SEX

SEX In Which It Is Now In Harsh Color

Thursday, January 30, 2014 at 11:54AM

Thursday, January 30, 2014 at 11:54AM

Office Hours

by JULIA CLARKE

"How shockable are you?" he asked. I was seated in my professor's office one winter day, sipping black coffee and discussing the prospect of graduate school. In the English department, at least at my alma mater, meeting with a professor for a chat is not unusual; in fact, it's recommended, especially if you're considering a PhD in English. Having a mentor who knows you well can be the key to admission, but it also assuages the agony of working toward a career in the humanities, a field that is notoriously overlooked and underfunded, especially in a lackluster economy.

That day, the conversation shifted from standard evaluations of choice programs to literature in general to something personal — something dark and secret — that I wasn't sure I wanted to hear. Was I shockable? Since starting college, with its STDs, keg stands, and recreational drugs just a house party away, I liked to tell people that nothing shocked me anymore, but then again, I was only 20 and privately knew better.

"Um, I don't know," I stammered. It was one of those moments — flashbulb memories, psychologists call them — that you recall with piercing vividness because of its inevitable impact on your life. The wise, clean-cut and closed-off professor, clad in tweed and lecturing from the Bible despite departmental taboos, was about to expose his worst weakness.

"I had a relationship with a student that lasted two years," he said calmly. It ended in 2004. She was his assistant and about 40 years his junior, a girl who already had a boyfriend her own age but who somehow felt compelled to sleep with a married man technically old enough to be her grandfather.

In my attempts to be well-liked, to be thought of as free, open-minded, and most importantly, an intellectual, I told myself it was perfectly natural for an elderly professor to seduce a student. Words are inflammatory, and they shared a passion for literature. It's the age-old university tale: I wasn't really a fan of it, but I got it.

Shortly after his confession, he pulled out an envelope tucked behind some papers in a file cabinet. "Let's just — close this door—" he said, gently pulling the entry door shut, and then in the quiet seclusion of his immaculate office, cluttered his desk with pictures of her so that I could place a face to a name.

No longer was his affair something nostalgically and distantly described, as if read from Nabokov: It was now in harsh color, with youthful brown hair and friendly eyes, staring back at me. It wasn't just one, either. He sifted through the envelope's contents with a practiced hand, dropping photograph after photograph of women he slept with starting in 1966, when he earned his PhD. He was no longer the distinguished research professor I admired but instead a crusty Casanova, boasting to a friend his sordid parade of conquests.

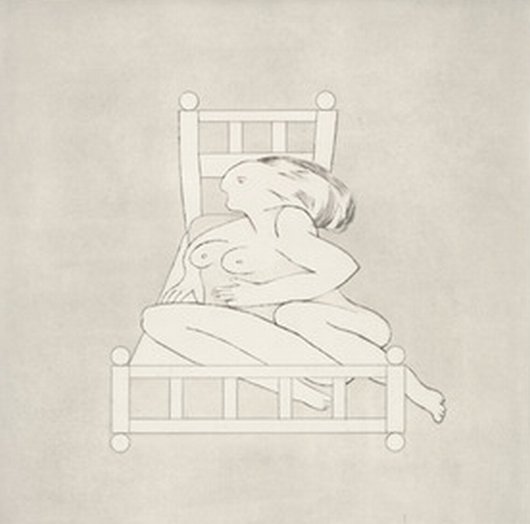

Girls were captured smiling and windswept; others were serious, with crossed ankles and austere faces; one posed nude. They were all beautiful. Out of all the images, though, the one that disturbed me the most featured a dark-haired student, one of his favorite affairs, in the 1990s. She was photographed on a nondescript couch, her thin legs comfortably tucked behind her, intently reading a book. Seeing her like that — so casual, so young, so unaware of the camera’s invasive gaze — made me queasy. He told me they hadn't spoken for years, and I wondered if she still thought of him, if she regretted the affair, and how hard it was to overcome its demise.

He was her first lover — he shared that with revolting pride — and I considered how damaging that is to young college student. What's it like to have your first real romance be someone who so easily overpowered you with age, postgraduate degrees, and published books, not to mention the morbid promise of an end? "I'm married for life," he said, pointing a fat finger at his gold ring, but it felt like mockery, to the students he slept with and to his wife who bore him children. What is marriage if not fidelity?

I have been told more than once that I have uncanny composure, seldom revealing my real feelings. Keep calm and carry on, Her Majesty says, and I make it my mantra. In this case, though, as I flipped through pictures of women who seemed normal, happy, and most profoundly, young — too young to be in bed with a man well into the autumn of life — I still have no idea what my face looked like. "Are you okay?" he asked, to which I replied coolly, "Yep, I'm fine." "You're always fine," he said darkly, and I'm sure I reddened.

We didn't talk much more about his past lovers after that; the photographs and accompanying histories were something I blocked from my immediate consciousness, turning instead to enlightening discussions about literature, God, his sickly mother, his grandchildren and children, art, music, Paris, England. We met regularly, my black coffee always patiently waiting on the other side of his desk, and we e-mailed too.

He taught me literature so well and so easily that I refused to see him for what he was, a man with authority who took advantage of his impressionable students. Instead, he was an accomplished savant who surprisingly respected me despite the department's jaded tendencies. He might be weird, but nobody would deny he was both bright and prolific, and he treated me as an intellectual equal. "I must tell you that your e-mails are beautifully literate," he wrote once in February. I was flattered.

In the midst of our meetings and correspondence, I was writing a paper on King Lear, and I wondered if he were my own King Lear, mystically transported from Shakespeare's ancient England to Florida's muggy reality. Like Lear, my professor was a tired old man seeking an outlet — a cold and non-discriminating heath — for his past transgressions, so that he could, as Shakespeare penned, "unburdened, crawl toward death." Maybe this relationship, however strange, was happening to me so that I could understand aging better, or at the very least so that I could write a good paper on a play that troubled me above all the others.

Once, King Lear came up in conversation, specifically the scene where Lear announces he'll give the most generous slice of his kingdom to the daughter who loves him most. Cordelia, Lear's favorite, professes she loves him only "according to her bond," and her honesty sends Lear into a maddened rage.

"Should Cordelia really have been honest with poor old King Lear?" my professor asked, but he swiftly answered for me, "Lear did not want the truth — he wanted kindness." Was that valid? When life has harried him for several decades, was there a point where I should just accept bad behavior and indeed, commend it with kindness, just because he lasted this long?

My professor needed an understanding and silent ear, someone who wouldn't tell him what was true but instead serve as his bucket, swallowing his past and assuring him it was all okay with my modest shrugs and slow nods. "I hope you enjoy keeping this secret as much as I do," he told me once, no doubt fearful I would broadcast his confessions. It made me feel strong, set apart even: I wasn't connected to it; I was containing it.

But then, ineluctably, he tried sucking me into his queue of sad affairs, gradually at first and later with aggressive insistence, sending me erotic poetry in e-mails, telling me I was lovely in the warm sunlight where we sometimes met to talk, comparing me to his past lovers. He even requested — jokingly? — a picture of me in a swimsuit to add to his ignoble envelope. "You are quite the embodiment of springtime," he wrote.

I ignored all of it, mechanically and with tenacity. He admired my clean refusal to acknowledge his compliments and trespasses. "You are a very wise — instinctively wise — woman," he said, but he was relentless. When he told me he loved me, I finally demanded that he stop. "I was hurt by your e-mail," he said, and his vulnerability sickened me. Correspondence puttered on for a brief time after that, although it was now jagged and noticeably tense.

In June, I traveled to Washington to celebrate my 21st birthday with my sister. "Let me hear from you when you get back," he wrote. Maybe it was that I was now 21 — too old and also too young to deal with his messy inner life — but reading that sentence laden with pathetic desperation, I knew that I couldn't talk to him anymore. I sent a terse response, abruptly ending communication.

Years later, I still don't know what the point of it all was. I count myself lucky that nothing physical ever happened (not even a handshake, he once pointed out) but his leers and his poetry were nearly as disruptive. Literature, my first real love, suddenly felt murky and uncomfortable, with its varying justifications for any and all action. I desperately wanted to see, in print, that some things really are right and wrong, but I was tirelessly left heartbroken.

I often thought about the girls he did manage to sleep with, particularly the one reading in the photograph. I'm sure that like me, she was blinded by his glittering analyses of art and text, and her self-doubts, like mine, were overshadowed by his crafty adulations. She just paid a higher price. Without his frequent affirmations, my insecurities returned, and the worst question of all came rushing forth: Was he complimentary because he wanted to bed us, or did he really think we were smart?

But time heals most wounds, or at least makes us forget the worst parts. I still wrote my honors thesis, still graduated, and still devour and study the literature I've always adored. Now, hundreds of miles from my college campus, I live and work in a city where I sometimes see short, mustached men in scholarly blazers, and I shudder, thinking it's him. It never is.

Julia Clarke is a contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. This is her first appearance in these pages. Paintings by Joan Brown.

"In The Same Room" - Julia Holter (mp3)

"Four Gardens" - Julia Holter (mp3)

julia clarke,

julia clarke,  king lear,

king lear,  sex

sex