Our Novels, Ourselves

This Thursday, This Recording unveils our list of the 100 Greatest Novels. This will likely be the final word on the subject, and a key to the city will be presented to us in the shape of a novel. In order to broaden our horizons, we asked a group of talented young writers and artists to name their favorite novels. This is the first in a three part series.

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Elisabeth Donnelly, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)

Tess Lynch

In the Lake of the Woods by Tim O'Brien

This is a book about Vietnam. Please, sit down. Come on, it isn't really about Vietnam, it's about – just sit down for one second – the clashing of public and private life, when the demon-like personifications of every horrible thing you've ever done wage war with whatever good parts of you still exist; the plot consciously implodes on itself, leaving you feeling psychologically fractured and with nightmares about killing your houseplants with boiling water while screaming "Kill Jesus," just like you've always wanted.

Chilly Scenes of Winter by Ann Beattie

Ignore the movie please. This was Beattie's first novel, and my favorite of hers, not only because there's a character in it who spends all of her time in the bathtub like I do, and not only because Sam is the fictional hot best friend I projected any and all fantasies onto during my formative years, but because it's a quiet study of the electrically-charged feeling of being in love operative-word-hopelessly. The desserts she cooked that you miss, the radio songs, the happy hour beers spent bumming. Too true, Ann, too true.

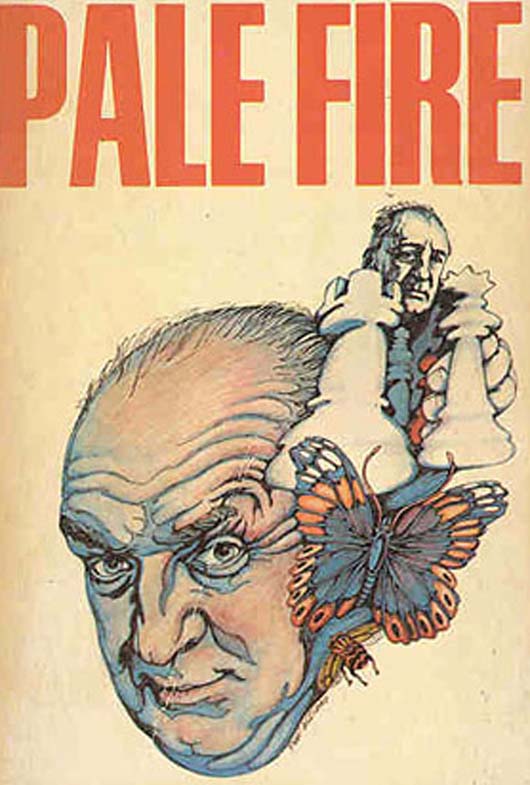

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

You know what? Fuck Lolita. I take that back, don't fuck Lolita, she's too young, plus I loved that book. I loved this one more, though. The poem makes me disintegrate with feelings. I'd get all 999 lines tattooed on my face, but then I'd never be able to work in corporate America. John Shade's poem can be a bit of a downer ("how many more/Free calendars shall grace the kitchen door?"), so fictional editor Charles Kinbote comes in to offer up some zippy commentary from the imaginary land of Zembla. I thought Kinbote was supposed to make me feel better, that that was his purpose, but apparently Nabokov, in an interview, mentioned that Kinbote killed himself after publishing the manuscript. God, what a downer. I wish I'd never heard that bit of imaginary news; maybe there's no point to anything and I should go ahead and get that tat, do you think it would be pretty sickkk?

The Stand by Stephen King

This is my favorite Stephen King novel, and that's saying a lot, since I never leave the bookstore without some SK representation. The Stand is so long that if you get the uncut edition, you can step up onto it and get the bird's nests off your roof; even still, you feel depressed when you turn the last page. There's nothing like a story that begins with the end of most of humanity and then continues for about 1100 pages, peppered with the lyrically satisfying name Trashcan Man and lots of details about stomachs exploding. Life is gross. Books can be gross. You didn't want to finish those nachos anyway.

Tess Lynch is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Karina Wolf

Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin

These days, Melmoth the Wanderer is more an allusion than a perused text. Nabokov named Humbert Humbert’s automobile after the damned nomad; Oscar Wilde took "Melmoth" as a pseudonym, perhaps because of his shared status as eternal outsider. Maturin’s 1820 gothic novel begins with a bequest – a young Trinity student inherits his uncle’s estate and a manuscript, which relates the tale of his ancestor Melmoth, who extended his life by 150 years, presumably by selling his soul to the Devil. The only out from damnation is to find someone to take over the pact. The novel consists of a rococo series of nested vignettes, wherein characters encounter the cursed wanderer, sometimes peripherally. The pleasure (and challenge) of the text is in its stylish excesses.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

I re-visited Wuthering Heights when I taught at hokwan, a Korean cram school that aimed to stuff as many five dollar words possible into the minds of the foreign-born students. The odd task of reading Brontë’s novel aloud to a teenage boy (who loved it) made me appreciate its ingenious storytelling along with its elemental feelings. As a child, Brontë endured the deaths of two sisters and in response created Gondal, a detailed imaginary world that she sustained in letters and stories from adolescence to adulthood. Wuthering Heights retains a similarly corrective power; the novel is less a romance than a psychic outcry and self-assertion.

The Witches by Roald Dahl

The best children’s books are clever rejoinders to the early onset of life, primers for how to deal. Roald Dahl’s The Witches retains the violent menace of early fairy tales while offering readers a wry (and controversial) antidote to vanquishing the enemy, a kind of mass witch transformation and cat-led genocide. Dahl retains his spiky humor and incorrectness – also, his irresistibly charming prose. With lovely line drawings by Quentin Blake.

Karina Wolf is a writer living in New York. Her book The Insomniacs is forthcoming from Penguin. You can find her website here.

Elizabeth Gumport

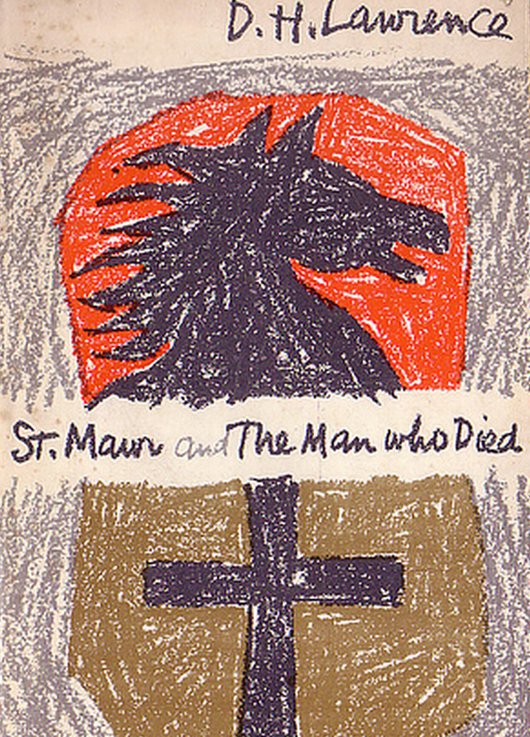

I am too adrift from myself to know what my favorite novels are. If I could tell you that, I could tell you so many things! But like rats fleeing a sinking ship, my former selves keep escaping me. One of the few things I am sure of these days is that I am twenty-five years old, and so like a child I go around insisting on my age. But we can forgive a child for identifying herself by how old she is, since what else would she have done with those months and years except live them? I, on the other hand, ought to have more and deeper moorings. Instead, the first page of D.H. Lawrence’s St. Mawr looks like a mirror: "Lou Witt had had her own way so long, that by the age of twenty-five she didn't know where she was. Having one's own way landed one completely at sea."

Reading St. Mawr, the feeling I had was not of identifying with the character but of being identified by them. I did not “find”myself. I was found, as if by a carrier pigeon bearing a note. A few months later, it was The Wings of the Dove that saw me: James writes that Kate Croy “had reached a great age for it quite seemed to her that at twenty-five it was late to reconsider, and her most general sense was a shade of regret that she hadn't known earlier. The world was different--whether for worse or for better – from her rudimentary readings, and it gave her the feeling of a wasted past. If she had only known sooner she might have arranged herself more to meet it.”

My sense of being “found”by these books was heightened by how I happened to read them: St. Mawr did in fact arrive for me by air, in a package from Amazon. It was a gift from a friend – the same friend who several months later would be the one to recommend The Wings of the Dove. A truly personal recommendation shows you something you don't often see, which is the way you hold yourself out to the world. That is what Lord Mark offers Milly Theale in The Wings of the Dove, when he shows her “the beautiful” Bronzino portrait “that’s so like” her. What matters is not merely what you are like, but that you are like something – that the world knows what you look like, even when you don’t. When shown the portrait, Milly admits she doesn’t see the resemblance.

Knowing that a book exists is one thing, being made to recognize its existence by someone else another. It is the fact of Lord Mark’s showing her the portrait, and not the portrait itself, that so topples Milly: “It was perhaps as a good a moment as she should have with any one, or have in any connexion whatever.”A personal recommendation is not the same as one cast out to anonymous strangers on the internet.

I will try, therefore, to be as specific as possible: if you are my age, self-absorbed, and aimless but not hopeless, you should read these books immediately. Perhaps the figure sketched in them will impress you as your own, and perhaps it will resolve something for you. Sometimes books enter your life at exactly the right moment. It doesn't happen as often as you'd think: like people, they tend to appear too early, when you are too foolish to appreciate them, or too late, when they have been claimed by someone else.

Elizabeth Gumport is a writer living in New York.

Isaac Scarborough

Tigana by Guy Gavriel Kay

Amongst all of the fantasy novels I devoured as an adolescent, Tigana is the only that holds up through the prism of passed years and moderate maturity – going back and rereading it remains the same mind-bending pleasure that it was when I was fifteen. Not only is it – a rarity in the subgenre – genuinely well written, but it does what fantastical writing is truly meant to: it comments on our world today, in a way that would otherwise be impossible. The power of names and naming stuck with me, and if there’s a reason why I today refuse to spell Ashkhabad “Ashgabat” Kay may very well have something to do with it.

Making Scenes by Adrienne Eisen

The basic willingness to describe modern life’s brutality – from lists of food consumed and bulimiacally purged, to the absurdity of what passes today for courtship – sets Eisen apart; her willingness to describe without going somewhere is also laudable. Reading Making Scenes is an experience closest to voyeuristically watching that cute neighbor across the hallway, except that she has begun to leave audiotapes on your doorstep of her – just as you suspected – far too aware and intelligent inner monologue. This voice sticks around.

Demons by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

By and large, Dostoyevsky doesn’t do plot: throughout his works, there are simply long periods of hysterics and contemplation, generally circling around a heinous crime committed in the very beginning of the work. Demons is no different in this respect, but here the hysterics come first, and then the crimes – a set-up that avoids the disappointment with which both Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment end, and one that provides much more space for the author to develop his characters’ private insanities. And when it comes to madness, Dostoyevsky simply has no equivalent.

Isaac Scarborough is a writer living in Kazakhstan.

Sarah LaBrie

The Quick and the Dead by Joy Williams

A manifesto for young women destined to spend adulthood in a dimension just to the left of reality, the result of not having solidified quite correctly as children. The three teenaged orphans who guide us through Williams’ strange desert are peculiar but not precious, compelling in their very anti-Amelieness. It’s okay to be a genuine girl wacko, Williams tells us: if you’re smart enough to own it, you still get to win.

Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson

Fiction writers who start out as poets have an edge when it comes to building faultless sentences. Carson, a Classicist by trade, applies her skills as a translator of Greek verse to a novel about a monster named Geryon and his arrogant sometimes-boyfriend, Herakles. Building loosely on fragments of a poem by Stesichorus, Carson winds together scholarship and brutal wit to build a discomfitingly relatable love story.

The Counterlife by Philip Roth

In the autobiographical note that begins Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin discusses coming to the conclusion that, before he could produce anything else of substance, he had to write about what it meant to be black. Through the lens of Nathan Zuckerman, Roth offers a metafictional take on the same question as it relates to Judaism while experimenting with perspective, structure, time and form. Probably the most skillfully written examination out there on the bond between fiction writing and the desire for control.

Sarah LaBrie is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Daniel D'Addario

England, England by Julian Barnes

In college, one of my mistakes was taking a class on comparative literature, after which I was left thinking that Britain or America could never produce a homegrown “national allegory.” Was I ever wrong! England’s image of itself is grist for this bizarre novel of ideas in which the nation is reassembled as a giant theme park for tourists—with a false king and queen and every famous Briton brought back to life. The novel questions the value of history and of myth—and despite its scorched-earth ending and brilliant dissection of the corporate profit motive, it does so with a bit of affection.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan

Including Kazuo Ishiguro’s cloistered-England novel The Remains of the Day in my three favorites here felt a little unfair; it’s like being asked to choose among your children, when one is an ultra-sensitive genius. Instead I chose to include the instance in which Ian McEwan, predominantly a creator of tight narrative schemes, most closely approaches Ishiguro’s sensitivity to context (a past era’s very Britishness) and to character. For not the first but the most exhilarating time, McEwan’s games have real consequence: the fate of a young marriage.

Morvern Callar by Alan Warner

Novels with inert protagonists slay me, like Mary Gaitskill’s books, or Updike’s Rabbit series: watching things happen around characters is somehow more exciting and lifelike than watching characters conquer situations themselves (with the author’s help). The protagonist, the amoral Scottish girl Morvern, is glamorously inert; things happen around her as she observes and calculates. The scene in which Morvern, unmoved, lights a Silk Cut cigarette while staring at her boyfriend’s corpse is choked with an ennui Camus would envy.

Daniel D'Addario is a writer for The New York Observer. You can find his website here.

Elisabeth Donnelly

Another Bullshit Night in Suck City by Nick Flynn

Nick Flynn was a poet, and a good one, before he was a memoirist (shades of Denis Johnson), which is why his raw recounting of a fragile family stings with moments of sharp beauty and heartbreaking empathy. The plotline is relatively simple; when Flynn was 27 and working at the Pine Street Inn, a homeless shelter in Boston, he comes into contact with his long lost father. The book is elliptical and non-linear, echoing Flynn’s memory, diving into blood and family legacy, Flynn’s father’s delusions of grandeur and his mother’s suicide, homelessness, forgotten people, the way cities and vice can chew you up, and the burden of the past on Flynn’s own life. It will knock you on your ass.

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

The thing that sticks in my mind about Ralph Ellison’s masterpiece is that it’s so… weird. The imagery that he uses to describe the cruelty of this world is unforgettable: the nameless protagonist in his basement with 1,369 lightbulbs, the Black youths forced to fight for gold coins on an electrocuted rug, the riot (and spear) that rips through Harlem thanks to the Invisible Man’s gift of speech. While the book is ostensibly a record of growing up Black in a divided America, Ellison defies expectations at every turn, putting his character through scenes that are consistently strange and always feeling new (which left a legacy extending from John Cheever’s short stories to Paul Beatty’s The White Boy Shuffle); and this surprise means that Ellison can cut sharply with the anger, satire, and moody magnificence that’s fueling his work.

The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy

In the category of smart-girl-coming-of-age novels, Elaine Dundy’s American girl in Paris farce is particularly delicious. You’re in good hands with Dundy, after all, her biography was called Life Itself! (yes, with the exclamation point). The semi-autobiographical adventures of Sally Jay Gorce follow her as she dates, fucks, quips, and somehow makes a bad art film in the French countryside. It’s hilarious, and by the story’s end, proto-feminist Sally Jay is like a friend you don’t want to leave.

Elisabeth Donnelly is a writer living in New York. You can find her website here.

Lydia Brotherton

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

I was late to the Brideshead party – I only read it a couple years ago — but now I’m one of those people who owns the entire Granada miniseries and sort of goes on about gillyflowers and plover’s eggs too much. I can’t help it, and I’m not sure I can explain it without embarrassing myself: I really love this novel.

Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf

When I first read Orlando, I was confused by its weirdness and delighted by its casually historical imaginings (there is absolutely no way to read fiction involving Elizabeth I that isn’t tacky except for this). And although I haven’t reread it in a while, I remember and misremember it like a tricky, particularly good dream. Maybe if there were an umami taste of novels, Orlando would be it.

Chéri by Colette

One of the reasons I like reading Colette novels is that in addition to being evocative of summer holidays in France I’ve never had, they have the potential to read as little lyrical self-help books. To be honest, what actually happens in Chéri is less important than the life lessons I manage to project onto all that description of pale, beribboned wrists and afternoon weather: how to wear silk robes during the day and take up with younger men, why it’s nice to upholster your furniture in dove-gray velvet, and — maybe most importantly—how to grow older, and, in your increasing age, more glamorous, demanding.

Lydia Brotherton is a soprano living in Basel, Switzerland. You can find her website here.

Brian DeLeeuw

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

"Favorite novels" is a slippery idea. Favorite when? When I read it? Now, years later, in the memory of reading? I’m not sure I would even finish Danielewski’s novel today (this is saying something bad about me, not the novel), but its blending of pulpy horror and deconstructionist theory felt custom designed for where my head was at ten years ago, in the middle of college. I’ve never in my life been as consumed by the experience of reading a book. Probably I should try to read it again.

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

One of the ways a satire can be judged successful is if a lot of people don’t understand that it’s satire. Another is if a lot of these same people get very exercised and moved to protest and write angry and self-righteous ad hominem reviews. American Psycho passes both tests. If there remain any doubters (after talking to some of my friends, I know they’re out there), the fact that Mary Harron directed the movie adaptation should be proof enough. This is the funniest book I’ve ever read, which makes it puzzling why much of Ellis’s other work is so unfunny and sometimes plain bad.

Veronica by Mary Gaitskill

Mary Gaitskill writes about complicated and uncomfortable emotional states with more precision and cold elegance than anybody else I have read. She’s most known for doing this in her short stories, and in some structural ways Veronica feels like a very long story rather than a novel. But those sort of classifications are irrelevant here. The book spares no one, least of all the reader. The prose itself is a representation of one of the novel’s central ideas: beauty is cruel, but no less beautiful because of it.

Brian DeLeeuw is a writer living in New York. He is the associate editor of Tin House and the author of the novel In This Way I Was Saved. You can find his website here.

Our Novels, Ourselves

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Elisabeth Donnelly, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)

The 100 Greatest Novels

If You're Not Reading You Should Be Writing And Vice Versa, Here Is How

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

FILM

FILM  Friday, April 22, 2011 at 10:39AM

Friday, April 22, 2011 at 10:39AM

Quentin Dupieux’s Rubber is a movie about a psychokinetic tire that kills people with its mind. We know the tire — listed in the credits as “Robert” — is about to blow someone up when his rubber tubing vibrates and the film score swells. This happens mostly when people stop Robert from doing the things he likes to do, like taking a shower, or watching television or stalking a beautiful French girl named Sheila. After he wipes out a California desert town, Robert is shot to death by the police and comes back to life as a tricycle. Tricycle Robert advances on Hollywood, an army of reanimated tires in his wake.

Quentin Dupieux’s Rubber is a movie about a psychokinetic tire that kills people with its mind. We know the tire — listed in the credits as “Robert” — is about to blow someone up when his rubber tubing vibrates and the film score swells. This happens mostly when people stop Robert from doing the things he likes to do, like taking a shower, or watching television or stalking a beautiful French girl named Sheila. After he wipes out a California desert town, Robert is shot to death by the police and comes back to life as a tricycle. Tricycle Robert advances on Hollywood, an army of reanimated tires in his wake.

quentin dupieux,

quentin dupieux,  rubber,

rubber,  sarah labrie

sarah labrie