FILM

FILM « In Which We Preemptively Acknowledge Our Flaws »

Sunday, January 10, 2010 at 11:19AM

Sunday, January 10, 2010 at 11:19AM

The Impulse To Expiate

by EMILY GOULD

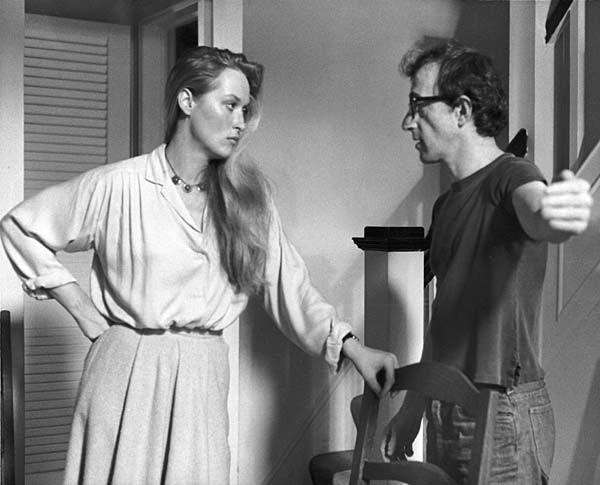

Woody and Diane Keaton meet, in Manhattan, and immediately start contradicting and one-upping each other. They do so intensely, with a focus that excludes the people they’re notionally on dates with. Watching them, you might find yourself suddenly seized with a strange and increasingly less-shakeable suspicion. You, too, have some habitual patterns of interacting with the romanceable people you meet, you've noticed. But have these habits developed organically, or are they just a set of tricks and tics that you subliminally learned from watching early Woody Allen movies? Do these movies succeed, as you’d assumed they did, by evoking the shock of recognition, or is the shock of recognition you feel, watching them, just the end product of a feedback loop?

Regardless, the depth of identification you (fine okay I) feel watching jerks fall in love can be so intense it’s jarring. And when those love affairs fail to end happily — and no matter how many times you’ve seen the movies, those failures somehow have the power to surprise again and again — it is possible to become super bummed out.

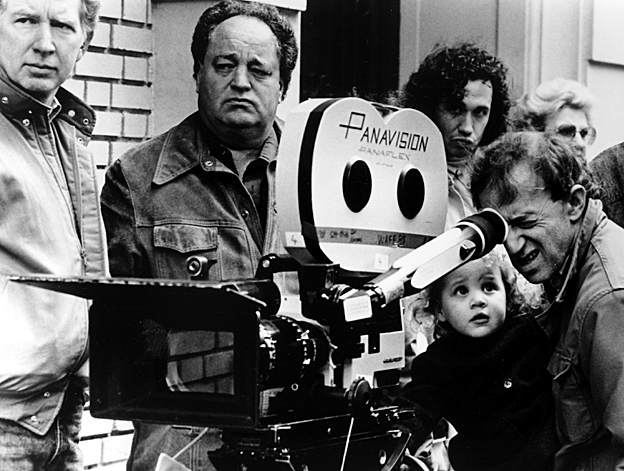

Manhattan is also a bummer because, while it is formally the best Woody Allen movie — the Woody-Allen-movie-est Woody Allen movie — it also codifies the fatal Woody flaw, which is his un-get-aroundably creepy thing for little girls.

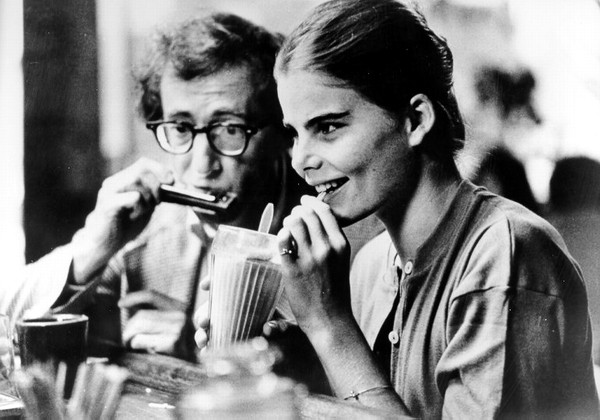

Mariel Hemingway got an Oscar nomination for her performance as Woody’s Dalton-senior love interest in this movie, but the prize seems inadequate compensation for the then-16 year old's having been subjected to multiple takes of the scenes wherein the fortyish Woody gropes and kisses her. Her fundamental physical indifference, even as she mouths lines like "Let’s fool around!", is legible in every line of her coltish body.

The ick factor is especially pronounced when these scenes are juxtaposed with the ones that showcase Diane and Woody’s unfakeable chemistry. But we do believe that Mariel’s Tracy thinks she loves Woody’s Isaac, and that consequently he is able to hurt her. Their love scenes may be stomach-turning, but when he dumps her, Tracy’s obvious pain reveals Isaac’s essential sliminess with unprecedented vividness. "Why should I feel guilty about this? This is ridiculous!” he says, as her beautiful, reason-to-live face quivers on the verge of eerily childish tears. The chord of recognition is struck here too — we have all tried to break a heart guiltlessly, or witnessed someone try guiltlessly to break ours. (But did these movies teach us, and them, how to go about it?)

Tracy, we’re told, is mature for her age. That’s why Isaac is attracted to her, he says early on. But somehow the moments that are meant to demonstrate this maturity are the moments when his real desires slip out – part of his character’s charm, of course, is that he is always helplessly showing his hand. "You keep stating it like it’s to my advantage, when it’s you that wants to get out," she says when he explains why they should break up. "Don’t be so smart, don’t be so precocious," he commands. In their final scene together, when she refuses to buy the recantation of this breakup speech, he tells her not to be so mature.

Isaac's romance with Diane Keaton's Mary Wilkie has its creepy moments too. There is one moment especially when Mary is talking to Isaac but really she is talking to herself, about how she deserves better than Yale, Isaac's married friend who she’s seeing. She is giving herself a little self-esteem lecture about how she is young and beautiful and smart and deserves better. Like Isaac, she is helplessly showing her hand, but unlike him, her foibles aren’t presented lovingly. Isaac’s selfishness seems meant to come off, thanks to his ostentatious self-awareness, as a lovable quirk. Mary seems to have no idea how monstrous she’s being, and therefore seems doubly monstrous.

Isaac’s no monster, though, or at least he isn’t meant to seem like one. His overlay of protective self-awareness — his preemptive acknowledgment of flaws that you haven’t even noticed yet, the sense that he hates himself more than you ever could — has provided a reliable template for future generations of dudes, cinematic and otherwise. It’s this kind of guy who’d think to inoculate himself against charges of misogyny by having Bella Abzug make a cameo in his movie about a forty year old man who’s fucking a high-schooler. These dudes don’t just to get away with being assholes, they want to be loved both for and in spite of it.

You have met these dudes. As kids, they were mocked for the same traits that they’ve now transformed into social currency, but this reversal hasn’t fully salved the wounded rage in them. So they are maybe going to take that anger out on some powerless girls, but they’re going to be so super aware the whole time, of what they’re doing and why. To paraphrase the terrible novel whose opening paragraph Isaac is writing at the movie’s outset, New York is their town, and it always will be. And maybe they live here because the city is like them: trapped between the impulse to expiate or to celebrate its sins, and trapped in the misconception that admitting to them somehow accomplishes both things at once.

Emily Gould is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Brooklyn. She blogs here.You can pre-order her book And the Heart Says...Whatever here.

diane keaton,

diane keaton,  emily gould,

emily gould,  woody allen

woody allen

Reader Comments