BOOKS

BOOKS « In Which We Ride The Long Crooked Straight With Samuel Beckett »

Sunday, November 29, 2009 at 11:22AM

Sunday, November 29, 2009 at 11:22AM

Geworfenheit

by J.M. COETZEE

Although Watt, written in English during the war years but published only in 1953, is a substantial presence in the Beckett canon, it can fairly be said that Beckett did not find himself as a writer until he switched to French and, in particular, until the years 1947-51, when in one of the great creative outpourings of modern times he wrote the prose fictions Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable ("the trilogy"), the play Waiting for Godot, and the thirteen Texts for Nothing.

These major works were preceded by four stories, also written in French, about one of which, "First Love," Beckett had his doubt. (He might also have queried the ending of "The End": usually a master of restraint, Beckett indulges here in an uncharacteristic dip into plangency.)

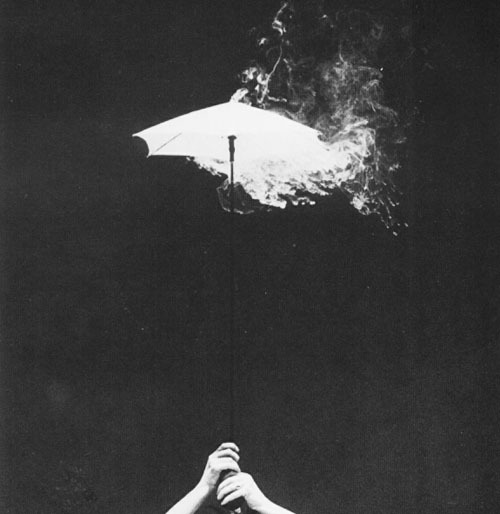

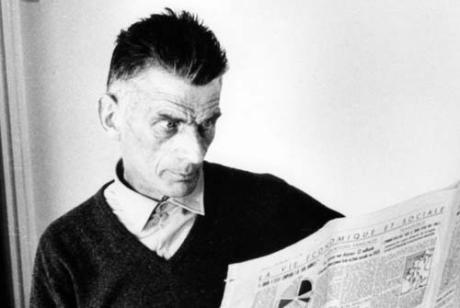

beckett and buster keatonIn these stories, in the novel Mercier and Camier (written in French in 1946) and in Watt, the outlines of the late-Beckettian world, and the procedures of Beckettian fiction generation, begin to become visible. It is a world of confined spaces or else bleak wastes, inhabited by asocial and indeed misanthropic monologuers helpless to terminate their monologue, tramps with failing bodies and never-sleeping minds condemned to a purgatorial treadmill on which they rehearse again and again the great themes of Western philosophy; and all of it will be presented in the distinctive prose that Beckett, using French models in the main, although with Jonathan Swift whispering ghostly in his ear, was in the process of perfecting for himself, lyrical and mordant in equal measures.

beckett and buster keatonIn these stories, in the novel Mercier and Camier (written in French in 1946) and in Watt, the outlines of the late-Beckettian world, and the procedures of Beckettian fiction generation, begin to become visible. It is a world of confined spaces or else bleak wastes, inhabited by asocial and indeed misanthropic monologuers helpless to terminate their monologue, tramps with failing bodies and never-sleeping minds condemned to a purgatorial treadmill on which they rehearse again and again the great themes of Western philosophy; and all of it will be presented in the distinctive prose that Beckett, using French models in the main, although with Jonathan Swift whispering ghostly in his ear, was in the process of perfecting for himself, lyrical and mordant in equal measures.

In Texts for Nothing (the French title Textes pour rien alludes to the orchestral conductor's initial beat over silence) we see Beckett trying to work himself out of the corner in which he had painted himself in The Unnamable: if "The Unnamable" is the verbal sign for whatever is left once every mark of identity has been stripped from a series of antecedent monologuers (Molloy, Malone, Mahood, Worm, and the rest of them), who/what comes when the Unnamable is stripped too, and who after that successor, and so forth; and - more important - does the fiction itself not degenerate into an increasingly mechanical stripping process?

The problem of how to concoct some verbal formula that will pin down and annihilate the unnamable residue of the self and thus at last achieve silence is formulated in the sixth of the Texts. By the eleventh text, that quest for finality - hopeless, as we know and Beckett knows - is in the process of being absorbed into a kind of verbal music, and the fierce comic anguish that accompanied it is in the process of being aestheticized too. Such is the solution that Beckett seems to arrive at, a makeshift solution if ever there was one, to the question of what to do next.

The next three decades will see Beckett, in his prose fictions, unable to move on - stalled, in fact, on the very question of what it means to move on, why one should move on, who it is that should do the moving on. A dribble of publications continues: brief quasi-musical compositions whose elements are phrases and sentences. Ping (1966) and Lessness (1969) - texts build up from repertoires of set phrases by combinatorial methods - represent the extreme of this tendency. Their music happens to be harsh; but as the fourth of the Fizzles of 1975 proves, Beckett's compositions can also be of haunting verbal beauty.

The narrative premise of The Unnamable, and of How It Is (1961), is held on to in these short fictions: a creature constituted of a voice attached, for reasons unknown, to some kind of body enclosed in a sapce more or less reminiscent of Dante's Hell, is condemned for a certain length of time to speak, to try to make sense of things. It is a situation well described by Heidegger's term Geworfenheit: being thrown without explanation into an existence governed by obscure rules. The Unnamable was sustained by its dark comic energy. But by the late 1960s that comic energy, with its power to surprise, had reduced itself to a relentless, arid self-laceration. The Last Ones (1970) is hell to read was perhaps hell to write, too.

Then, with Company (1980) Ill Seen Ill Said (1981), and Worstward Ho (1983), we emerge miraculously into clearer water. The prose is suddenly more expansive, even, by Beckettian standards, genial. Whereas in the preceding fictions the interrogation of the trapped, geworfen self has had a mechanical quality, as though it were accepted from the beginning that the questioning was futile, there is in these late pieces as sense that individual existence is a genuine mystery worth exploring.

The quality of thought and of language remains as philosophically scrupulous as ever, but there is a new element of the personal, even the autobiographical: the memoirs that float into the mind of the speaker clearly come from the early childhood of Beckett himself, and these are treated with a certain wonder and tenderness even though - like images from early silent film - they flicker and vanish on the screen of the inner eye. The key Beckettian word on, which had earlier had a quality of grinding hopelessness to it ("I can't go on, I'll go on") begins to take o0n a new meaning: the meaning, if not of hope, then at least of courage.

The spirit of these last writings, optimistic yet humorously skeptical about what can be achieved, is well captured in a 1983 letter of Beckett's: "The long crooked straight is laborious but not without excitement. While still 'young' I began to seek consolation in the thought that then if ever, i.e. now, the true words at last, from the minds in ruins. To this illusion I continue to cling."

The above excerpt is from Coetzee's introduction to Samuel Beckett: Poems - Short Fiction - Criticism. You can purchase that volume, which is released in paperback on January 1, 2010, here.

"Wild is the Wind" - Cat Power (mp3)

"I Found A Reason" - Cat Power (mp3)

"Naked If I Want To" - Cat Power (mp3)

"Red Apples" - Cat Power (mp3)

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  1 Reference |

1 Reference |  j.m coetzee,

j.m coetzee,  samuel beckett

samuel beckett

Reader Comments (1)

Good article! I really enjoyed this article. I am always trying to foster good relationships with people who can help my cause. This really breaks it down to a step by step process which is good.Manolo Blahnik replica