ART

ART « In Which Vincent Van Gogh Knows He Is Neurotic And Difficult »

Thursday, October 21, 2010 at 11:32AM

Thursday, October 21, 2010 at 11:32AM

Calm Before the Catastrophe

by W.H. AUDEN

The great masters of letter-writing as an art have probably been more concerned with entertaining their friends than disclosing their innermost thoughts and feelings; their epistolary style is characterized by speed, high spirits, wit, and fantasy. Van Gogh's letters are not art in this sense, but human documents; what makes them great letters is the absolute self-honesty and nobility of the writer.

The nineteenth century created the myth of the Artist as Hero, the man who sacrifices his health and happiness to his art and in compensation claims exemption from all social responsibilities and norms of behavior.

At first sight Van Gogh seems to fit the myth exactly. He dresses and lives like a tramp, he expects to be supported by others, he works at his painting like a fiend, he goes mad. Yet the more one reads these letters, the less like the myth he becomes.

He knows he is neurotic and difficult but he does not regard this as a sign of superiority, but as an illness like heart disease, and hopes that the great painters of the future will be as healthy as the Old Masters.

But this painter who is to come — I can't imagine him living in little cafes, working away with a lot of false teeth, and going to the Zouaves' brothels, as I do.

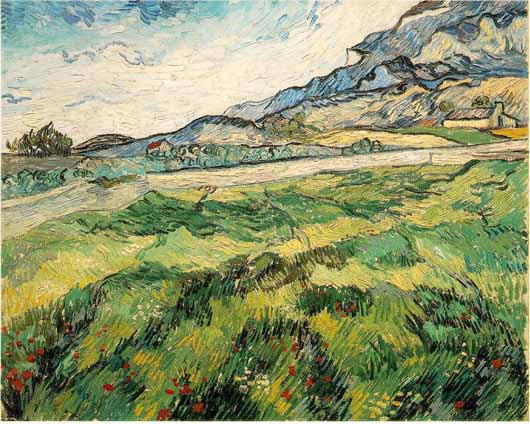

He sees the age in which he is living as one of transition rather than fulfillment, and is extremely modest about his own achievements.

Giotto and Cimabue, as well as Holbein and Van Dyck, lived in an obeliscal, solidly-framed society, architecturally constructed, in which each individual was a stone and all the stones clung together, forming a monumental society.... But, you know, we are in the midst of downright laisser-aller and anarchy. We artists who love order and symmetry isolate oursevles and are working to define only one thing... We can paint an atom of the chaos, a horse, a portrait, your grandmother, apples, a landscape...

We do not feel that we are dying, but we do feel the truth that we are of small account, and that we are paying a hard price to be a link in the chain of artists, in health, in youth, in liberty, none of which we enjoy, any more than the cab-horse that hauls a coachful of people out to enjoy the spring.

Furthermore, though he never wavers in his belief that painting is his vocation, he does not claim that painters are superior to other folk.

It was Richepin who said somewhere,

L'amour de l'art fait perdre l'amour vrai.

I think that is terribly true, but on the other hand real love makes you disgusted with art...

The rather superstitious ideas they have here about painting sometimes depress me more than I can tell you, because basically it is really fairly true that a painter as a man is too absorbed in what his eyes see, and is not sufficiently master of the rest of his life.

It is true that Van Gogh did not earn his living but was supported all his life by his brother who was by no means a rich man. But when one compares his attitude towards money with that of say, Wagner, or Baudelaire, how immeasurably more decent and self-respecting Van Gogh appears.

No artist ever asked less of a patron — a laborer's standard of living and enough over to buy paints and canvases. He even worries about his right to the paints and wonders whether he ought not to stick to the cheaper medium of drawing. When, occasionally, he gets angry with his brother, his complaint is not that Theo is stingy but that he is cold; it is more intimacy he craves for, not more cash.

...against my person, my manners, clothes, world, you, like so many others, seem to think it necessary to raise so many objections — weighty enough and at the same time obviously without redress — that they have caused our personal brotherly intercourse to wither and die off gradually in the course of the years.

This is the dark side of your characters — I think you are mean in this respect — but the bright side is your reliability in money matters.

Ergo conclusion — I acknowledge being under an obligation to you with the greatest pleasure. Only — lacking relations with you, with Teersteg, and with whomever I knew in the past — I want something else....

There are people, as you know, who support painters during the time when they do not yet earn anything. But how often doesn't it happen that it ends miserably, wretchedly for both parties, partly because the protector is annoyed about the money, which is or at least seems quite thrown away, whereas, on the other hand, the painter feels entitled to more confidence, more patience and interest than is given him? But in most cases the misunderstandings arise from carelessness on both sides.

Few painters read books and fewer can express in words what they are up to. Van Gogh is a notable exception: he read voraciously and with understanding, he had considerable literary talent of his own, and he loved to talk about what he was doing and why.

If I understood the meaning of the word literary as a pejorative adjective when applied to painting, those who use it are asserting that the world of pictures and the world of phenomenal nature are totally distinct so that one must never be judged in reference to the other.

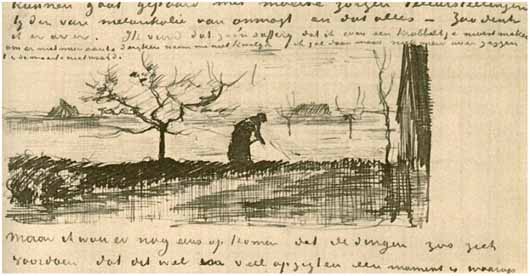

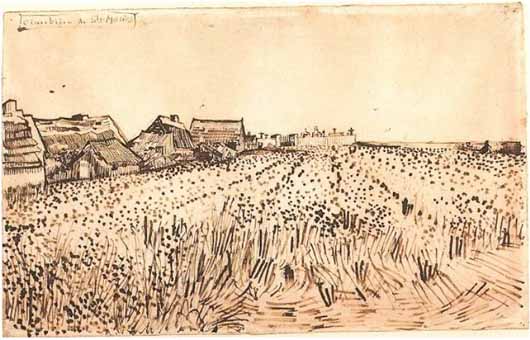

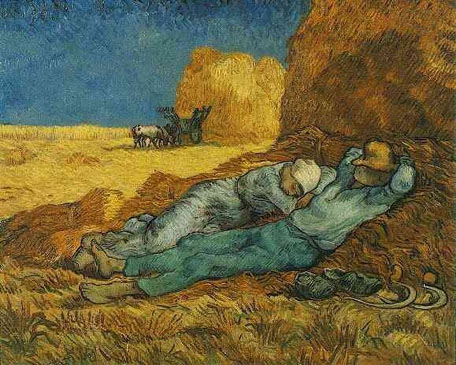

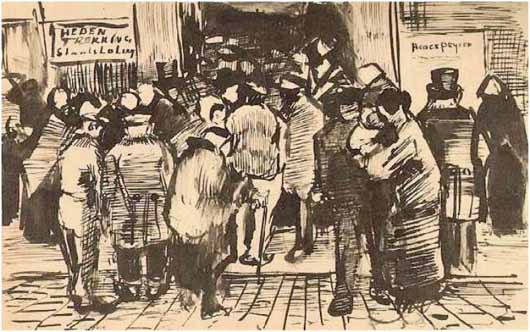

To ask if a picture is "like" any natural object — it makes no difference whether one means a "photographic" or a platonically "real" likeness — or to ask if one "subject" for a picture is humanly more important than another, is irrelevant. The painter creates his own pictorial world and the value of a painting can only be assessed by comparison with other paintings. If that is indeed what critics mean,then Van Gogh must be classified as a literary painter. Like Millet, whom all his life he acknowledged as his master, and like some of his contemporary French novelists, Flaubert, the Goncourts, Zola, he believed that the truly human subject for art in his day was the life of the poor. Hence his quarrel with the art-schools.

As far as I know there isn't a single academy where one learns to draw and paint a digger, a sower, a woman putting the kettle over the fire or a seamstress. But in every city of some importance there is an academy with a choice of models for historical, Arabic, Louis XV, in short, all really nonexistent figures. All academic figures are put together in the same way and, let's say, on ne peut mieux. Irreproachable, faultless. You will guess what I am driving at, they do not reveal anything new. I think that, however correctly academic a figure may be, it will be superfluous, though it were by Ingres himself, when it lacks the essential modern note, the intimate character, the real action. Perhaps you will ask: When will a figure not be superfluous? When the digger digs, when the peasant is a peasant and the peasant woman a peasant woman... I ask you, do you know a single digger, a single sower in the old Dutch school? Did they ever try to paint "a labourer"? Did Velasquez try it in his water-carrier or types from the people? No. The figures in the pictures of the old master do not work.

It was this same moral preference for the naturally real to the ideally beautiful which led him, during his brief stay at an art-school in Antwerp, when he was set to copy a cast of the Venus de Milo, to make alterations in her figure, and roar at the shocked professor: "So you don't know what a young woman is like, God damn you! A woman must have hips and buttocks and a pelvis in which she can hold a child."

Where he differs from most of his French contemporaries is that he never shared their belief that the artist should suppress his own emotions and view his material with clinical detachment. On the contrary, he writes

whoever wants to do figures must first have what is printed on the Christmas number of Punch: "Good Will to all" — and this to a high degree. One must have warm sympathy with human beings, and go on having it, or the drawings will remain cold and insipid. I consider it very necessary for us to watch ourselves and to take care that we do not become disenchanted in this respect.

And how opposed to any doctrine of "pure" art is this remark written only two months before his death.

Instead of grandiose exhibitions, it would have been better to address oneself to the people and work so that each could have in his home some pictures or reproductions which would be lessons, like the work of Millet.

Here he sounds like Tolstoy, just as he sounds like Dostoevsky when he says:

It always strikes me, and it is very peculiar, that whenever we see the image of indescribable and unutterable desolation — of loneliness, poverty and misery, the end and extreme of all things, the thought of God comes into one's mind.

When he talks of the poor, indeed, Van Gogh sounds more honest and natural than either Tolstoy or Dostoevsky. As a physical and intellectual human being Tolstoy was king, a superior person; in addition he was a count, a socially superior person. However hard he tried, he could never think of a peasant as an equal; he could only, partly out of a sense of guilt at his own moral shortcomings, admire him as his superior. Dostoevsky was not an aristocrat and he was ugly, but it was with the criminal poor rather than the poor as such that he felt in sympathy. But Van Gogh preferred the life and company of the poor, not in theory but in fact.

Tolstoy and Dostoevsky were, as writers, successful in their lifetime with the educated; what the peasants thought of them as men we not not know. Van Gogh was not recognized as an artist in his lifetime; on the other hand, we have records of the personal impression he made upon the coal-miners of the Borinage.

People still talk of the miner whom he went to see after the accident in the Marcasse mine. The man was a habitual drinker, "an unbeliever and blasphemer," according to the people who told me the story. When Vincent entered his house to help and comfort him, he was received with a volley of abuse. He was called especially a macheux d'capelots (rosary chewer) as if he had been a Roman Catholic priest. But Van Gogh's evangelical tenderness converted the man.... People still tell how, at the time of the tirage au sort, the drawing of lots for conscription, women begged the holy man to show them a passage in the Holy Scripture which would serve as a talisman for their sons and ensure their drawing a good number and being exempted from service in the barracks... A strike broke out, the mutinous miners would no longer listen to anyone except "l'pasteur Vincent" whom they trusted.

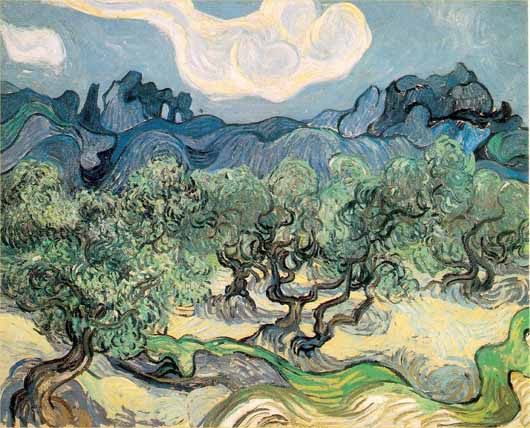

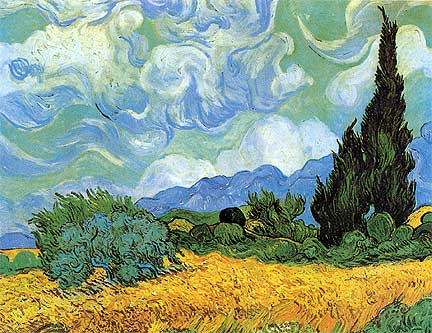

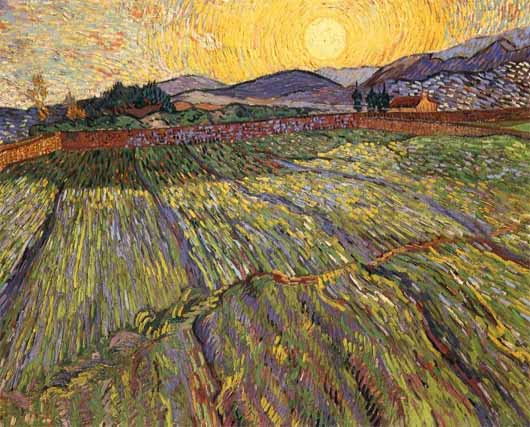

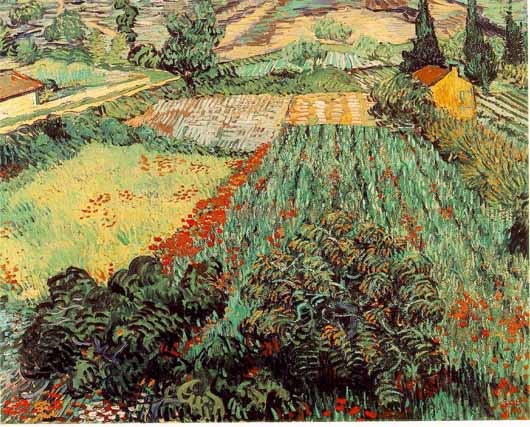

Both as a man and as a painter Van Gogh was passionately Christian in feeling, though, no doubt, a bit heterodox in doctrine. "Resignation," he declared, "is only for those who can be resigned, and religious belief is for those who can believe. My friends, let us love what we love. The man who damn well refuses to love what he loves dooms himself." Perhaps the best label for him as a painter would be Religious Realist. A realist because he attached supreme importance to the incessant study of nature and never composed pictures "out of his head"; religious because he regarded nature as the sacramental visible sign of a spiritual grace which it was his aim as a painter to reveal to others.

"I want," he said once, "to paint men and women with that something of the eternal which the halo used to symbolise, and which we seek to convey by the actual radiance and vibration of our colouring." He is the first painter, so far as I know, to have consciously attempted to produce a painting which should be religious and yet contain no traditional religious iconography, something which one might call "A Parable for the Eye."

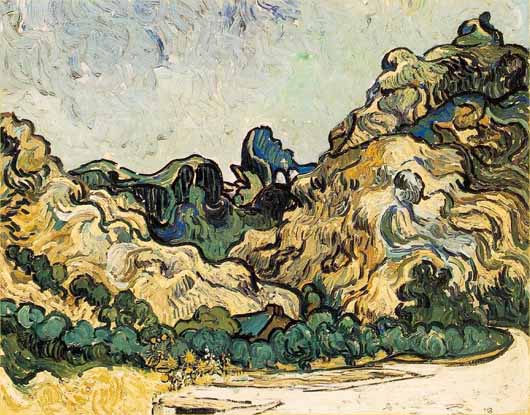

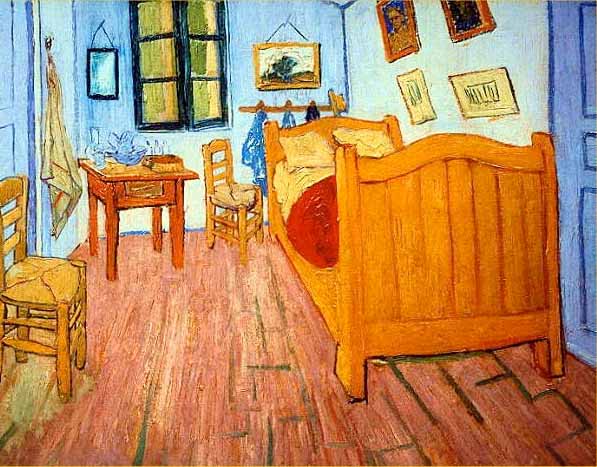

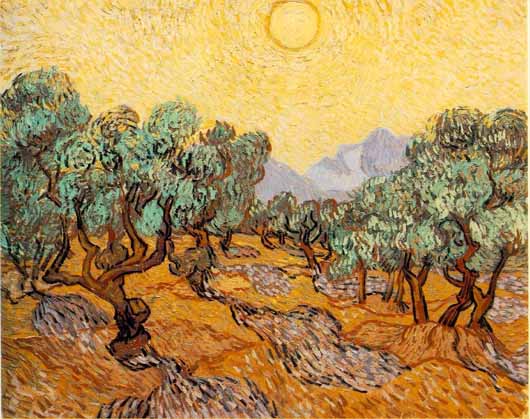

Here is a description of a canvas which is in front of me at the moment. A view of the park of the asylum where I am staying; on the right a grey terrace and a side wall of a house. Some deflowered rose bushes, on the left a stretch of park — red ochre — the soil scorched by the sun, covered with fallen pine needles. This edge of the park is planted with large pine trees, whose trunks and branches are red-ochre, the foliage green gloomed over by an admixture of black. These high trees stand out against the evening sky with violet stripes on a yellow ground, which higher up turns into pink, into green.

A wall — also red-ochre — shuts off the view, and is topped only by a violet and yellow-ochre hill. Now the nearest tree is an enormous trunk, struck by lightning and sawed off. But one side branch shoots up very high and lets fall an avalanche of dark green pine needles. This sombre giant — like a defeated proud man — contrasts, when considered in the nature of a living creature, with the pale smile of a last rose on the fading bush in front of him. Underneath the trees, empty stone benches, sullen box trees; the sky is mirrored — yellow — in a puddle left by the rain. A sunbeam, the last ray of daylight, raises the sombre ochre almost to orange. Here and there small black figures wander among the tree trunks.

You will realise this combination of red-ochre, of green gloomed over by grey, the black streaks surrounding the contours, produces something of the sensation of anguish, called "rouge-noir," from which certain of my companions in misfortune frequently suffer. Moreover, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly green-pink smile of the last flower of autumn serve to confirm this impression.

I am telling you (about this canvas) to remind you that one can try to give an impression of anguish without aiming straight at the historic Garden of Gethsemane.

Evidently, what Van Gogh is trying to do is to substitute for a historic iconography, which has to be learned before it can be recognized, an iconography of color and form relations which reveals itself instantaneously to the senses, and is therefore impossible to misinterpret. The possibility of such an iconography depends on whether or not color-form relations and their impact upon the human mind are governed by universal laws. Van Gogh certainly believed that they were and that, by study, any painter could discover these laws.

The laws of the colours are unutterably beautiful, just because they are not accidental. In the same way that people nowadays no longer believe in a God who capriciously and despotically flies from one thing to another, but begin to feel more respect and admiration for faith in nature — in the same way, and for the same reasons, I think that in art, the old-fashioned idea of innate genius, inspiration, etc., I do not say must be put aside, but thoroughly reconsidered, verified — and greatly modified.

In another letter he gives Fatality as another name for God, and defines Him by the image — "Who is the White Ray of Light, He in Whose eyes even the Black Ray will have no plausible meaning."

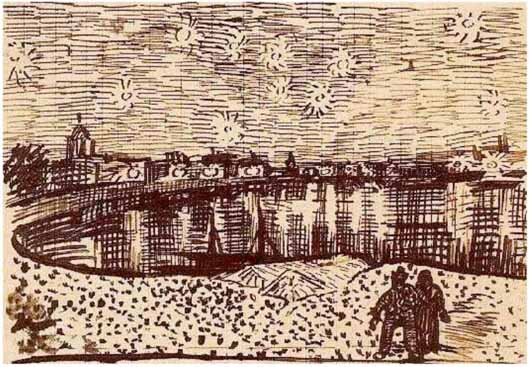

Van Gogh had very little fun, he never knew the satisfaction of good food, glory, or the love of women, and he ended in the bin, but, after reading his correspondence, it is impossible to think of him as the romantic artiste maudit, or even as tragic hero; in spite of everything, the final impression is one of triumph. In his last letter to Theo, found on him after his death, he says, with a grateful satisfaction in which there is no trace of vanity:

I tell you again that I shall always consider you to be something more than a simple dealer in Corots, that through my mediation you have your part in the actual production of some canvases, which will retain their calm even in the catastrophe.

What we mean when we speak of a work of art as "great" has, surely, never been better defined than by the concluding relative clause.

1959

"I Only Know (What I Know Now)" - James Blake (mp3)

"Don't You Think I Do" - James Blake (mp3)

"Tell Her Safe" - James Blake (mp3)

Reader Comments (2)

Swoon. Double swoon. Thank you!

wonderful