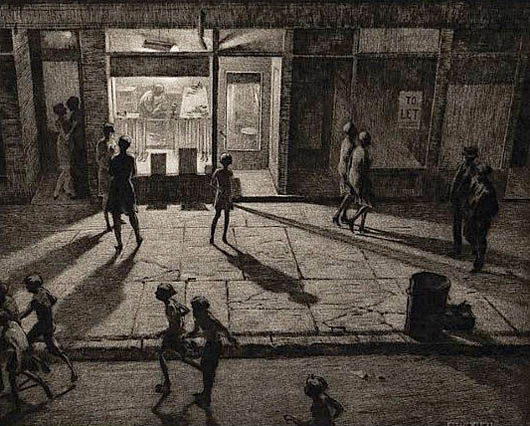

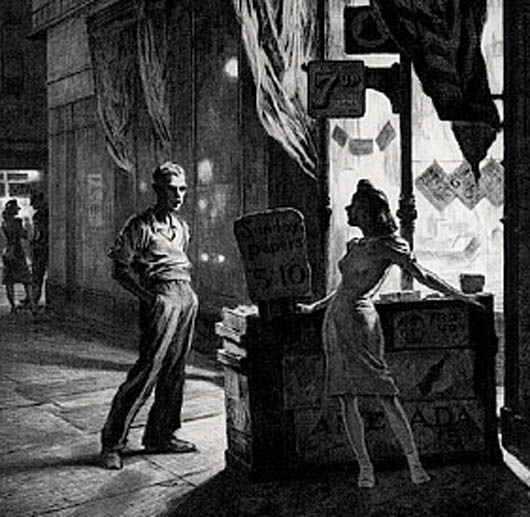

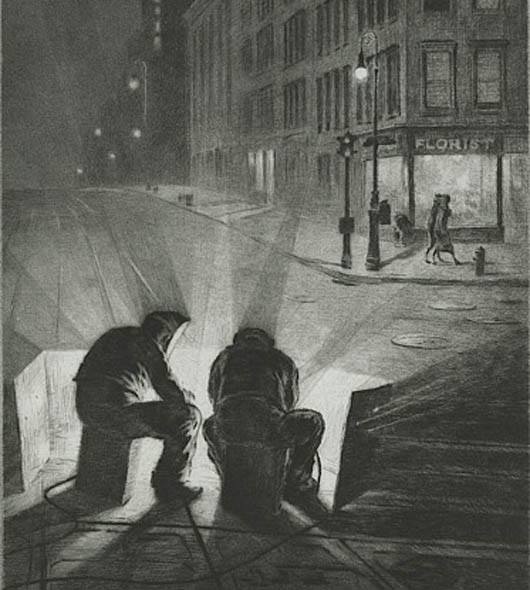

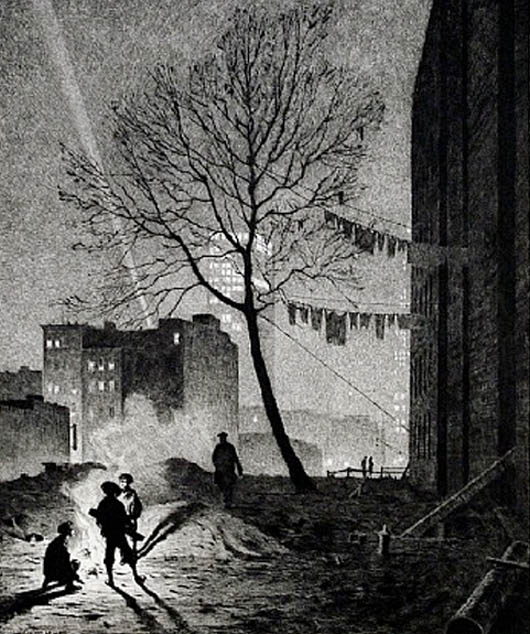

photograph by Aleksandra Mir

photograph by Aleksandra Mir

"Let Her Go" - Jasmine Thompson (mp3)

"Stay" - Jasmine Thompson (mp3)

languedoc,

languedoc,  mark arturo

mark arturo