FILM

FILM « In Which We Think About It Every Night And Day »

Sunday, May 3, 2009 at 11:40AM

Sunday, May 3, 2009 at 11:40AM

This Man-Boy Flies

by CHAD PERMAN

How I yearn to throw myself into endless space and float above the awful abyss.

— Johann Wolfgang Goethe

It begins inside a mostly barren Astrodome, the one-time Wicked Witch of the West (literally) leading the red and white uniformed African-American marching band she has hired through an out-of-tune rendition of the national anthem.

(They will soon revolt and launch into "Lift Every Voice and Sing", long considered "The Black National Anthem").

Elsewhere in the dome — in a forgotten bomb shelter buried deep within its bowels to be exact — lives an awkward, lonely teenage boy with big glasses named Brewster McCloud who is building the wings he hopes will one day enable him to fly far away from the worries of this world.

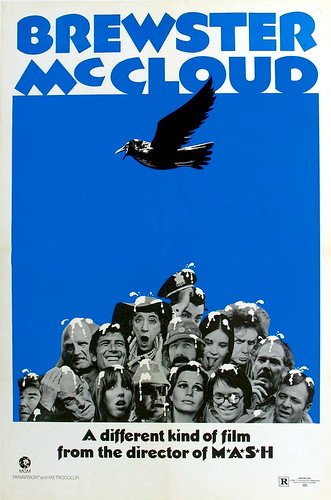

It was 1970 and Robert Altman, armed with the ability to do whatever the hell he wanted to do next in the wake of M*A*S*H's massive success, reared back and swung for the fences. The result is a comic fable of sorts, a parabolic meditation on birds, flight, adolescense, innocence, Icarus, love, temptation, sex, dreams, guardian angels, detectives, serial killers, the impossibility of freedom, and guano.

From the very opening (and then, re-opening) credits, Brewster McCloud feels like a film sent down from another dimension: a ridiculous, anarchic, funny, bizarre, oddly beautiful character piece that seems entirely unconcerned about whatever you might think of it.

Even in a filmography as eccentric and diverse as that of Robert Altman's, Brewster stands out as an insane film, the sort of thing you almost can't believe you just saw. Not for nothing, it was also Altman's own personal favorite of his films.

Bud Cort plays the titular character, a man-boy perched somewhere between Harry Potter and Waldo, whose dreams of flying fuel the narrative thrust of the film.

He hunkers down in the Astrodome and works endlessly on his wings, often under the watchful, protective eye of Louise (Sally Kellerman), who may or may not be his mother — and is later revealed to be a fallen angel herself by virtue of the wing-shaped scars we see across her bare back.

Louise believes Brewster can one day fly, but only if he follows one certain condition: he can never have sex.

If he loses his virginity, she will no longer be able to offer him her protection — a protection that just might have something to do with the recent deaths of people in Brewster's life who have treated him poorly (their deaths continually foreshadowed by being shit upon by birds). Obviously, psychoanalysts would have a field day with this one.

Brewster, though, is human and horny and ultimately unable to resist the temptations of an Astrodome tour guide named Suzanne (Shelley Duvall, in her very first film), and thus begins his tragic downfall, which ultimately concludes in an Icarus-like warning about flying too close to the sun (or in this case, the roof of the Astrodome), before giving way to a surrealistic, Fellini-esque parade of a final scene.

To some extent, Brewster plays out like a stream-of-consciousness ramble of a film, and that's certainly no accident: Altman reportedly disliked the original script so much that he tossed it aside completely and, rather than hire another screenwriter, decided to improvise a great deal of the film on the spot — a style of shooting he would frequently return to throughout the remainder of his career.

Chocked full of ornithological information provided by way of the professor (Rene Auberjonois) who serves as the film's interstitial (and increasingly bizarre) narrator, the film is able to soar to great absurdist heights in some moments, while seemingly teetering on the very brink of complete disaster at others. It's Altman's directorial hand, finally, that keeps the whole thing from coming apart entirely, and you can sense all the fun that he's having behind the camera while doing so.

And so, while Brewster McCloud never emerges as a truly great film, it is also never anything less than an entertaining one. It's also an important film in terms of Altman's own development, expanding on many of the themes and techniques (overlapping dialogue, crowded scenes, improvisation, parallel editing, zoom focus) he had first begun to seriously play with on MASH and would continue to develop and refine throughout his remarkable string of 1970s films, culminating in the crown-jewel masterpiece that was Nashville. As such, it's an vital if often overlooked film in Altman's oeuvre, as well as a strange and wonderful document of a time in American cinema where serious directors — under the guise of being auteurs — were allowed to make things this outrageous and ridiculous with the full support and bankroll of big Hollywood studios.

Chad Perman is a writer and a psychotherapist living in Seattle.

"No Love Today" — Michelle Phillips (mp3)

"It's Getting Better" — Cass Elliot (mp3)

"I Call Your Name" — The Mamas and the Papas (mp3)

"Blueberries for Breakfast" — The Mamas and the Papas (mp3)

"California Dreamin' (live at Monterey)" — The Mamas and the Papas (mp3)

astrodome,

astrodome,  robert altman

robert altman

Reader Comments