ART

ART « In Which We Appreciate The Genius Michelangelo »

Wednesday, October 7, 2009 at 12:28PM

Wednesday, October 7, 2009 at 12:28PM

The Chisels and the Mallet

by PAUL JOHNSON

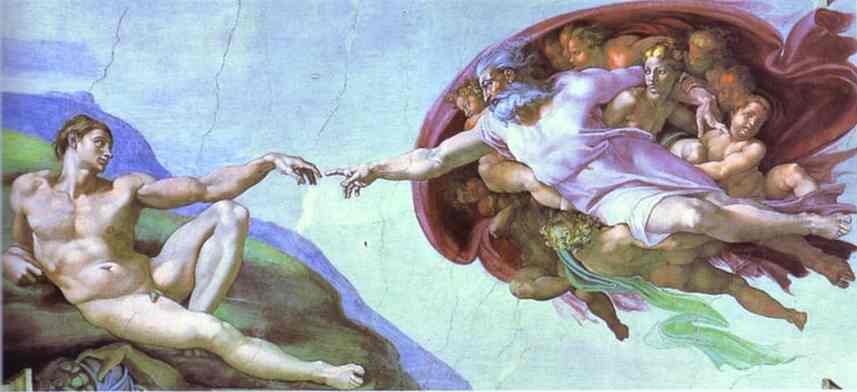

Michelangelo was primarily a sculptor, though it is probably true to say that he was more interested in the human form as such than in any particular way or medium in which to represent it. Obviously he found carving the best way of doing it, and his paintings tend to be two-dimensional sculptures. His wet nurse was a stone-carver's wife from Settignano, and Michelangelo told Vasari that "he sucked in the chisels and mallet" with her milk. His father was an ambitious, social-climbing bourgeosie of Florence, who kept Michelangelo at school until he was thirteen and was most reluctant to allow him to sculpt for a living, believing it to be manual work and demeaning.

This may explain why the boy was first apprenticed to a painter, Domenico Ghirlandaio, in 1488. Only in the following year did he manage to get himself into the sculpture garden workshop in the Medici House at San Marco. He taught himself by copying the head of an antique faun, which attracted the attention of Lorenzo "the Magnificent."

Michelango was made when, at seventeen, he produced his first masterpiece, a marble relief, The Battle of the Centaurs. It is an exciting work, done with great facility and striking economy, the nude male figures exhibiting extraordinary energy in punching the narrative home to the viewer. But is unfinished, for reasons we do not know, and this became almost the hallmark of Michelangelo's work. However, he did finish his first important comission, a Pieta (Mary with the dead Christ) intended for the tomb of a French cardinal in Rome. Michaelangelo began it when he was twenty-two and completed the project to a high state of polish three years later. It is by any standard a mature an majestic work, combining strength (the Virgin) and pathos (the Christ), nobility and tenderness, a consciousness of human fragility and a countervailing human endurance, which fill those who study it with a powerful mixture of emotions.

It is the ideal religious work, inducing reverence, gratitude, sorrow and prayer. The standard of carving, of both the flesh and the draperies, is without precedent in human history, and it is not hard to imagine the astonishment and respect it produced among both cognoscenti and ordinary men and women alike. The youth of the sculptor made him a wonder, and the acclaim given to the work was the beginning of Michelangelo's reputation as an artistic superman, larger than life — like some of his works — and endowed with godly qualities.

Whether it benefits an artist to have this kind of reputation is debatable. Early in the sixteenth century, Michelangelo created from a gigantic marble block that had already been scratched at by earlier artists a heroic figure of David, designed to stand in the open (it is now in the Accademia, Florence) and overawe the Florentines. He omitted Goliath's head and the boy's sword, and the enormous work is a frightening statement of nude male power, carved with almost atrocious skill and energy. It made both Donatello's and Verrocchio's depictions seem insignificant by comparison, and it added to the growing legend of Michelangelo's supranormal powers, patrons and public alike confusing the gigantism of the work with the man who made it.

The year after he finished it, Julius II summoned him to Rome to create, for his own vanity and the admiration of posterity, a splendid marble tomb with a multiplicity of figures and a magnificent architectural setting. Michelangelo accepted with joy the chance to create such an ambitious work for a munificent patron, and he did indeed complete, to his satisfaction and everyone else's, at the time and since, part of the whole, a superb Moses, the godlike image of the law figure and judge who is the central figure in the Old Testament.

Many would say it is the sculptor's finest work. But the entire project took forty years and was never finished as intended. It involved the artist in quarrels with the great, flights from Rome, lawsuits and endless anxiety, even a sense of failure. It destabilized Michelangelo as a man and an artist, and affected his attitude to work that had nothing to do with the tomb.

In the Accademia, Florence, there is a partial figure of the Atlas Slave for the tomb, really the torso and legs alone, the rest of the marble being cut to size but unworked. Why was it abandoned? We do not know. The Dying Slave, also intended for the tomb, has the figure complete, and magnificent it is, but the supporting back and base are only roughly worked. Why? We do not know. Two marble tondos of the Virgin and Child are also incomplete, the superb faces and limbs emerging tentatively out of rough working. Time and again, Michelangelo conceived a grand or beautiful design, roughed it out, worked at it, completed part, and left the rest, whether from lack of time, pressure of other commissions, dissatisfaction with his work or sheer exhaustion is rarely evident.

In the Accademia, Florence, there is a partial figure of the Atlas Slave for the tomb, really the torso and legs alone, the rest of the marble being cut to size but unworked. Why was it abandoned? We do not know. The Dying Slave, also intended for the tomb, has the figure complete, and magnificent it is, but the supporting back and base are only roughly worked. Why? We do not know. Two marble tondos of the Virgin and Child are also incomplete, the superb faces and limbs emerging tentatively out of rough working. Time and again, Michelangelo conceived a grand or beautiful design, roughed it out, worked at it, completed part, and left the rest, whether from lack of time, pressure of other commissions, dissatisfaction with his work or sheer exhaustion is rarely evident.

Of course great artists sometimes prefer their work to be unfinished: it gives an impression of spontaneity and inspiration that a meticulous veneer obscures. But in some cases, as in the great tomb of the Medici, with its awesome figure of the seated, pensive Lorenzo, itself complete as are the two supporting nudes beneath, niches are left empty and an air of incompleteness hovers over the whole.

Did Michelangelo suffer from some sickness of the soul? He was quarrelsome and often angry with himself as well as others. He seems to us an insolated figure, isolated in his greatness, in his lack of a private life or privacy, his heart empty of consummated love, his only competitor and measuring mark the Deity himself.

Paul Johnson is a historian living in Great Britain. In 2006, he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This excerpt is taken from his book The Renaissance, which you can buy here.

"It's Not So Hard" — Sparklehorse (mp3)

"Knives of Summertime" — Sparklehorse (mp3) highly recommended

"See the Light" — Sparklehorse (mp3)

michelangelo,

michelangelo,  ppaul johnson

ppaul johnson

Reader Comments (2)

I very much enjoyed this (having once lived in Florence), and it reminded me of something my teacher remarked when we were studying his unfinished works. He asserted that Michelangelo had too many lives worth of ambitions inside of him. He couldn't have lived long enough to complete any of his grand and exhaustive artistic plans, and this has always left me feeling as though he was feverish or blinded in his love of pursuing the perfected form. I also recall reading that he was incredibly reluctant to paint in the sistine chapel because it deterred him from his sculptural endeavors. I lived down the street from L'Academia when I was studying abroad, what a brilliant place. The unfinished works appear to be tearing themselves free of the marble. Its just brilliant.

it's nice contribution towards the artistic appreciation of the work of Micheiaengelo